A History of the Special Collections and Archives of Teachers College in Two Parts

Part I: 1887-1961

A History of the Special Collections and Archives of Teachers College, Part I: 1887-1961

Introduction

For the past several months, the Special and Digital Collections Unit has been working to better understand the breadth and depth of our collections. This work has led to multiple ongoing projects: the updating of our intellectual access and description through bibliographic records and finding aids; the mapping of collections; and ongoing preservation and digitization of materials for long-term access and use. As we have examined our accession records and finding aids, as we have drawn connections between our collections, and as we work to preserve materials and make them more accessible, a history of the Special Collections and Teachers College Archives emerged. Unearthing this history has allowed us to trace our collection practices and follow our archival policies across 137 years. This two-part blog post provides as detailed a history of the special collections and archives as our existing records allow.

The Bryson Library

When the New York College for the Training of Teachers was established in the fall of 1887, the College’s library inherited the books, pamphlets, and other educational materials of its predecessor organizations, the Kitchen Garden Association and the Industrial Education Association [1]. The library retained approximately 680 books from the Industrial Education association, and over the course of its first year, acquired nearly 650 more items [2]. At the time, the library occupied one room at 9 University Place, and under the guidance of Mrs. Peter M. Bryson, who endowed the library in the memory of her late husband, the space began to transform [3]. Mrs. Bryson oversaw the hiring of the college’s first professional librarian, Mary Medlicott, who helped organize, catalog, and manage the growing collection until her resignation in 1890 [4].

In the spring of 1890, Lilian Denio succeeded Medlicott as the Librarian of the Bryson Library at the newly established Teachers College. Denio’s experience as a cataloguer made her an excellent candidate for processing and organizing the library’s incoming materials [5].The library’s holdings went from 2,7760 volumes in 1890 to nearly 7,600 by 1896 [6]. The expansion of the library was aided in part by the College’s move to 120th street in 1894, which granted the library much more space for the acquisition of new materials and the development of various collections within the library, including special collections [7].

