A Brief Introduction to Hazel Hertzberg and a Proposed Framework for Evaluating Indigenous Resources at Teachers College

Research topics may be forged under laser-focused methodologies, linear and straightforward in their understanding, outline, and dissemination. At other times, they may proceed from that of the serendipitous discovery, locating a book next to a book, a phrase within a phrase, a single piece of textual evidence in an unassuming, yet vital locale. Still, at other time, the topics may emerge spontaneous, subtle or explosive, emerging from no place in particular, and yet everywhere at once.

These spontaneous uprising, these ur-events, rising from a seemingly innocuous revelatory moment can often work in wonderful and fertile ways, blending deep-seated and nascent—perhaps even subconscious—ideas and knowledge—and provide the right park for a unique, if not vertiginous, exploration.

In this spirit, I found myself wandering the Special Collection Stacks. Notepad in hand, a list of books in mind: The Earthly Paradise, The Myths of Plato, La Mythologie du Rhin, The Age of Fable, Indian Why Stories, and The Great Tree and the Longhouse. The initial outline was to detail the varied holdings pertaining to mythology, how scholars— from Plato to Walter Benjamin to Horkheimer and Adorno — have utilized mythology in a variety of critical lenses, and how the documents of a library constitute a certain mythology in and of themselves.

And yet, I was sidelined by a single note of warning. A warning that provided both a spark and asubtle grounding for a much different, and perhaps wildly varied thread. Still engaging fundamentally in myth and cosmology, the focus narrowed towards an introductory incursion into indigenous origin stories as evaluated via a teaching paradigm proposed by Hazel Hertzberg, former (and esteemed) Professor of History and Education at Teachers College, as well as an eminent scholar of American Indian History.

“Knowledge Endures//But Books May Not”

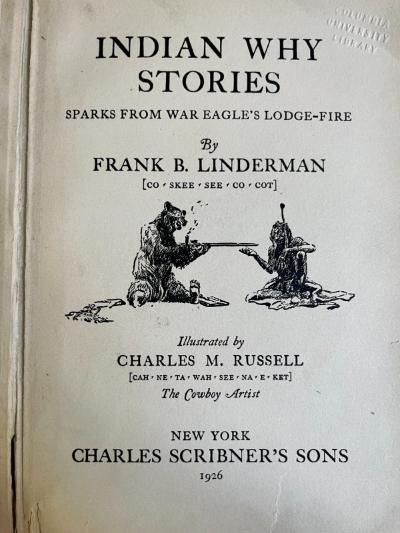

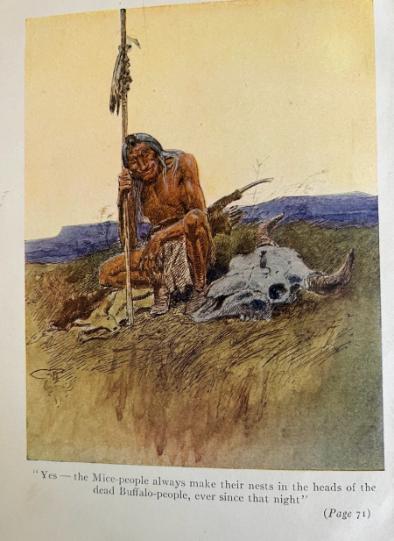

The warning—an often necessary notice with books and material of certain age and conditions—is glued to author Frank B. Linderman and illustrator Charles B. Russell’s book Indian Why Stories: Sparks From War Eagles Lodge Fires. Written in 1926, the book has an incredibly brief introduction, nearly as inane as it is insipid in its regard for the origin stories held within.

The stories within detail the creation history closely associated with the oral traditions of the Blackfeet, Chippewa (Ojibwe), and Cree Tribes. The warning label, though benign in relation to the content, offered an interesting counterpoint to the oral history within by unwittingly prioritizing the written form over the traditional mode of these stories—the phrase of the label inverting—and perhaps subverting— the importance of the creation myths in their orality and the communicative/educational traditions of Plains Tribes.

