My Dear Miss Nutting, Personal Experiences of Nurses in France During World War I

Oh, The Things You Can Find

In box nine of Record Group 20: Department of Nursing Education Archive, folder 536 sits slim and unassuming behind a piece of archival cardboard with the abbreviation “MISC”. The folder, labeled “World War I—Miscellaneous. Personal Experiences of Nurses Nursing in France—Correspondence”, is arranged both physically and intellectually, at the end of material largely related to a crisis in nursing. The crisis resulted as graduate schools experienced an exodus of graduate nurses from their domestic programs to join the Canadian Royal Army (prior to the United States involvement in the war) to assist the medical corps overseas in Belgium, France, The Netherlands, and England.

As nurses embarked on perilous journeys across the Atlantic to offer their services both at the front lines and in reserve hospitals, many other, primarily, young women, left the domesticity of the United States and headed overseas to join on as orderlies, or auxiliaries, to support the overwhelmed field hospitals. While the selfishness and bravery of these volunteers is lauded, it magnified the crisis as the anticipated trajectory of enrollment dwindled.

The Surgeon-General, as reported by Mary Adelaide Nutting, was recommending a push for graduate programs to fill 25,000 nursing vacancies to continue domestic support in healthcare. As such, Teachers College and the Department of Nursing proceeded to engage in a publicity campaign to drum up interest in not only its own program, but across the nation, while also advocating and ensuring that the programs met with a standard of education that would facilitate quality students and subsequent healthcare.

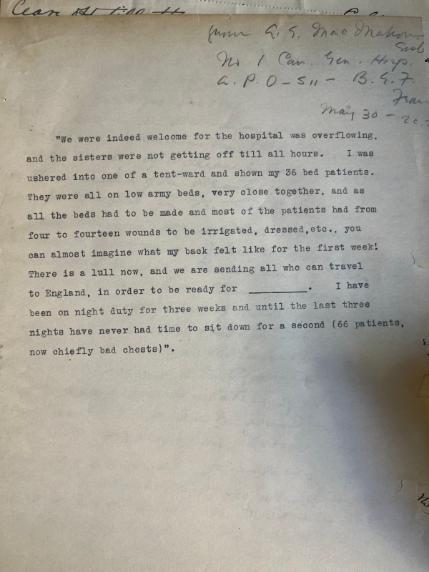

As part of an effort to ensure their continued training, many nurses continued their studies, first at military hospitals, and then functioned as training teachers for auxiliaries in field hospitals. Many of these nurses from Teachers College wrote letters back to Ms. Nutting and Goodrich about their experiences about the state of nursing. These individual testimonials piece together, individually, a unique personal and professional narrative on the nature of nursing during wartime.

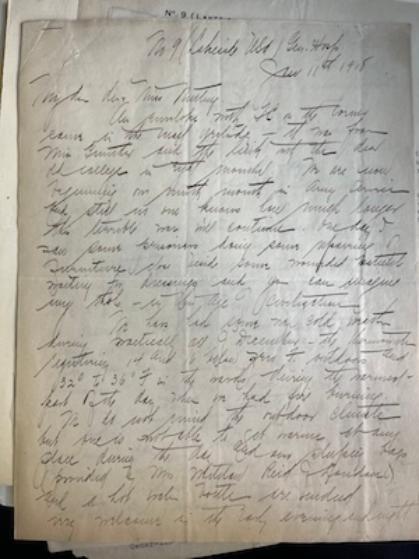

One letter from Maybelle B. Ross Thackery Hotel, written on may 11th, 1915, (Across from the British Museum) from a nurse on leave speaks about how her work in “Belgium was most interesting. Dr [ILLEGIBLE] ambulances was beautifully equipped and I should say well organized considering the variety of nationalities one has to handle” and that this has been the only place “where Drs. and nurses had the idea of war economy”, and that despite everything that they were facing “the spirit and discipline in the hospital was very good”.

The same letter details the frustrations of dealing with foreign government entities, especially the French army regulations—which were far from what the average, civilian nurses were accustomed to, especially since many nurses had to wait for their Canadian papers before being able to help, and it was found to be “deplorable to have French soldiers die from neglect and so many nurses doing nothing over here”.