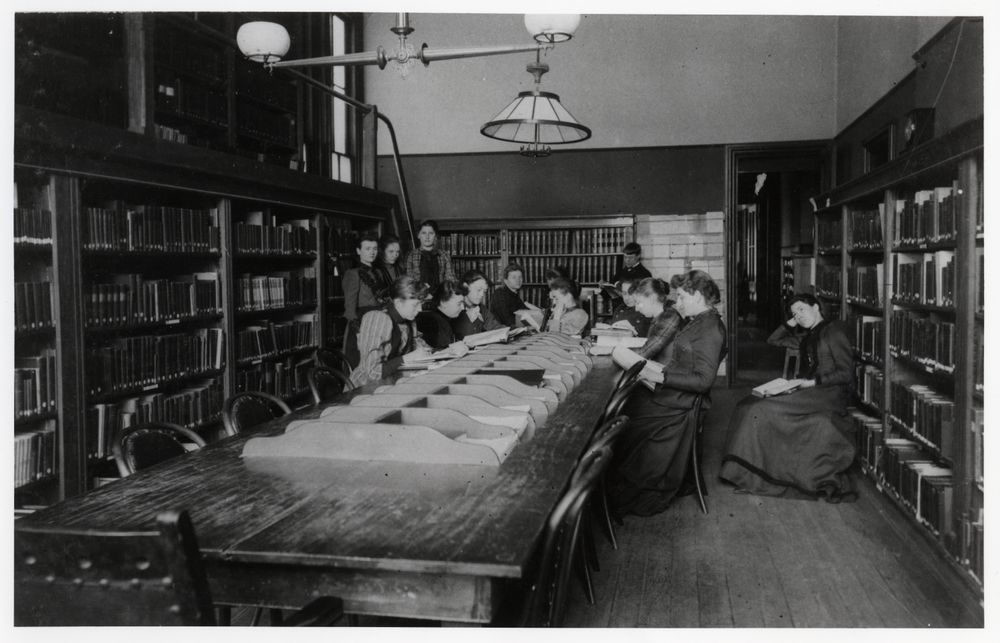

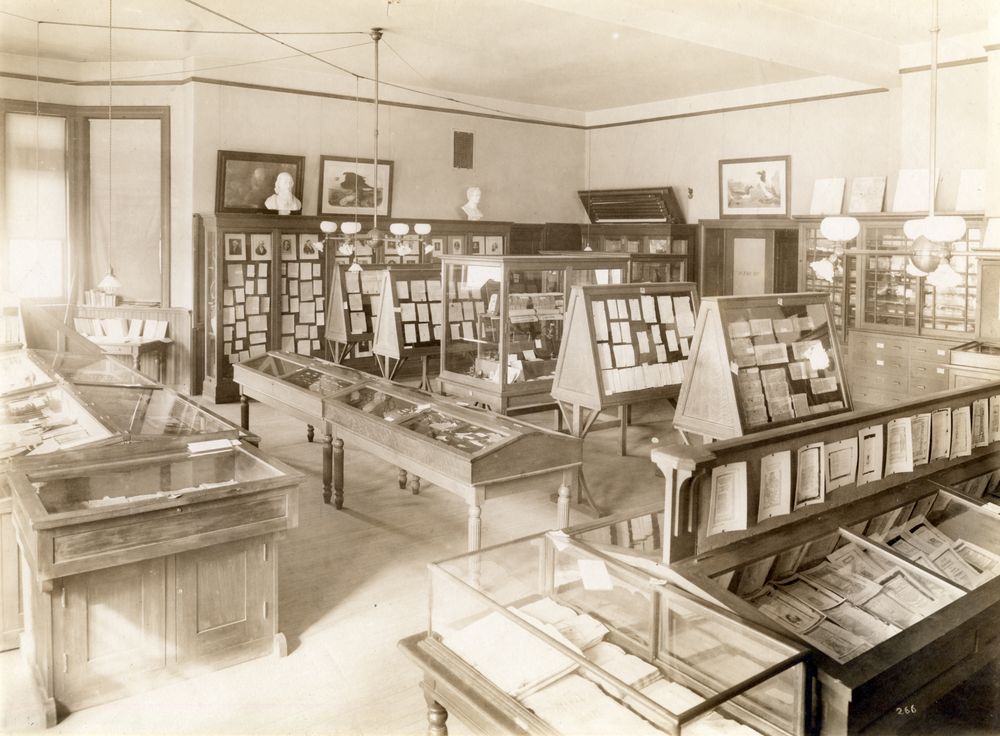

9 University Place, Library, Teachers College. (Date Not Known)

The 1890s saw the beginnings of what we would now recognize as special collections, rare books, manuscripts, and archives. The first mention of the term “special collections”' within the library’s historical records was in an 1892 report authored by Denio. Denio wrote that she oversaw the development of departmental libraries, or what she termed “special collections”[8]. These “special collections” were curated and maintained by their respective departments and consisted of “Books upon Science, Manual Training, Cooking, and Kindergarten,” among other topics [9]. Denio believed that these departmental libraries allowed for more targeted educational opportunities within the college and saw such collections as nexuses between students, faculty, and new ideas [10]. Over the next several years, she collaborated with departments to build up collections with a “foundation in psychology, history, and methods of education” [11], while also liaising with donors and benefactors like Mrs. Bryson to establish new collections within the library.

The departmental libraries continued to grow throughout the 1890s, as did the library’s holdings of rare books and manuscripts. In 1894, Mrs. Bryson established a special collection at Teachers College with a gift of 100 books in “American history, Archaeology and Art” which was called the “Hemenway Collection” in memory of her sister [12]. By February of 1895, the Hemenway Collection had gained another 200 books and the Bryson library received “a collection of autograph letters filed in a handsome leather case; containing letters from Thomas Jefferson, John Hancock, Lafayette, John Adams, Robert Morris, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and others” from Mrs. C.P. Hemenway [13]. Many of these letters still exist today in the Gottesman Libraries’ Education Manuscript Group 1 [ca 1682-1983] Collection. Other donations to the Bryson Library included W.J. Linton’s Masters of Wood Engraving from Mrs. Samuel Putnam Avery in 1895 [14].

The move to 120th street in 1894 saw an increase in donations to the library’s special collections. In 1895, an anonymous donor gifted the works of Cotton Mather to the Bryson Library; trustee V. Everit Macy donated photographs related to geography and history; Mr. W.E. Dodge donated Muybridge’s Animal Locomotion; J.D. Fish gifted bound volumes of Gentleman's Magazine; and Grace Dodge gifted the library with publications from the New York Historical Society [15]. By the end of Lilian Denio’s tenure at Teachers College in 1896, the Hemenway Collection had acquired several hundred more volumes of early American history books, while donations and purchases furnished the library with 18th and early 19th century books by Caroline Fry, Sarah Trimmer, Hannah More, and Daniel Ramsay, among others [16].

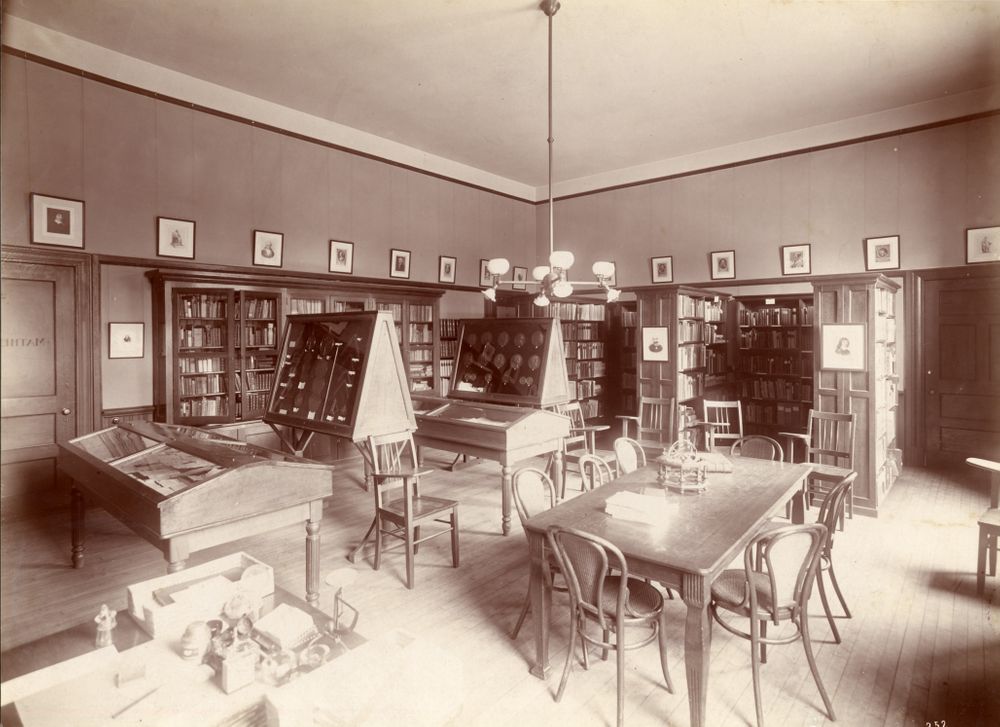

Mathematics Department. Library (Seminar Room). Teachers College. (Ca. 1910)

