Accessibility in Libraries

Research Buzz

Here at the Gottesman Libraries, we are committed to making our spaces and services accessible. When making decisions such as whether or not to subscribe to a new database, what colors to use on the website, or where to display signage promoting events, the Libraries stay mindful of accessibility standards, user feedback, and support and accommodations for individuals with disabilities.

BACKGROUND

Accessibility underlies the institution of libraries in America and across the globe.

The American Library Association, the oldest and largest association of libraries in the world, states access as a core value: “All information resources that are provided directly or indirectly by the library, regardless of technology, format, or methods of delivery, should be readily, equally, and equitably accessible to all library users” (ALA, 2019 ALA Policy Manual B.2.1.14 Economic Barriers to Information Access).

Equity of access to all users means that people with varying backgrounds, experiences, and abilities can use library resources and spaces. Eliminating economic barriers to information by providing users access to books for free is the foundation of public libraries in the United States. Access is a critical factor when making all library decisions, from designing library architecture to deciding hours of operation. For instance, libraries ensure that bookshelves aren’t too high so that everyone can reach them. A library’s digital services are subject to the same accessibility evaluation, such as ensuring the digital tools we promote are compatible across operating systems.

Equity of access to individuals with disabilities has always been important to libraries given their mission to adequately serve all their patrons and users. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, libraries were actively incorporating into their services resources geared towards people with disabilities, especially tailoring services to people with vision impairments (American Library Association and Knology, 2022). The Library of Congress opened a reading room for the blind in 1897 (National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled, Library of Congress). Early alternative media formats such as the audiobook’s precursor, the talking book, became available to library patrons across the country in the 1920s. The American Library Association created standards for ensuring access to people with disabilities in 1961, thirty years before the Americans with Disabilities Act was signed into law.

Girl with an early twentieth-century phonograph talking book. Courtesy of American Foundation for the Blind

The Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) has become the foundation for policy and legislation regarding the rights and protections for people with disabilities. A major contribution of the ADA was its definition of disability. Many libraries and institutions draw on the ADA’s definition of disability when creating their accessibility policies. The ADA defines disability as a “person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activity. This includes people who have a record of such an impairment, even if they do not currently have a disability. It also includes individuals who do not have a disability but are regarded as having a disability.”

The term, however, is understood differently within legal, medical, and social frameworks. The social model of disability places it within the greater context of the structural, attitudinal, and environmental barriers that inhibit the inclusion of people with disabilities (French & Swain, 2013). The social understanding of disability is important to libraries since they are institutions deeply embedded in larger social systems.

For more information on how disability has evolved, as well as the complicated and intersectional significance of the term “disability,” see “Ill/Legal: Interrogating the Meaning and Function of the Category of Disability in Antidiscrimination Law, ”(Berg, 1999) and “We Need to Talk About How We Talk About Disability: A Critical Quasi-Systematic Review,” (Gibson et al., 2021).

A contemporary talking book. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

AN OVERVIEW OF CURRENT ACCESSIBILITY IN LIBRARIES

How do libraries ensure accessibility currently? Libraries implement tools, services, and resources as accommodations for people with disabilities. Assistive/adaptive technologies (AT) such as braille materials, large print materials, screen readers, alternative keyboards, reachers/grabbers, wheelchairs, and so on, are important to have and advertise in libraries. For instance, libraries implement live captioning for video resources or Zoom instruction sessions; offer private study rooms and integrate clear signage; and include elevators and accessible bathrooms, to name a few.

Disability Access Symbol. The information symbol indicates the location for specific information or materials concerning access, such as “LARGE PRINT” materials, audio cassette recordings of materials, or sign interpreted tours. Courtesy of Graphic Artists Guild.

