May Day, 1968—Battle for Morningside Heights and Teachers College

A Broad Overview of the 1960s Political Landscape

Fueled by heavy consumer demand and the unmitigated expansion of the military-industrial complex, the United States experienced unprecedented economic expansion and hegemony globally, catapulting the US from depression-era isolationism to global super power.

Yet, even as GDP and production raged, far from the sightlines of the 1973 recession, the United States was experiencing not only the growing pains of a maturing nation, but also the societal and economic destabilization at local and national levels.

By the end of 1945, nearly 4 million soldiers had returned home from military service (on an average of 1.2 million per month between September and December) and sought to return to a workforce that was slowly converting back from war time measures to one of industrial production.

The return to the workforce meant a displacement of wartime workers, largely made up of women and, at least in the case of Oakland, a large migratory population from the South. Coupled with the additional pressures brought on by White Flight, the continuation and intensification of Jim Crow laws such as redlining, union exclusion, and intense de facto segregation increased socioeconomic pressures, unevenly, along class and race lines.

Along with the systematic divestment these communities witnessed widespread destruction of affordable housing and business centers. As White’s fled for the suburbs, emerging and traditional Black and minority communities experienced the brunt of the city-planners baton. The baton would soon enough extend to community members, local and national leaders, organizations and institutions.

Testing the Supreme Court decision to desegregate interstate transportation, The Freedom Rides began on May 4, 1961 and were met with significant violent reprisals by white supremacists and police officers that culminated with their bus being bombed in Anniston, Alabama.

Regardless of whether this type of racial terror made the national headlines or simply vanished in the milieu of local politics, these types of violence were consistent and persistent throughout the 1960’s (Klu Klux Klan: A History of Racism and Violence, SPL Center, 2011).

Confronted by the slew of public assassinations of Medgar Evers (1963) John F. Kennedy (1963), Malcolm X (1965) Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr (1968), the 1960s experienced a series of violent upheavals that bore to the surface the severe race and class tensions that the United States was experiencing at a national level.

The assassination of Malcolm X (February 1965), the Watts Rebellion (August, 1965), and the Summer of 1967 were seminal events (amongst many others) that exemplified the complicated inequalities and inequities existing between the lines of the Golden Age of Capitalism in the United States.

While national tensions surged, the deeply unpopular war in Vietnam wedded an overarching Third Worldism movement with emergent radical politics that gave rise to groups including the Black Panthers, American Indian Movement, Brown Berets, and labor movements such as DRUM (Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement). These movements dovetailed with highly active anti-war and the rise of the Free-Speech Movement coming out of Berkeley to combine the predominately white student youth movement with the vanguard of those inter/national organizations mentioned above.

This combination of power movements was by no means monolithic, or always evenly distributed across resources, support, and representation, the resulting alliances—such as The Rainbow Coalition—proved to substantially influence the course of politics in the United States at both national and local levels.

These movements were additionally supported by a web of underground press, newspapers, mimeographs, broadsides and pamphlets that criss-crossed the circuit of universities and factories at prodigious levels well into the 1970s. The underground press kept fellow-travelers connected and informed of movements across the United States, as well as at an international level.

Controversy at Columbia University: 'Gym' Crow and IDA

Perched upon the hill of Harlem/Morningside Heights, Columbia University did not stand immune to the tectonic shifts of its own student youth movements. Two significant grievances provided the foco for actions that took place throughout May. On one hand, students and faculty were troubled by the proposed construction of a new Gymnasium that would segregate entrances for Harlem community via the basement, and limiting access overall to the facilities—and serving Columbia University patrons to the explicit exclusion of Columbia’s graduate and professional schools, Barnard College, or Teacher’s College. The planning and implementation of the gym exacerbated racial tensions that had long simmered between the residents of Harlem and Morningside Heights and the University and effectively merged the Students for a Democratic Society (Columbia University) with elements of Student Afro-American Society (SAS).