The label itself, unintentionally, reinforces the dominate paradigm regarding the "Indian Problem", a paradigm that refocuses the cosmological foundation and explanation instead, centering the origin stories (and the orality) as some sort of parenthetical anthropological endeavor. By 1915 (the year of the first edition of this book), the White Man’s conquest East to West has largely subdued and constrained the physical location of a many previously powerful tribes and is now focused on not only marginalizing, but is caught—almost mid-sentence—in a destitute act that is simultaneously erasure and exploitation.

These origin stories are transposed from their orality into the written form, without regard for the ritual practice associated with the (re)telling of these stories. The White Man’s Manifest Destiny looking beyond land, and towards the soul/spirit of the Indians themselves, using Richard H. Pratt’s, founder and superintendent of the (infamous) Carlisle School, dictum of “kill the Indian and save the man”, while also looking to highlight the very culture it seeks to annihilate. This pedagogy of social and cultural assimilation effectively attempted to silence and expropriate what remaining autonomy the indigenous had, by removing (and coopting for entertainment) elements of their traditional culture.

I

Dr. Hertzberg spent considerable effort during her life in developing comprehensive teaching plans in modern teaching institutions. “Issues in Teaching About American Indians” encompasses a general curriculum approach dedicated to prioritizing the defangment of inconsistent stereotypes, providing instead a nuanced engagement of the Native American history that brings “our attention to the historic and contemporary cultural diversity in Indian life…reminding us that the Indian present is a product of a changing Indian past”.

In countering Pratt’s deplorable statement regarding the education of American Indians, Hazel Hertzberg offers corrective advice in a letter written to Social Education editors, regarding the article “Teaching about American Indians” (May, 1972), Hertzberg writes:

…essential towards learning more about human beings whose different cultural ways

were raped and nearly destroyed by intolerable alien invaders. The only disappointment

to me is the silence of the Native American’s voice. Allowing students to hear about

Indian life and outlook and white ways through Indians’ words would help the learner

to gain a true feeling for the Native American’s heart and mind. This drawback can be

easily overcome with an increase of American Indian poetry, speeches and various

accounts now appearing in greater quantities…[1]

In 1978, Hertzberg goes on to map a comprehensive proposal for “Proposal for a Program in Indian History and Education Since 1880”, identifying three specific educational epochs in indigenous education: 1) Government boarding and day schools of the Assimilation Era created in the wake of the 1887 Dawes Act; 2) the Reform Era with a newly rebranded Bureau of Indian Affairs née Office of Indian Affairs with progressive educators and activists readdressing curriculums and pedagogies; 3) the Era of Self-Determinacy where there is the emergence of local school control, Indigenous-run community colleges, and notable matriculation of Native Americans into higher-ed—having ostensibly grown from of the Reform/Activist Era. She is quick to note, however, that none of the “four leading graduate schools of education (Harvard, Chicago, Stanford, TC) have an Indian Program”[2], though the resources are available for student specialization in a number of areas.

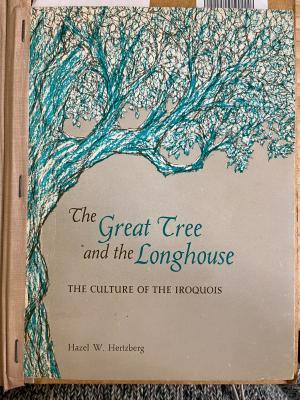

During her teaching and research career, Hertzberg also wrote several books, many (if not all) of which are available through EDUCAT+ here at Teachers College. One book, The Great Tree and the Longhouse, unintentionally presents itself as an excellent foil to Indian Why Stories: Sparks From War Eagles Lodge Fires, from above.

Linderman eagerly promotes the “noble savage” trope, “the lover of nature and close observer of her many moods” (Indian Why Stories: Sparks From War Eagles Lodge Fires, viii), infantilizes the Creation Mythologies of the Plains tribes as a series of mere folk stories and fairy tales (ibid, vii), ultimately leaving no contextualization. While Linderman and Russell do offer their own Indian names (Co’Skee’See’Co’Cot and Cah’Ne’Ta’Wah’See’Na’E’Ket—The Indian’s Friend and The Cowboy Artist, respectively), this seems more of an appeal to authority, as no methodology, bibliography, or record of participants otherwise exist.