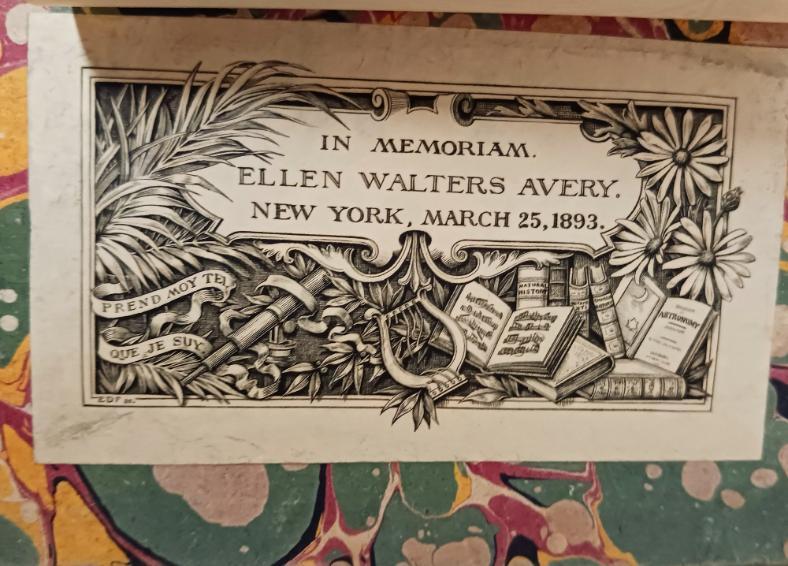

When Lilian Denio retired from Teachers College at the end of 1896, Elizabeth G. Baldwin took on the role of librarian. Baldwin, like Denio, had a background in cataloging, and sensing great opportunities at Teachers College, she left her position as head of Columbia University Library’s cataloging department to oversee the Bryson Library [17]. Baldwin’s early reports highlight her interest in making the catalog more accessible and usable for students and faculty while also underscoring her strong desire to increase the library’s humanities holdings [18]. In a June 1897 report, she recorded a donation of nearly 800 volumes of English and American poetry gifted to the library by Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Putnam Avery in memory of their daughter, Ellen Walters Avery, which established the Avery Collection of Art and Literature (the catalog of which can be found on HathiTrust) [19]. The donation to the Avery Collection included 108 volumes of Bell's Edition: The Poets of Great Britain Complete from Chaucer to Churchill. In that same year, the Hemenway Collection of American History, Archaeology and Art grew to 520 volumes [20].

Bookplate in Memoriam: Ellen Walters Avery

By the next year, the Hemenway Collection expanded through the purchase of the Works of Daniel Webster and The Works of the Late Dr. Benjamin Franklin, alongside other titles related to American history [21]. Monetary donations contributed to funds for the purchase of city, state, and national school reports, while donations of books, pamphlets, and manuscripts added to the Bryson Library’s rare books and manuscripts collection. In 1898, Mrs. H. O. Mayo (Mary Nevins Townsend Mayo) enriched the library’s collections with her gift of Robert Burns’s manuscript of “The Banks of Doon” [22]. Thanks to continued donations and purchases, the library reached 10,000 volumes of circulating material by March of 1898 [23].

Elizabeth Baldwin’s 1899, 1900, and 1901 reports indicate a busy and productive time for the library and its ever-growing collections. The Avery Collection increased by 1,200 volumes in 1899 – both through donations made by the Averys as well as through the establishment of a fund for the collection [24]. The Library Committee of the Union League Club donated 49 volumes of Dr. Henry Barnard’s work to the library, which were incorporated into the special collection of the Educational Department while students of the late Professor Dinwiddie donated approximately 30 books by or about the poet Robert Browning in the professor’s memory [25]. By 1900, the library held some 14,240 books, pamphlets and periodicals, thanks in part to Columbia University’s Libraries supplying educational periodicals from the United States, Britain, Germany, and France [26] . In addition to this agreement, Elizabeth Baldwin entered into an arrangement with textbook publishers in New York and Chicago to start a textbook collection at the library [27]. This collection expanded with the help of Mr. A.P. Marble, who “gave about seven hundred” books, as well as Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler and the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, who donated further samples of American curricula and pedagogical texts [28].

Throughout the early 1900s, the special collections established under Lilian Denio and Elizabeth Baldwin increased their holdings and became more defined in their aims. In 1902, Baldwin purchased several hundred 19th century French textbooks in the fields of mathematics, music, anatomy, and physical education while also using funds from donors to secure books in natural sciences and biology [29]. To meet the demands of students and faculty, Baldwin and the library staff focused their purchasing efforts on collecting educational literature, procuring early American school books, contemporary British textbooks in mathematics and classical studies, as well as Swiss, French, and Italian school books on hygiene and physical education [30]. Anticipating further developments in the field of physical education, Baldwin sought out rare and antiquarian German periodicals and books dealing with gymnastics, fencing, and children’s play [31]. During this period, the Avery Collection also gained several hundred more volumes through continued donations of both books and funds by the Averys. Other important additions to the library’s special collections and rare books included a donation from Samuel P. Avery of Sherman F. Denton’s As Nature Shows Them: Moths and Butterflies of the United States, East of the Rocky Mountains [32].

Baldwin’s purchasing efforts focused largely on the fields of educational history and educational research. Throughout 1905, she continued collecting pamphlets and textbooks from England, Germany, and France, and purchased a unique and rare collection of books on dance, which included Feuillet’s Choregraphie, ou l’art d'écrire la danse, Blasis’ Code of Terpsichore, and Noverre’s Lettres sur la danse, et sur les ballets [33]. In 1906, Baldwin and her staff purchased 125 out-of-print English and German educational books dating from the early 19th century. Among these purchases were Horne’s The Philosophy of Education and O’Shea’s Education as Adjustment [34]. Baldwin was determined to compile “complete collections of material on Education in all important countries of the world for the use of students in comparative education investigation” [35]. In her view, the library needed both historical and current materials from Holland, Belgium, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy and she hoped to acquire educational administration documents, treatises on elementary schools, documents on special and technical schools, sample textbooks, and lesson plans [36].

Further purchases in 1907 included books such as Guex’s Histoire de l'instruction et de l'éducation, Hunziker’s Geschichte der schweizerischen volksschule in gedrängter darstellung mit lebensabrissen der bedeutenderen schulmänner und um das schweizerische schulwesen besonders verdeinter personen bis zur gegenwart, and work by Ludvig Schrøder, as well as German and Austrian monographs on school reform and official reports from educational institutions [37]. Baldwin also concentrated efforts on purchasing rare educational treatises and manuscripts, including works by Petrus Ramus, Johannes Sturm, Wolfgang Ratichus, Jakob Wimpheling, Ulrich Zwingli, Johann Bernhard Basedow, Joachim Heinrich Campe, Juan Luis Vives, and Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi [38]. Such purchases altered the international rare book market, and in her 1908 report, Baldwin discusses such effects:

…according to statements made by foreign dealers, prices of educational books have increased as a direct result of numerous purchases made by Teachers College during the past three years. Because of our demands for this kind of literature in the past, we must pay higher prices in the future.[39]

Rising prices did not deter Baldwin in her quest to procure rare books and manuscripts for Bryson Library’s Special Collections. She branched out from traditional educational materials on language, mathematics, and philosophy and began seeking books and manuscripts related to the School of Household arts, particularly the subdivisions of Food and Cookery as well as Nutrition and Economics. By June of 1908, the Bryson Library had the beginnings of a special cookbook collection, consisting of “twenty-five old and valuable cook books and treatises on domestic economy” which were purchased “from second-hand book dealers and at auction” [40]. The new collection included Lydia Maria Child’s The Frugal Housewife and works by Harriet Beecher Stowe [41].