Students were also increasingly critical of the university's association with the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA). As an "an independent organization founded in 1956 to conduct weapons evaluation and other research for the Department of Defense "the IDA addresses national security issues that require technical or scientific expertise'. The level of involvement that IDA and Columbia University has always been highly contested and dependent on which side the argument was coming from—conservative elements tended to negate the involvement, while more radical elements tended to maximize it. In The Battle for Morningside Heights: Why Students Rebel, Roger Kahn demonstrates that the level of involvement is more contingent on which side of the line in the sand you occupy as opposed to the numbers in the ledger.

These two major grievances, along with a continued presence of the ROTC program, CIA recruiters, and the crackdown on non-violent protest on campus all led to a rash of violent clashes with police, attempted kidnappings, occupations, teach-ins, and student/faculty strikes.

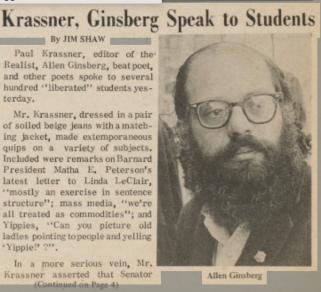

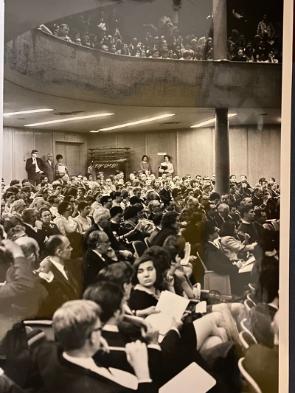

There was a heavy NYPD police presence that garnered national attention due to the particular brutality that took place, but the events of May also found support from major counter-culture icons including the likes of Allen Ginsberg and Paul Krassner.

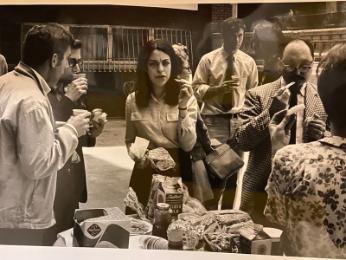

The archive of Columbia University's paper, The Spectator, documents the events of May 1968, starting with their May 1st issue, including the two photos featured here.

Teachers College: Staying the Course

Teachers College participated both in strikes and counter strikes, calling for teach-ins, and faculty-wide discussions regarding the state of the College. Many of Teachers College most illustrious faculty participated including Maxine Greene (below) and Margaret Mead.

In response to the early strike actions at Columbia University, Teachers College students established the “TC Strike Committee”.

A letter from the Committee dated May 7th, 1968 and signed by King Collins, Sue Kanor, Doug Piscitelli, and John Van de Graaff details the desire to:

“stimulate debate and action on the issuesgrowing out of Columbias’ present crisis. We feel that Teachers College, as an institution wholly devoted to the study and practice of education, must concern itself with these issues: both by attempting to work out solutions to some of the problem which beset Columbia, and by proposing reforms to deal with the difficulties at Teachers College, many of which have become evident only in the last few days” (Record Group 24, Office of Student Affairs, Folder 1).

The committee further calls for a suspension of regular classes and the implementation of two new types of classes that aim to critically assess and react to the “Columbia Crisis”. These classes would offer an alternative to “business as usual” courses, in the twofold form of “Liberated Classes” and “Strike-respecting Classes” (ibid).

The former would allow any faculty member or student to establish and conduct new classes or seminars without limitation as to subject matter or restricted attendance, and embrace originality and a sense of provocation. The latter refers to pre-existing courses that have been “fundamentally altered” by consensus between instructors and students. These alterations could include a change in grading structures, meetings place or time, and a change in content or teaching styles.

By May 24th, 1968 the Teachers College Strike Committee released a memorandum titled “Challenge to Recent Administration Propaganda” in support of the student action that occurred on May 21st on Columbia University campus, and indicting the administration as unfairly dismissing their own role in the violent actions two days prior.