Miss Thackery goes on to relay to Miss Nutting that the “nurses are very healthy, gowned in white, with close fitting caps” and “half has had previous war experience”. Thackery has been taking a much deserved “short holiday in Scotland”.

The tone takes a remarkable turn as she shares that she will be given an “elaborate Canadian military uniform”, which she deplores as a “mockery when one thinks of the awfulness of our work and what it really means” as she tries to “forget the face injuries of the 30th, September 1915 at the Battle of Champagne. The que of wounded waiting to be fed. Many times, it was hard to know where to begin. Some had been bombed on the 26th and had no dressings and very little food since then”

The shock of returning from the front is apparent as it is shocking as “Paris is quiet, many in mourning and any number of wounded are to be seen in the streets. Here, apart form darkness at night and soldiers, everyone appears too serene.”

Written from the American Ambulance Hospital in Paris, on July 14, 1916, Nurse Marth Last Name Illegible] speaks matter-of-factly about the state of the hospital in light of a major offensive that took place:

Since march we have had our hands full and of course this big offensive [Battle of Albert] is bringing more work. We expect a very hard summer before we are through. Only hope this will be the beginning of the end, but who can tell. Today is the French national holiday [Bastille Day]. Many of the doctors and nurses have gone to the parade but I stayed to be sure things were O.K. while so many were off, and am glad I did for we had two hemorrhages. This is certainly a place were good nursing counts. The complicated apparatus, preventing and care of pressure sores, catching of hemorrhages, etc. Many come from hospitals with dreadful sores. We treat them very successfully with exposure to electric light…All sorts of apparatuses for complicated fractures of arms and legs with …I wish you and Miss Goodrich [Anna Warburton Goodrich—teacher of hospital economics at TC starting in 1904] could see it all, you would be so interested. The combined work of dentists and surgeons on jaw cases have brought some wonderful results….

I certainly have my problems here. So many different interests and so many untrained people to handle. The untrained are however under the direction of the trained. There are many volunteers. This too gives to problems, but the spirit of the place is something I will always be glad to have known. We have everything in the way of orderlies, from a medical student…to a Russian Count. Sometimes my brain fairly whirls but is a splendid experience and am very glad I came.

Wish I could write more, there is so much of interest, but every minute is occupied. I will certainly have a few ideas on military hospitals when I am finished here.

Martha follows up in May of 1917 to Nutting, revealing the desperate need for nurses that are currently in graduate school, but also offers some insight into the teaching of non-professional auxiliaries in wartime, at the request of Miss Goodrich—the use of auxiliaries being used to fill the ranks due to the lack of professionally trained, graduate nurses:

All nurse aides or auxiliaries, as we call them here, taught first by a nurse in a teaching ward of which we have two, then have to work under direction of a nurse…the only way in which the non-professional can help on the ward is to have them work under direction of the nurses. The nurses are in charge of all the ward here now, the auxiliaries help very much as probationaries help at home. They make beds, dust, take temperatures, assist the nurses with dressings, application of apparatus etc.

They are not taught to give medicines, hypodermics or to be responsible for doing dressings, or application of apparatus etc. We teach them the simple nursing procedures and allow them to carry them out under the nurse’s direction otherwise we not hold their interest. Every auxiliary in the house is assisting some nurse, and that nurse is responsible for what her auxiliary does, so to speak. For example, on the large wards a nurse is given so many patients and an auxiliary to help her in the care of those patients. We have a great many ten bed wards. A nurse has two ten bed wards and an auxiliary in each of these wards to help her. In account of these ten bed wards, it would be almost impossible for us to nurse the number of wounded we do have without these auxiliaries. I hope in any hospital where they use auxiliaries, they will always place them directly under the direction of the Chief Nurse. Here they are practically so now, but it has been a long, hard pull…By degrees I have taken them from such work as operating room, dressing room, etc. till now there as only one place in the hospital where I still have an auxiliary, but feel that I should have a nurse, but must wait my opportunity.