Elizabeth G. Baldwin, Librarian, 1862-1927. Teachers College. (Date Not Known)

While Elizabeth Baldwin sought to grow the collection in subjects outside education and the history of education, she did not neglect these areas of collection development. Alongside other Teachers College Faculty and staff, Baldwin served on a committee to collect materials on education from Australia, Canada, Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, as well as Latin American countries [42]. She also liaised with students to acquire important works for departmental libraries and their special collections. With the assistance of James D. Phelan, a graduate student at Teachers College, 485 volumes and pamphlets consisting of official reports, treatises and textbooks on French education were acquired in 1906 [43]. Several students from China also participated in collection development, helping Baldwin and library staff acquire and catalog over 500 Chinese books and pamphlets [44].

Additionally, Baldwin worked with Faculty members to determine gaps in the collection. In 1908, Dr. A. A. Snowden, procured several hundred books and pamphlets for the Bryson Library on French Education, including several “theoretical treatises written in the 18th. century” [45]. Dr. Snowden’s contribution included works by Rousseau such as Discours qui a remporté le prix à l'Académie de Dijon en l'année 1750: Sur cette question proposée par la même académie : si le rétablissement des sciences & des arts a contribué à épurer les mœurs [46]. Other important additions to the library’s antiquarian and rare manuscripts collections included German books on physical education authored by such thinkers as J.C. Lion, Johann Christoph Friedrich Guts Muths, Hugo Rothstein, Karl Euler, and Lorenz Grasberger [47].

In addition to increasing the library’s acquisitions, Baldwin and her staff worked to preserve the rare and older works held in the library. In her 1900 report, Baldwin notes that apart from acquiring books, the library staff also focused on “preserving the annual reports, catalogues, circulars, and other publications of certain schools and academies in this country” [48]. Through this work, Baldwin and the Bryson Library staff began serious efforts to maintain vital documents for prolonged use and access. Baldwin’s report suggests that many of these reports would have been discarded without the Bryson Library’s concentrated effort to curate as comprehensive a collection of educational materials as possible [49]. Many of the rare and antiquarian books acquired from European sources also required special treatment for their preservation and several books were rebound or placed in locked cases, only accessible with the permission and assistance of library staff [50].

Alongside preservation work, the Bryson Library exhibited its special collections. In 1899, Teachers College established the Educational Museum and by 1903, the library began coordinating with the museum to collect exhibition items as well as curate exhibits from its own holdings [51]. Elizabeth Baldwin liaised with various publishers to procure 150 mathematics textbooks for an exhibit in the Educational Museum in November 1903 [52]. In 1904, she received over 390 books on pedagogy in French and German, which were then displayed in the Educational Museum [53]. Further library-related exhibits in the Educational Museum included an exhibit of 100 donated books on religion, bible study, religious history, exegesis, and biographies in 1905 [54]; an exhibit depicting industrial drawings and other school work from Dutch and German schools in 1907 [55]; an exhibition of children’s literature in 1906 and again in 1913 which included works from Peter Parley (Samuel G. Goodrich), Maria Edgeworth, John Aiken, Isaac Watts, Anna Letitia Barbauld, Mary Martha Sherwood, and Mary Russell Mitford [56]; and a display of educational manuscripts and books from Germany, England, and New England town records, including the theologian Melanchthon's Sentenciae Veterum [57]. However, 1913 was the last year in which Baldwin worked with the Educational Museum, as its funds were withdrawn by 1914.

Educatonal Museum. Mathematical Exhbit. Teachers College. (Ca. 1903)

The 1910s and early 1920s saw continued growth of the library’s collections as a whole, but the special collections particularly flourished during this time. From 1910-1922, the Avery Collection, the textbook collection, and the educational resource collection expanded by thousands of volumes [58]. In 1920, the Bryson Library gained another important collection in the Adelaide Nutting Historical Nursing Collection. Students, colleagues, and friends of faculty member Adelaide Nutting donated over 200 published works, manuscripts, and historical reports to the library in honor of Professor Nutting and her founding of the Department of Nursing Education [59]. In addition to the Adelaide Nutting Historical Nursing Collection, the library worked with the school of Practical Arts to acquire over 500 cookbooks, nutritional treatises, textile and clothing manuscripts, works on town planning, and home economy texts for the Practical Arts special library by the summer of 1922 [60].

Teachers College Library Adelaide Nutting Bookplate

Baldwin continued to enrich the collection through purchases and requests. She placed emphasis on growing the Adelaide Nutting Historical Nursing Collection, working with donors to acquire materials related to the life and work of Florence Nightingale, including letters, biographies, and articles [61]. Not satisfied with focusing on just one collection, Baldwin also purchased early juvenile literature, Greek and Latin textbooks from the 1550s through the 1780s, and early 19th century works on music instruction [62]. While Baldwin noticed a decline in scholarly interest in the history of education, she was determined to continue collecting historical texts [63]. In 1923, she purchased Matthew Poole’s Model for the Maintaining of Students at Choice Abilities at the University and Anna Maria Schurman’s The Learned Maid; or, Whether a Maid May Be a Scholar, in the hopes that such works would enrich not only the library’s reputation but also enrich the study of education [64]. At the same time, Baldwin contacted antiquarian booksellers to acquire 18th and 19th century French and English texts on cooking and household management to meet the demands of the School of Practical Arts [65].