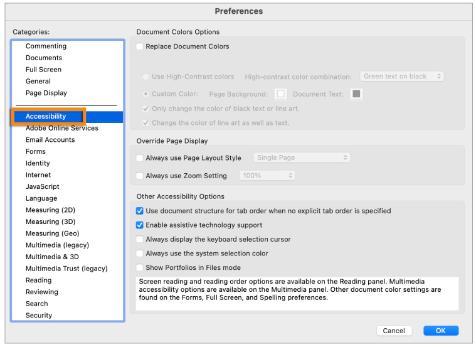

Accessibility in libraries can be seen from various vantage points. In addition to adaptive technology like those listed above, many studies have examined the usability of electronic resources for people with disabilities. Many scholars in library studies have researched the accessibility of PDFs and E-journals. PDFs, the standard for fixed-format document exchange and publishing, are generally considered accessible because they allow for preservation and dissemination. Visually impaired users rely on screen readers to access PDF content. This means that PDFs must be well-structured so that someone can effectively navigate the document via a screen reader. Visual elements within a PDF, such as graphs, illustrations, formulas, and images need alternative text description. One study found that while PDFs generally meet accessibility criteria, many journals fail to provide alternative text for images and lack metadata tags that orient a visually impaired user to the structure of an article (Darvishy, 2018; Nganji, 2015).

Adobe Acrobat PDF Reader accessibility settings. Courtesy of Adobe Inc.

When it comes to the proprietary databases that libraries subscribe to, there are web accessibility guidelines that serve as criteria when evaluating the accessibility of a third-party database. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 and Section 508 ensure that web content can be used by as broad a community as possible. Four categories have been developed to help guide web authors and creators on web accessibility; sites should be “perceivable,” “operable,” “understandable,” and “robust” (W3C, 2018). However, related literature has concluded that these guidelines are often not sufficient or well-enforced (Byerley & Beth Chambers, 2002). One recent study found that many electronic resource databases that were designed to be “user-friendly” were in fact incompatible with assistive technology such as screen readers (Willis & O’Reilly, 2020). Libraries and information centers have made policies and standards to evaluate the e-Learning environments they subscribe to, since ultimately the onus is on the library to ensure accessibility of third party vendors. The Voluntary Product Accessibility Template (VPAT) is a method of conducting an expert review to ensure vendor compliance with usability standards. However, having users with disabilities test the platforms or content using assistive technologies is a critical way to evaluate databases and digital platforms for accessibility, and one that should be prioritized.

Compared to other institutions, libraries have always been at the forefront of accessible web design (Bertot & Jaeger, 2015). With the onset of the COVID-19 epidemic, libraries responded quickly to ensure users had access to robust digital resources and remote services. As the development of online learning objects, such as video tutorials and research guides (most commonly Springshare’s LibGuides platform), grew, so did the need to evaluate these emerging aspects of library services in terms of accessibility criteria. For example, there are best practices when developing slide decks and presentations (Chee et al., 2022). Slide transitions should be user controlled. Numbered lists, as opposed to bulleted lists, should only be used when steps described follow a sequential order. Similarly, research guides should consistently label hyperlinks and maintain standardized presentation for screen reader navigation. Audio/visual materials present challenges to accessibility due to their complexity. Learning objects with meaningful audio must have transcripts that are intuitive to access. Videos must have user-controlled playback options. These considerations are only a small sample of ways learning objects are designed to be accessed by people with disabilities.

DISABILITY JUSTICE - A CRITICAL FRAMEWORK

Disability Justice is a social justice movement that understands disability and ableism as it intersects with other modes of oppression such as race, gender, and class (Piepzna-Samarasinha, 2018). The methods libraries use to uphold accessibility demonstrate how accommodation is built into the functional design of library resources in order to not exclude or discriminate against people with disabilities. While these particular tools are extremely important to ensure equitable access, there is also work being done to shift the conversation away from focusing on meeting the needs of individual impairments and towards how libraries can address and change the social constructs that oppress people for being different (Kumbier & Starkey, 2016).

In “Accessibility for Justice: Accessibility as a Tool for Promoting Justice in Librarianship,” Stephanie Rosen writes, “The Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) was achieved through coalitional activism that reflects the intersectional nature of disability and, because the law prohibits discrimination by design, it demands active design agendas that stand to benefit people with and without disabilities—and marginalized people in particular” (2017). When we design library resources and systems with accessibility in mind, as opposed to retrofitting existing services, we serve a social responsibility of inclusion and access for all. Universal Design, a large component of web accessibility, demonstrates that designing tools from the outset without any potential to exclude people with disabilities is an action towards social justice. Rosen notes how closed captioning in A/V resources not only allow for hearing impaired people to access content, but also people with less fluency in the language. She also notes how wheelchair accessible bathrooms also enhance accessibility for trans and gender-nonconforming people.