Martha had recently come to oversee the “supervision of the surgical dressing room department”, where “here again auxiliaries do all the work. I was especially glad to have the direction of this department because I had wished to stop some of the auxiliaries, who smoked when the stopped to rest. I am glad to say we never see a cigarette in the department now. “

However, she goes on to state that there are so many problems and looks to Miss Nutting and Goodrich for advice, lamenting that only “some things can be improved, others can’t for lack of support. But we keep struggling on and hope for changes which will give us support”, though “there has been too much of the wrong kind of publicity about the place, newspaper pictures published, letters, etc., I am making every effort to control that as far as nurses are concerned, but unfortunately, I can’t control many that have gone. There is an element here that encourages that sort of thing, but I think it is gradually diminishing.”

Ultimately, she wonders if “our entry in the War will bring any change here. I can foresee that it might bring changes what would make the place go on or on the other hand improve very much. I do hope it will be the latter” and struggles with her specific role as “an American Red Cross Nurse and anxious to help, but felt it was easiest to stay here for the time at least” and how she ‘hate[s] to see our men come over, and yet want to be represented at the front.”

However, not every moment was spent fretting of war, supplies, and teaching. One Miss Baxter, stationed at Tenth Territorial Hospital in Florence, Italy was ”taking a rest on the sea shore” recovering from the strenuous summer months of 1916, which had witnessed the large scale offensive of the Battle of Somme, considered to be one of the bloodiest battles of the war.

Writing to Miss Nutting from Montrono, Toscana, Miss Baxter offers a description of the countryside worthy of comparison to Emerson or Thoreau:

[Y]ou never saw a more beautiful place then this. Imagine a perfect solitary, smooth sandy beach, stretching as far as eye can see, and a gloriously green sea with little white caps to the waves lapping the beach. Behind me is a wonderful fairy wood of stone pines with just enough brush wood and bramble to make it look quite wild, but no too much to interfere with our foraging sweet Williams and purple mint, or hunting innumerable mushroom for winter use. The light and shade in that wood are a matter for dreams. No painter ever painted its equal, and I cannot imagine am more ideal place for a nurse to rest in.

And rest she deserves as lately

[T]he work has been tremendous. Every time a batch of 20-25 wounded arrives, which is some time thrice a week we have to work night and day, I have done 30 hours on end. If it were always so, I could not of course stand it, but naturally after the poor creatures are settled down, the work gets systematized, and it is remarkable how quickly they get well, and make room for others. The hospital is on the Fiesole Hill [in Florence] and is open to all the seas and wind on that beautiful southern front.

Commenting further on the layout of the hospital,

[B]ehind the septic room where the greater part of our work is done, we have the aseptic room or regular operating room for clean operations, extraction of bullets, appendectomies, bone operations of all kinds…We have operations on fixed days…from three to ten a day. We have dear little isolation but out in the garden

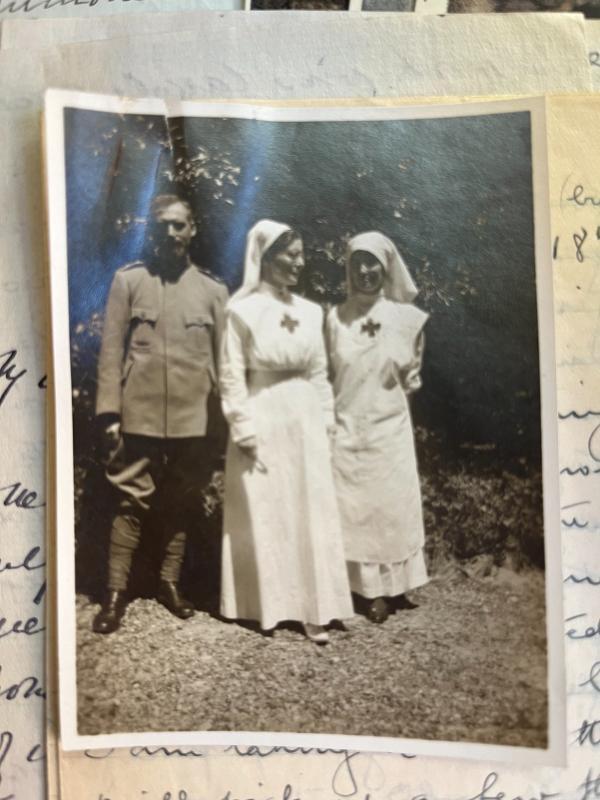

From Grace Baxter (middle): the male doctor is a “clever house surgeon” and the “girl” is presumably the nurse of the septic “medicheria” or surgical dressing room.