Teachers College Library

By the 1920s, the Bryson Library was running out of space. Collections’ growth and the need for more student study spaces demanded that the library transform once again. While Elizabeth Baldwin’s reports mention plans for a new building in 1917, it wasn’t until 1924 that Russell Hall was built, allowing for the library to occupy the top four floors of the new building [66]. The library at Russell Hall, known as Teachers College Library, allowed for the creation of dedicated exhibition space for special collections items, as well as closed stacks specifically for the storage of rare books and manuscripts [67]. Until her death in 1927, Elizabeth Baldwin continued to oversee the development of distinct and special collections, such as the Avery Collection, the Adelaide Nutting Historical Nursing Collection, the textbook collection, and the cookbook collection [68]. For 30 years, she worked to meet the needs of students, faculty, and outside researchers, developing the Teachers College Library into a unique research library, which contained one of the largest collections of educational materials and manuscripts. In her honor, the trustees established the Baldwin Collection, a library collection commemorating her service to the college [69].

Russell Hall. Library. Curriculum Reading Room (Floor 5). Teachers College. (Ca. 1920)

Succeeding the formidable Elizabeth Baldwin was Charles E. Rush, another librarian from Columbia University [70]. Rush only served as Librarian from 1928 to 1931, but under his administration, the Teachers College Library saw several new acquisitions and projects related to the special collections. Rush established policies for the exhibition of rare and historical items, working with library staff to make contacts with important booksellers and utilize resources already held by the library [71]. Rush procured cabinets and display cases for this purpose, which allowed students and faculty to view “rare books, prints, records, and other items” [72]. Rush’s projects also included the creation of policies for the purchasing of special collections items, although his reports do not specify the terms of such policies [73]. Rush purchased a large collection of 19th century materials on American education from Harvard’s library in the effort to fill gaps in the collection, while also working with donors and friends of the college to secure books, pamphlets, and other materials [74]. Donations of rare and historical items flourished during Rush’s short tenure, with notable contributions from Mrs. Talcott Williams, Mary G. Potter, Dr. David Eugene Smith, and Paul Monroe [75]. Rush also oversaw an influx of gifts to the Adelaide Nutting Historical Nursing Collection, as 1930 commemorated the thirtieth anniversary of the Department of Nursing Education [76].

When Rush stepped down from the role of librarian, Eleanor M. Witmer was chosen to succeed him. Witmer had an extensive background in librarianship and education: she had attended the Library School of the New York Public Library, held a Master of Arts in English, and had worked as a cataloger and assistant teaching librarian before coming to Teachers College in 1931 [77]. Over the next 30 years at Teachers College, Witmer introduced library instruction, published guides and handbooks for students and faculty, and embraced new media, focusing on building up the library’s audiovisual resources [78]. She also worked to bolster the library’s special collections. In Witmer’s first year at the library, she established a special collection of literature relating to women with the help of a donation from the late Dr. Anna Garlin Spenser [79]. Dr. David Eugene Smith also donated close to “one thousand books, rare manuscripts and documents pertaining to education and the history of nursing,” bolstering the resources available to scholars [80]. Moreover, Witmer endorsed the creation of bookplates by staff, adding to the already rich bookplate collection held by the college, which was further expanded in 1935 by the addition of Adelaide Nutting’s bookplate collection [81].

Portrait of Eleanor Montgomery Witmer, 1899-Unknow. Teachers College (Ca. 1933).

In addition to collection development, Eleanor Witmer devoted her time to hosting exhibitions at the Teachers College Library. In 1935, she set up exhibits showcasing the prints of the late Arthur Wesley Dow and his students, curated exhibits utilizing the works and manuscripts of David Eugene Smith, and coordinated with other museums and libraries across New York City to show rotating exhibitions of important works [82]. Witmer saw such exhibits as “displays of educational value” which linked “the greater resources of New York City with student needs and interests” [83]. In 1936, the library held 25 exhibitions, which included an exhibit of Anatolian rugs collected by Professor Paul Monroe [84]. Witmer’s last exhibition, as per a 1962 report from the acquisitions department, consisted of a collaboration with the Nursing Education Department to display items related to Florence Nightingale, including nursing cuffs and a veil [85].

Throughout the 1930s, gifts and purchases continued to enrich the special collections. Witmer’s 1932 report records a donation of manuscript notebooks from the Kitchen Garden Association, one of Teachers College’s forerunner institutions [86]. Professor George S. Counts also donated several important Russian books dealing with sociology and education [87]. In 1934, Mrs. Mary H. McKesson gifted the library with 200 historical textbooks from the library of Reverend Samuel Jones [88]. That same year, Witmer and her staff acquired the personal library of Patty Smith Hill, which largely contained materials related to the kindergarten movement [89]. Enriching the collections with further historical educational texts, Professor Eugene David Smith donated First Principles of Arithmetic for the Use of Very Young Children to the curriculum collection in 1936, while Professor Paul Monroe also presented the college with early educational books and manuscripts [90].