At the origin of libraries is the pursuit of equitable access to information. As the world changes, the scope and impact of access has grown to be a collective effort. Enhancing accessibility here at the Gottesman Libraries is a continual process of evaluation, reflection, and education. We connect with our users to understand their needs while anticipating and removing potential barriers to information and services. Please let us know if there are more ways that we can support the community in this respect.

The Office of Access and Services for Individuals with Disabilities (OASID) works with all academic departments, faculty members, and administrative offices in an attempt to ensure that individuals with disabilities can participate fully and equally in the Teachers College community.

Further Reading

Services to People with Disabilities: An Interpretation of the Library Bill of Rights (ALA)

Columbia University Libraries’ Disability Studies Research Guide

Works Cited

American Library Association and Knology. (2022, October 14). ALA and Knology explore disability and accessibility in “Accessibility in Libraries: A Landscape Report” [Text]. News and Press Center. https://doi.org/10/ala-and-knology-explore-disability-and-accessibility-accessibility-libraries

Berg, P. E. (1999). Ill/Legal: Interrogating the Meaning and Function of the Category of Disability in Antidiscrimination Law. Yale Law & Policy Review, 18(1), 1–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40239515

Bertot, J. C., & Jaeger, P. T. (2015). The ADA and inclusion in libraries: Libraries have been and continue to be champions for access. American Libraries. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/blogs/the-scoop/ada-inclusion-in-libraries/

Byerley, S. L., & Beth Chambers, M. (2002). Accessibility and usability of Web‐based library databases for non‐visual users. Library Hi Tech, 20(2), 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378830220432534

Chee, M., Davidian, Z., & Weaver, K. D. (2022). More to Do than Can Ever Be Done: Reconciling Library Online Learning Objects with WCAG 2.1 Standards for Accessibility. Journal of Web Librarianship, 16(2), 87–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2022.2062521

"Core Values of Librarianship", American Library Association, July 26, 2006.

http://www.ala.org/advocacy/advocacy/intfreedom/corevalues (Accessed September 27, 2023)

Darvishy, A. (2018). PDF Accessibility: Tools and Challenges. In K. Miesenberger & G. Kouroupetroglou (Eds.), Computers Helping People with Special Needs (pp. 113–116). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94277-3_20

French, S., & Swain, J. (2013). Chapter 10—Changing relationships for promoting health. In S. B. Porter (Ed.), Tidy’s Physiotherapy (Fifteenth Edition) (pp. 183–205). Churchill Livingstone. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-4344-4.00010-9

Gibson, A., Bowen, K., & Hanson, D. (2021, February 24). We Need to Talk About How We Talk About Disability: A Critical Quasi-systematic Review – In the Library with the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2021/disability/

History. (n.d.). [Webpage]. National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled (NLS) | Library of Congress. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from https://www.loc.gov/nls/about/organization/history/

Kumbier, A., & Starkey, J. (2016). Access Is Not Problem Solving: Disability Justice and Libraries. Library Trends, 64(3), 468–491. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2016.0004

Nganji, J. T. (2018). An assessment of the accessibility of PDF versions of selected journal articles published in a WCAG 2.0 era (2014–2018). Learned Publishing, 31(4), 391–401. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1197

Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. L. (2018). Care work: Dreaming disability justice. Arsenal Pulp Press.

Rosen, S. (2017, November 29). Accessibility for Justice: Accessibility as a Tool for Promoting Justice in Librarianship – In the Library with the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2017/accessibility-for-justice/

The ADA and Inclusion in Libraries. (n.d.). American Libraries Magazine. Retrieved September 27, 2023, from https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/blogs/the-scoop/ada-inclusion-in-libraries/

What is Universal Design | Centre for Excellence in Universal Design. (n.d.). Retrieved September 27, 2023, from https://universaldesign.ie/what-is-universal-design/

Willis, S. K., & O’Reilly, F. (2020). Filling the Gap in Database Usability: Putting Vendor Accessibility Compliance to the Test. Information Technology & Libraries, 39(4), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v39i4.11977