Hertzberg, on the other hand, takes a detailed reformed approach, acknowledging and interweaving the historical, cultural, and social relationships that led to the development of the Iroquois’ cosmology, mythology, and material understanding of their world, region, and clans. Throughout the introduction, Hertzberg is careful to point out that the value system, whether spiritual or material, of the Iroquois Nation—as a sort of synecdochic representation—was not intersectional with the values of Old-World migrants settling in the Atlantic region.

Among several other examples, the elm tree is used to signify the divergence of cultural values. Hertzberg writes, on page 3:

To us [non-indigenous], the elm tree may mean shade on a hot day, or possibly, a tree which has been

cut down because of elm blight. It does not have a very important meaning to our

culture. If the elm blight should kill all our elms, we would be sorry to see them go, but

we would not be deeply affected. For the Iroquois, an elm blight would have been a

major tragedy. They would have had to find new materials for longhouse and canoe,

and the Great Elm at the earth’s center would no longer be so closely linked with

everyday experience[3]

Leveraging the disappearance of the elm tree in terms of not only a material tragedy, but a spiritual one as well, she extends the comparison by noting

In our culture, gypsum is an important building material, but to the Iroquois, gypsum

was meaningless. It served no purpose for them. The sudden disappearance of gypsum

today would affect some of our most important industries. But gypsum would have

vanished with no effect whatsoever on the Iroquois world[4]

Using gypsum as an example in this case also offers a very pointed distinction in how “our culture” and the Iroquois culture view their relationship with the land. Anyone who has lived west of the Mississippi or in Upstate New York has likely seen a gypsum mine. They are cavernous gashes across the consisting of pit mines that are dug out of the depths of the earth by monstrous earth moving vehicles. The ore is then processed by crushing the material to a fine dust. The remnants of these quarries can also be seen in various locations in New York, often overlapping with traditional Iroquois land.

The extraction of gypsum, as reported by The mining and quarry industry of New York State : report of operations and production during 1909, is an alienating process, for both man and nature, and certainly antithetical to an Iroquois cosmological understanding of creation—as the Great Elm that sits at the center of the Earth provides the Nation with invaluable materials for their daily life—and the infusion of “religious and spiritual meaning “with the land.

Hertzberg does not solely use her scholarship and writing to illustrate the differences found in the cultural milieu—which are often presented as oppositional as they are irreconciled. Before presenting the various and important mythological foundations of the Iroquois, Hertzberg is careful to point out that just as the Iroquois patterned “their space and gave it meaning” (pg. 4) by creating a basic divisions and patterns, so do we

also create patterns which make order out of our physical world…We have

patterned our space into places to work, places to live, places to shop, and

places to play…

and these places, these divisions, “suggests not only a physical place but a way of life different” from the rest.[5] These comparisons and intersections between cultures continue on, informing the relatively similar dialectical relationships involving time, land, and society—both micro and macro.

III

In A desire to see : an analysis of popular reading of college students 1965-1975 (1980)—chaired by Max Wise and Maxine Greene— author Robert R. Lawrence examines the popular reading trends of college age students, both academic and non. One book that catches the eye in the study, as both contemporarily controversial, but interesting in the subtext of cultural reclamation is Carlos Castaneda’s earliest books, The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge (1968).

For those unfamiliar, the book is more fiction than fact, following an intrepid author to th Northern Mexico state of Sonora in search of spiritual guidance with the aid of a Yaqui Indian Sorcerer—don Juan Matus—and the psychedelic assistance of various desert plants including Jimson, Psilocybin Mexicana, and Peyote.

While the book is later proven to be a farcical approach to an anthropological study, Castaneda does offer a glimpse into “truly another world, foreign enough to make us suspend judgement”[6] and in this suspension, Lawrence’s dissertation brings an interesting point to light: that the youth of the 60’s and 70’s was attempting to engage in traditions that ran counter to the traditionally accepted values the White-Anglo Protestant variety.