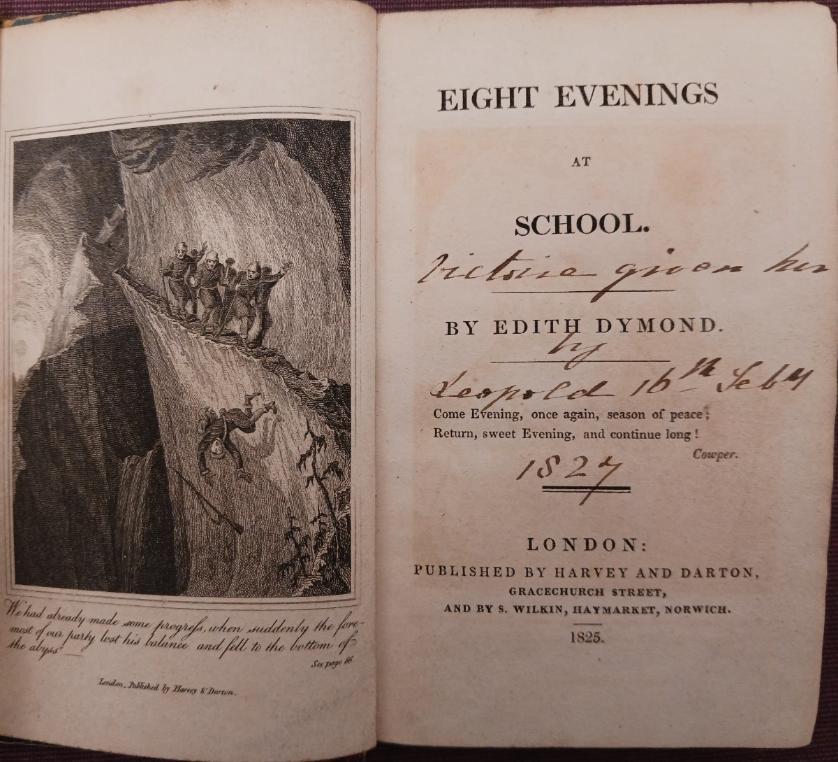

Among the most important and unique collections acquired during this period was the Harvey Darton Collection. In 1939, American book collector Carl Pforzheimer gifted the Harvey Darton Collection of early English Children’s literature to the Teachers College Library [91]. The collection, replete with an annotated bibliography, contains approximately 900 titles of seventeenth and eighteenth children’s literature collected by Frederick Joseph Harvey Darton, an English book collector and historian of children’s literature [92]. Included in the collection are a first edition of Francis Osborn’s Advice to a Son and Edith Dymond’s Eight Evenings at School (1825), which was given to Queen Victoria by her Uncle King Leopold, I. The book contains the Queen’s autograph inscription on the title page. Witmer observed that the Darton collection “greatly strengthens the resources for studying educational and social thought in seventeenth and eighteenth century England. It places within the reach of scholars some materials not hitherto available in England and America” [93]. Housing such a collection, cataloging it, and preserving it allowed previously inaccessible materials to be made available to the larger research community.

Edith Dymond’s Eight Evenings at School with Queen Victoria’s autograph

Apart from preparing resources for research use, Witmer and her staff took on projects to develop the Teachers College Historical Collections as well as establish an archive. In 1931, Witmer set her sights on surveying, organizing, and cataloging what she called “the mess of historical material relating to Teachers College and its predecessors” [94]. The upcoming fiftieth anniversary of Teachers College highlighted the importance of the institution’s historical records and called for the creation of Teachers Collegiana (TCana) Collection, or manuscripts, books, pamphlets, bulletins, reports, catalogs, photographs, and ephemera produced by those connected with the College and its history [95]. Witmer’s reports underscore the breadth and depth of the collection, and the difficulty of assembling it. She wrote of the need to “assemble much of [TCana] from scattered files in Teachers College and to obtain more from living alumni” [96]. She sent letters requesting such materials to various College offices, retired faculty, alumni, and Kitchen Garden Association members such as Kate L. Olcott. Particular emphasis was placed on collecting Kitchen Garden Association records, student publications, and catalogs from the Horace Mann School [97].

In her 1938 report, Witmer noted the need for professional staff to take on the challenge of assembling TCana and other Teachers College historical records. She wrote, “the services of a curator would be necessary to bring [the historical records] and existing records into shape” [98]. Such a curator, or archivist, would be responsible for organizing, arranging, and preserving the records. But with their small budget and limited resources, Witmer and her reference staff had to make do themselves. Witmer created a tentative list of TCana collections and their classifications, allowing staff to begin organizing and cataloging efforts [99]. By 1939, she declared, that the collection of Teachers Collegiana had been “brought into a semblance of order and is now being analyzed and cataloged” in the hopes of making such items accessible to researchers [100].

By the 1940s, Witmer was deep in the throes of expanding the archival collections at Teachers College, despite the demands of the war. In a document titled “Tentative Draft of Procedures for Enlarging the Archival Collections at Teachers College,” Eleanor Witmer worked to define an archive in the context of the College. In her conceptualization, the Teachers College Archive would be comprised of “the whole of the written documents, drawings and printed matter officially received or produced by Teachers College (or its predecessors) or any of its officials, in so far as these documents were intended to remain in the custody of the college or the official” [101]. For the library to steward these archives, Witmer suggested that there needed to be a “detailed statement on the structure of teachers college and its predecessors”[102]. She furnishes the following statement as an example:

The archives come into being as the result of the activities of an administrative body or official and are the reflection of the function of that body or official. A careful listing of all the administrative bodies which have existed or do exist in Teachers College (or its predecessors) will enable the archivist to systematically search for the documents they produced. Records of the operations and activities of each administrative unit should be traced. [103]

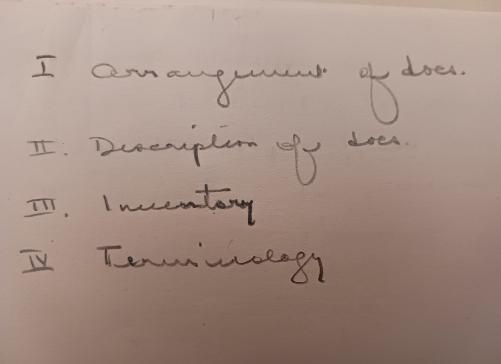

Witmer proposed the following activities as essential for the institution’s archival work: inventorying the known archival collections; proposing unknown or potential collections; establishing procedures for accessioning and processing collections; and creating policies which would dictate the “arranging, describing and recording documents in the collection” [104].Witmer emphasized the need to contextualize and document Teachers College’s history and offices before establishing an archive.

The final step of the process of expanding and evolving the archives should include researching, indexing, and analyzing whole collections to furnish researchers with “chronological guides” [105]. This work, she stressed, should be ongoing. To prepare for the eventual expansion of the archives, Witmer wrote copious notes on the subject. On several note cards, she worked through her conception of an archive, citing definitions and suggestions from the Bulletin of the National Archives as well as the Manual for the Arrangement and Description of Archives by Muller, Feith, and Fruin (1940). She conceptualized the kinds of materials an archive should contain; detailed the necessary equipment; and plotted out the beginnings of different collections: administrative collections; educational departments’ files; and historical documents on the founding of Teachers College [106].

In a January 11, 1945 letter attached to the draft procedures, Witmer informed Dean William Russell that the college had some five hundred items in the historical and archival collections [107]. Correspondence between Witmer and the Dean indicate that there was keen interest in the historical records of Teachers College, but uncertainty regarding the labor needed to process the archives left the collections inaccessible to researchers [108]. The daunting nature of the impending archival work perhaps led Eleanor Witmer to suggest the librarians catalog important collections but allow for departments to retain custody of their own materials [109]. Through catalog cards and record abstracts collections could become accessible to students and faculty if departments gave permission for research use. In frustration over the lack of resources, Witmer wrote, “I see no one on the Library Staff who is well equipped to do the studying, searching, describing, etc. which will be a necessary part of this work” [110]. She stressed the need to find a trained archivist, and in the margins of a December 4, 1944 letter from Dean Russell supporting the library’s archival efforts, Witmer wonders, “Can an archivist be found?” [111].