The onset of Summer witnessesed further radicalization as the committee formalizes its role as the Radical Action Cooperative. The RAC was based out of 112 Main Hall and offered students a conduit to commit their grievances in a more formal method as illustrated by the publication of TC Gripes. The new letter was composed of issues ranging from better salaries for secretaries and staff, cost per credit, to the need for more water fountains and air conditioning in more rooms, to changing classes to a pass/fail evaluation system.

In true TC spirit, the RAC laid out how TC Gripes presented a more democratic decision-making process as opposed to the linear and autocratic methods that had dictated student policy and criticisms in the past:

[I]n a relatively short period of time, T.C. GRIPES blossomed into a genuine discussion of issues of concern to a large number of people at TC…While the RAC had started out occupying a central position in the matrix of communication, over time the uniqueness of the RAC’s position was. The result is a matrix of free communication in which all individuals have access to all information available to the extent they are interested in it. This is the first step towards participatory democracy (ibid)

In the following edition, various administrative criticisms are addressed, two poem/posters from the Harvard Strike, the phone numbers of Radical and Peace Movements—including the TC Student Senate—are highlighted and the Second Annual Horace Mann Educational Establishment Awards are given out including such honors as "The Ebenezeer Scrooge Extortion Scroll", "The Bourgeoisie Scholar Medallion", amongst many other facetious tributes (see below).

At the Convocation Address of June 1969, Craig Mosher, president of the Student Senate of Teachers College, wasted no time in unpacking the overall state of Teachers College a year later:

"In the Student Senate this year many people have tried hard to change TC. We've sat through countless and sometimes endless committee meetings—having finally been allowed to attend them, thanks to last spring's rebellion...[b]ut this has only been small-scale tinkering with the machinery. Basically, the way in which we teach and learn has not changed".

Throughout his speech, Mr. Mosher takes an emboldened stance, naming names, taking to task issues of curriculum, offering portents and omens, and generally harnessing the timbre of the times. The first half of his speech may be read below.

While the specific demands of the students, faculty, and staff of Teachers College did not garner the same publicity as those of Columbia University—which were reported at the national level, via the press, books, and exhibitions—as researchers we can utilize portions of the archive available to piece together the grievances and compare further administrative records as to their respective impact and outcomes.

We see evidence within TC grievences of the time that reflect the broader inter/national issues of the day that sponsored national organizations and movements slowly drill down to very specific, almost individual, demands by the time the May of '68 strike reaches across 120th street. While the SDS/SAS were clashing with police forces across the street, Teachers College students and faculty were arguing for better curriculums, return to hands on learning, flexibility in attendance, bold measures of innovation and some sense of value for the individual over the machinations of the administration.

Additional Resources

Below are additional photographs from our own Public Relations Files on the flurry of May, Craig Mosher's Convocation Speech, additional pages of the first issue of PROBE, as well as resources available to students for further reading available via Gottesman Library resources

Maxine Greene at Horace Mann Teach-In. Open Meeting Faculty and Staff

Strike Committee

PROBE

Craig Mosher's Convocation Speech

Links in post

from A Broad Overview of the 1960s Political Landscape

Malcolm X: From Political Eschatology to Religious Revolutionary

Article The U.S. 1968: Third-Worldism, Feminisms, and Liberalism

Article The Urban Geography of Red Power: The American Indian Movement in Minneapolis-Saint Paul, 1968-70

The Free Speech Movement: Reflections on Berkeley in the 1960s

My Odyssey through the underground press

from Controversy at Columbia University

Harlem vs. Columbia University Black student power in the late 1960s

The battle for Morningside Heights ; why students rebel

Teachers College: Staying the Course

The San Francisco Mime Troupe: Revising revolution

Primary Source Material from The Office of Student Affairs Collection

Additional Readings

Race Capital? : Harlem as Setting and Symbol

Harlem vs. Columbia University Black student power in the late 1960s

Visualizing a Black Future: Emory Douglas and the Black PantherParty

Harlem : the making of a ghetto : Negro New York, 1890-1930

Music and the Elusive Revolution: Culture Politics and Political Culture in France, 1968-1981

Article "This is Harlem Heights": Black Student Power and The 1968 Columbia University Rebellion