The popularity of psychedelia and Native traditions reached far ranging audiences involved in varied spirited domains of counter-culture ethos, from radical power groups with actual ties to Native American traditions, such as the American Indian Movement (AIM), to prototypical hippy and the “back to the land movement” communes. In his 1968 dissertation An investigation into the personal characteristics and family backgrounds of psychedelic drug users, James Kleckner notes that there has been a “psychedelic explosion”. In the introduction, he emphasizes:

…the startling spread of psychedelic drug use across American college campuses can

certainly be termed a psychedelic explosion, for few things have proliferated more

rapidly or aroused more concern in recent years than the problem of psychedelic

drug use and the rapid acceptance into popular culture of the psychedelic orientation…

psychedelic drugs have passed from being e esoteric indulgence of an isolated few into the realm of popular culture…[s]o rapidly has the situation developed, that while we have now had psychedelics explored by congressional hearings, network television and radio shows, newspaper features, national magazines, and scientific journals, just three years ago the lay public had never even heard of the word psychedelic…

Kleckner goes on to trace the historical circumstances of his near past that brought together the confluence of historical events that inevitably made the “time clearly right for psychedelics to emerge”. These events, both fluid and discrete, consisted of the tensions created from the polar opposites of pessimism and hope: on the one hand we had the assassination of several young, charismatic leaders, a visceral reaction to a previous generations’ pessimism, and the ever-mounting and unpopular war on the other side of the globe. There were also profoundly intrepid and hopeful ideations and action taking place: the first manned flight to space, landing on the moon, the coalescing of a national and effective Civil Rights Movement, the creation of the Peace Corps (which Teachers College actually helped prototype with our Teachers for East Africa Program), and the solidarity generated around the Anti-War Movement.[7]

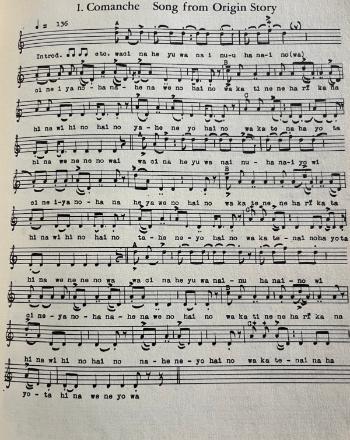

This sort of historical confluence that transformed into a timely necessity was obviously not the sole occasion of such an occurrence—nor was it unique to the pressures experienced to break through the societal fabric of the time. In the 1949 dissertation, Peyote Music, David McAllester details a brief historical sketch of the rise of the “peyote cult” in the United States. The widely accepted date for the establishment of peyote use in a ritualistic manner by American Indians in the United States is around 1870. The date is significant as the final throes of many of the Plains Tribes being moved to reservations in Oklahoma and the surrounding areas. In her seminal work Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History, S.C Gwyne details the rise of Quanah Parker as the spiritual and pragmatic warrior leader during—and after—the transition of the Comanche’s into predominantly reservation life.

The Comanche—and greater Plains Tribes including Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne, Arapaho, Otoe, Southern Utes, and many more—had borne the brunt of the United States’ philosophic ideology of Manifest Destiny, losing their ancestral hunting grounds, the herds of roving buffalo were decimated in mass numbers, their nomadic life of hunting, warring and raiding effectively brought to an end. Quanah Parker, son of a Comanche War Chief Peta Nocona and Cynthia Ann Parker—a Comanche captured Anglo-American—introduced the use of peyote, interweaving Christian and traditional elements of tribal culture, to establish a uniquely Comanche ceremony and culture of ritual which it had, as purely nomadic tribe, yet to establish.

The origin story and creation myth of peyote (pg. 14) of McAllester’s book, is “despite certain supernatural elements, more of an historical account than a myth”. In his view, this

marks a difference from certain other important rituals in the area. The origin myths of the Sun Dance and the Winnebago

Medicine Dance ... both begin with the flood and the creation of the earth and go on to tell how the rituals were given at the

beginning of tribal history and are a necessity for harmonious relations with the universe (pg.17)

The Peyote story, however, begins where the resigned Comanche story left off—with the narrative of a great battle,

the peyote paraphernalia derives from weapons of war: the young Comanche bow has become the brace used by each

singer in turn during the ceremony…the conciliatory content of the peyote philosophy is foreshadowed by the suspension of

the hostilities between the Carrizo Apache and the seven Comanche who arrive as predicted, and our informant assumes

that the prayers which begin the ceremony must include a prayer for peace

The story, while solidly identifiable by typical Plains’ tropes such as initiation, transferring of power, and a supernatural consorting with the dead, lacks certain other traditional thematic elements associated with tribes that were more steeped in ritual content. For instance, there is no mention of a distant past in which events had happened and have since been forgotten, only to be rediscovered via the initiate or ritual, nor is there mention of typical Plains themes (see page 18), and—perhaps most importantly—there is no “transition from the mythological period to the age of modern man and modern ways” (pg. 18).