One of Eleanor Witmer’s notecards sketching out Teachers College Archives

In the spring of 1945, Eleanor Witmer attempted to find an archivist for the library. She reached out to R.G. Vail, director of the New York Historical Society, to inquire about hiring an archivist for Teachers College. Vail responded on April 24, 1945, regretfully noting, “I am very much afraid that you will have a great deal of difficulty in finding [an archivist]. Most of the available people were long since snapped up by the National Archives at Washington” [112]. He then goes on to suggest that Witmer “pick a recent graduate of the Library School at Columbia and train her for the job, for I very much doubt you will find an experienced person available” [113]. From the available records, it seems that Witmer and her staff took on the responsibility of the college’s archives themselves.

Without an archivist, Witmer focused her efforts on other areas of the library. Post-war activities saw library staff corresponding with government officials around the globe, hoping to acquire texts on education from countries like Japan, New Zealand, and Russia [114].However, after 1945, Witmer’s library reports and other library related records contain gaps or silences when it comes to the special collections and archives. The library records and reports do not mention the special collections again until Witmer’s 1959/1960 report – her penultimate one. In the report, she mentions that the cataloging department was able to process and catalog the Darton Collection as well as “thousands of private school catalogs of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries” [115]. This work, she hoped, would make research collections more accessible.

1960 also saw Witmer and her staff acquire Katherine Camp Mayhew’s papers, which contained materials produced and gathered during Mayhew’s time at John Dewey’s Laboratory School at the University of Chicago [116]. Strangely, Witmer’s 1960/61 report omits this acquisition. The papers have since been transferred to Cornell University’s archives. Up until her retirement in 1961 Witmer’s reports were focused more on reference and instruction work, circulation statistics and weeding, and library publications. By the time she retired in 1961, she left the library with a large audiovisual collection and had initiated a large-scale microfiche project to preserve older and more fragile materials [117]. She laid the groundwork for the next librarian, Sidney Forman, to mold the library into a world-reknowned research library.

Notes:

[1] Typed Manuscript “A History of the Library of Teachers College,” by Brian Aveney January 1966. RG 10: Library Records: Unprocessed Library?, box 1 of 2. Library Records (hereafter cited as Typed Manuscript, Brian Aveny, Library Records).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Witmer, Eleanor M., and May B. Van Arsdale. Introducing Teachers College: Some Notes and Recollections. New York: Bureau of Publications, Teachers College, 1948, 9.

[4] Typed Manuscript, Brian Aveny, Library Records, 12.

[5] Lilian Denio, “Report of the Librarian, 1890-1895” (unpublished manuscript) typescript and handwritten manuscript.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Denio, “Report of the Librarian” (unpublished manuscript, December 1, 1892) typescript.

[9] Ibid, 2.

[10] Ibid., 2.

[11] Denio, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, February 16, 1893), typescript, 2.

[12] Denio, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, October 15, 1894), typescript, 3.

[13] Denio, “ Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, February 1895), typescript, 2.

[14] Ibid., 2.

[15] Denio, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, June 15, 1895), typescript 2-5.

[16] Denio, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, March 15, 1897),typescript, 2.

[17] Typed Manuscript, Brian Aveny, Library Records, 13.

[18]. Elizabeth G. Baldwin, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1897), typescript, 1.

[19] Ibid., 1.

[20] Ibid., 4

[21] Baldwin, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, March 15, 1898) typescript and handwritten, 1.

[22] Ibid., 1

[23] Ibid., 1

[24] Baldwin, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, November 15, 1899) typescript.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Baldwin, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, September 11, 1900) typescript, 1.

[27] Baldwin, “Report of the Library,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1901) typescript, 1.

[28] Ibid., 2-3.

[29] Baldwin, “Report: Bryson Library,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1902) typescript, 3-4.

[30] Baldwin, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1903) typescript, 3.

[31] Ibid., 3.

[32] Baldwin, “Report: Bryson Library,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1901), typescript, 2-3.

[33] Baldwin, “Annual Report: Bryson Library,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1905) typescript, 4.

[34] Baldwin, “Annual Report: Bryson Library,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1906) typescript, 2.

[35] Baldwin, “Annual Report: Bryson Library,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1907) typescript, 1.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid., 7

[38] Ibid., 8.

[39] Baldwin, “Annual Report: Bryson Library,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1908) typescript, 1.

[40] Ibid., 2.

[41] Ibid., 2.

[42] Baldwin, “Report of the Librarian, Annual Report: Bryson Library,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1908) typescript, 9-10.

[43] Baldwin, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, 1906) typescript, 1-2.

[44] Baldwin, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, 1920) typescript, 5.

[45] Baldwin, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, 1908) typescript, 2.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Untitled Sketch on Bryson Library by Elizabeth Baldwin, 1908, RG 10: Library Records - TCANA Vertical Files, Announcements (20 – Cafeteria, Folder 13: Archives. (Hereafter cited as TCANA Vertical Files, Folder 13: Archives).

[48] Baldwin, “Report of the Librarian,” (untitled manuscript, September 11, 1900) typescript, 5.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Baldwin, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30th, 1903) typescript, 3.

[51] Baldwin, “Report of the Bryson Library,” (unpublished manuscript, 1904) typescript, 1.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Baldwin, “Annual Report: Bryson Library,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1905) typescript, 3.

[54] Ibid, 4-5.

[55] Baldwin, “Annual Report: Bryson Library,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1907) typescript, 1.

[56] Baldwin, “Annual Report: Bryson Library,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1911) typescript, 2.

[57] Untitled report by Elizabeth Baldwin, n.d., TCANA Vertical Files, Folder 13: Archive.

[58] Baldwin, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, 1910) typescript, 2; “Report of the Librarian” (unpublished manuscript, 1911) typescript, 2; “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, 1912) typescript, 2.

[59] Baldwin, “Annual Report: Bryson Library,” (unpublished manuscript, 1922), typescript, 2; Baldwin, Elizabeth G. “The Teachers College Library.” Teachers College record (1970) 26, no. 6 (1925): 498–510.

[60] Baldwin, “Annual Report: Bryson Library,” (unpublished manuscripts, 1917-1920) typescript.

[61] Baldwin, “Annual Report: Teachers College Library,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1923), typescript, 3.

[62] Ibid., 2.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid., 3.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Baldwin, “Annual Report: Teachers College,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1924) typescript; Typed Manuscript, Brian Aveny, Library Records, 20-21.

[67] Baldwin, “Annual Report: Teachers College,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1925) typescript, 4-5.

[68] Baldwin, “Annual Report: Teachers College,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1927) typescript.

[69] Baldwin, Elizabeth G. “The Teachers College Library,” 1925, 504.

[70] Rush, Charles E. “Annual Report: Teachers College,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1927) typescript.

[71] Report, “Report of the Librarian,” by Charles E. Rush, 1928, RG 10: Library Records, Unprocessed Library Records, Box 1 of 2, Folder: “Librarians’ Annual Reports thru 1961/1962,” 4. (Hereafter cited as Rush, “Report of the Librarian” or Rush, “Annual Report”.)

[72] Rush, “Annual Report,” (unpublished manuscript, 1930) typescript.

[73] Ibid., 3.

[74] Rush, “Annual Report,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1928) typescript, 1.

[75] Rush, Annual Reports, 1929-1930.

[76] Rush, “Annual Report,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1930) typescript, 7-8.

[77] Typed Manuscript, Brian Aveny, Library Records, 29.

[78] Ibid.

[79] Report, “Report of the Librarian,” by Eleanor M. Witmer, 1931 RG 10: Library Records, Unprocessed Library Records, Box 1 of 2, Folder: “Librarians’ Annual Reports thru 1961/1962,” 6. (Hereafter cited as Witmer, “Report of the Librarian” or Rush, “Annual Report”.)

[80] Ibid.

[81] Witmer, “Annual Report,” (unpublished manuscript, 1935) typescript, 6.

[82] Ibid., 3.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Witmer, “Annual Report,” (unpublished manuscript, 1936) typescript, 6.

[85] Report, “Acquisitions Department Annual Report: July 1961 - June 1962,” by Elizabeth Herrick, July 2, 1962, RG 10: Library Records, Unprocessed Library Records, Box 1 of 2, Folder “Librarians’ Annual Reports thru 1961/1962.”

[86] Witmer, “ Report of the Librarian for the Academic Year Ending June 30, 1930,” (unpublished manuscript, June 30, 1930) typescript, 6.

[87] Ibid.

[88] Witmer, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, 1934) typescript, 4.

[89] Ibid.

[90] Witmer, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, 1936) typescript, 7.

[91] Witmer, “Annual Report,” (unpublished manuscript, 1939) typescript, 6.

[92] Provenzo, Eugene F. “A Note on the Darton Collection, Special Collections, Teachers College, Columbia University.” Teachers College record (1970) 84, no. 4 (1983): 929–934.

[93] Witmer, “Annual Report,” (unpublished manuscript, 1939) typescript, 6-7.

[94] Ibid., 4.

[95] Witmer, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, 1938) typescript, 1.

[96] Ibid., 1.

[97] Eleanor Witmer to Miss Feagley, Miss Beers, and Miss Derring, 28 April 1939. RG 10: Library Records, TCANA Vertical Files, Box 2: Announcements (2) -- Cafeteria, folder 13: Archives; Eleanor Witmer to Grace L. Aldrich, 19 January 1939, RG 10: Library Records, TCANA Vertical Files.

[98] Witmer, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, 1938) typescript, 2.

[99] Typescript of “TCana Classifications” by Eleanor M. Witmer, n.d., RG 10: Library Records, TCANA Vertical Files, Box 2: Announcements (2) -- Cafeteria, folder 13: Archives.

[100] Witmer, “Annual Report,” (unpublished manuscript, 1939) typescript, 4.

[101] Typescript, “Tentative Draft of Procedure for Enlarging the Archival Collections at Teachers College” by Eleanor M. Witmer, 11 January 1945, RG 10: Library Records, TCANA Vertical Files, Box 2: Announcements (2) -- Cafeteria, folder 13: Archives, 1.

[102] Ibid.

[103] Ibid.

[104] Ibid.

[105] Ibid., 2.

[106] Handwritten notes on archives by Eleanor M. Witmer, n.d., RG 10: Library Records, TCANA Vertical Files, Box 2: Announcements (2) -- Cafeteria, folder 13: Archives.

[107] Eleanor M. Witmer to William F. Russell, 11 January 1945, RG 10: Library Records, TCANA Vertical Files, Box 2: Announcements (2) -- Cafeteria, folder 13: Archives.

[108] Eleanor M. Witmer to William F. Russell, 30 November 1944, RG 10: Library Records, TCANA Vertical Files, Box 2: Announcements (2) -- Cafeteria, folder 13: Archives.

[109] Ibid.

[110] Eleanor M. Witmer to William F. Russell, 11 January 1945, RG 10: Library Records, TCANA Vertical Files, Box 2: Announcements (2) -- Cafeteria, folder 13: Archives.

[111] William F. Russell to Eleanor M. Witmer, 07 December 1944, RG 10: Library Records, TCANA Vertical Files, Box 2: Announcements (2) -- Cafeteria, folder 13: Archives.

[112] R.G. Vail to Eleanor M. Witmer, 24 April 1945, RG 10: Library Records, TCANA Vertical Files, Box 2: Announcements (2) -- Cafeteria, folder 13: Archives.

[113] Ibid.

[114] Witmer, “Report of the Librarian,” (unpublished manuscript, 1946) typescript, 3.

[115] Witmer, “Annual Report 1959/60,” (unpublished manuscript July 5, 1960) typescript, 2.

[116] Franck, Jane P. “An Almanac for the First Century,” Milbank Memorial Library 1988. Library Records, Ephemera, RG 1 -RG 10: Folder: Library Publications. (Hereafter cited as “An Almanac for the First Century,” 1988).

[117] Witmer, “Report of the Librarian 1961/1962,” (unpublished manuscript, 1962) typescript.

Read more. Part II: 1962-2024