By very nearly referencing the traditional elements of Plains’ Tribes, but diverging just enough to create an origin noting these absence traits, the Comanche create an effective ritual and spiritual culture that functions as a remarkable palimpsest that simultaneously acknowledges their history with the world around them, yet sets them apart—and perhaps above—from other tribes (and in Comanche Culture would figure into being enemies), while also creating the space necessary to reclaim—primarily from the white man’s campaign of destruction ala Manifest Destiny.

McAllester goes on to establish that the peyote style and ritual is a remarkably unique due to the overall variability of the ritual itself (pg.83)—involving multiple tribes, uncountable clans, across many regions, with uncountable external pressures. This variability, as observed in the study of the structure, accompaniment, text and performance reinforces the palimpsestic approach to the peyote ritual, allowing for other songs, from non-Comanche’s, to be permitted into the ritualistic moments. In some recorded instances, anthropologists were encouraged—or given—traditional Christian hymnals to sing during the ceremony as with Carling Malouf who sang “Onward Christian Soldier” (pg.83).

The flexibility built into the ritual, allowing for the use of adjacent spiritual influences ultimately creates some significant difficulty in marking the lineage and sources of the “Peyote Style”, as McAllester names it. However, in terms of Hertzberg’s process of assimilation, reform and reclamation, we see all three methods at work in a single, substantive instance with the creation of the peyote ritual.

Quanah and his predecessors simultaneously limit the imposing powers of The Great Father by absorbing aspects of those powers which had initially (and indeed in many ways continue to) impoverished the Plains Tribes, trans(re)form those impoverishments and imposed cultural values into identifiable and relatable values, that then allowed for a reclamation of a new origin story for the Plains Tribes at large, and the Comanche in particular.

In a final act of humbleness, and perhaps affirming his outsider-status—and ultimately his inability to come full circle to any singular answer—McAllester acknowledges the fundamentally complex and nuanced nature of the origination of the rituals (pg, 88), leaving the question more broadly open as to the influences and convergences associated with the formation of the Peyote Cult.

As often as we associate—and perhaps privilege— the notion of knowledge, and the transmission of that knowledge with and by textual evidence, we should remain open to the importance that alternative histories provide, understanding that many of these histories have been uniquely marginalized by the same cultures and powers that seek to service them a variety of purposes today—whether for academic, entertainment, or artistic purposes.

Examining Hazel Hertzberg’s “Proposal for a Program in Indian History and Education Since 1880” provides a flexible framework to structure courses and programs around American Indian History, but also articulates a possible and plausible lens with which to evaluate not just material relating to indigenous populations, but perhaps also many populations that have experienced marginalization whether through different types of violence, from genocidal to economic.

While the warning labels we place upon our many objects of affection here in the library are necessary to preserve and steward knowledge to the next generations, and to generations beyond, it is equally hopeful to think that while the book may not endure, knowledge will.

Selected resources on Indigenous and Native Mythology, Culture, and History from the Special Collections:

A tour of observation among Indians and Indian schools : in Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma and KansasSelected writings of Edward Sapir in language, culture and personality

American Indian Bibliography (Hazel Herztberg Papers)

American Indian and Eskimo authors ; a comprehensive bibliography

American primitive music ; with especial attention to the songs of the Ojibways

Catalogue. Carlisle Indian Press

Indian boarding schools : findings of the Meriam report

Myths and tales of the southeastern Indians

The American Indians and their music

The Institute of American Indian Arts : a basic statement of purpose

Twentieth Century American Indian History A Selected List of Primary Sources (Hertzberg)

Footnotes

[1] Social Education-Indian Issue (Reactions), Hazel Hertzberg Collection

[2] Proposal for a Program in Indian History and Education Since 1880

[3] The Great Tree and the Longhouse

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid, page 5.

[6] A desire to see : an analysis of popular reading of college students 1965-1975

[7] An investigation into the personal characteristics and family backgrounds of psychedelic drug users, pg. 4