Many of the remaining letters vary in their descriptions of both hospitals, nursing, and life; the tone oscillating from optimistic to pessimism and everything in between.

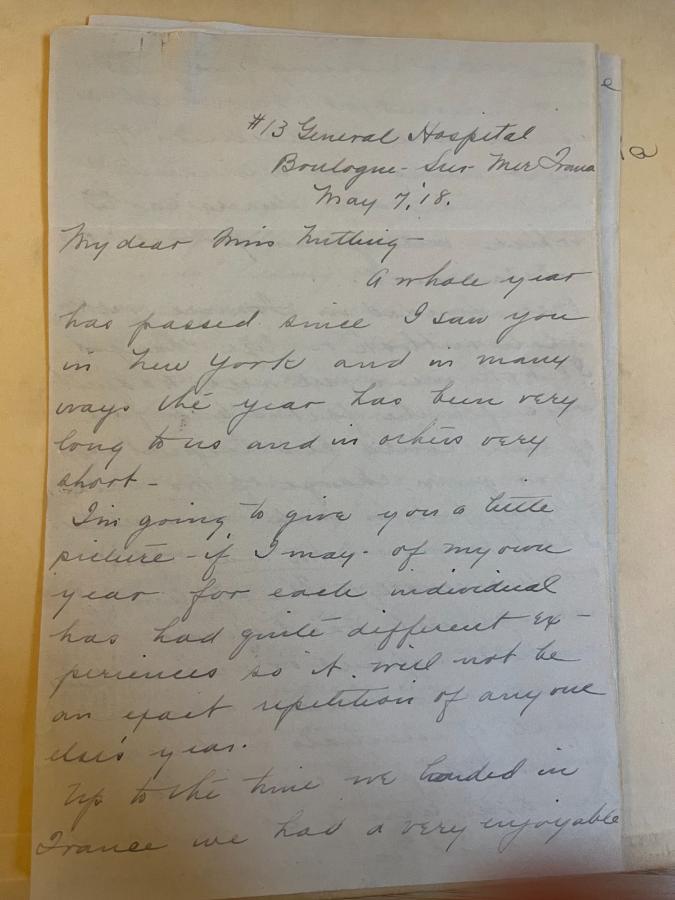

In reading through many of these letters, I found that Alice Lake provided a balanced reflection that captured the essence of the physical and emotional experience many of these nurses went through. Writing from #13 General Hospital, Boulogne-Sur-Mer, France. May 7, 1918:

A whole year has passed since I saw you in New York and in many ways the year has been very long to us and in others very short.

I’m going to give you a little picture—if I may of my own year for each individual has had quite different experiences so it will not be exact repetition of anyone else’s year.

Up to the time we landed in France, we had a very enjoyable time—our crossing was great and uneventful—but week in London was a succession of sight-seeing trips alternating with tea and theater parties which were given for our entertainment.

Once landed in France our whole outlook on life changed. It took me a full week to adjust myself to the fact a tent full of men could be a hospital ward. I was given charge of two wards of fifty-two beds in each—for assistants I had two nurses, two aids, and four orderlies (usually). The system of management was different, the materials different or with different names—no luxuries—a limited supply of necessities and endless British Red tape to conform to—my wards were sick and as I look back on the six months spent at this work it seems like one continuous stream of days filled with anxiety as to how my men could be properly cared for by the people I had to it—and of an equally appalling number of nights filling the utmost dissatisfaction with what I had been able to accomplish—Fortunately, the walks over country were beautiful and our trips to adjoining townes—weekly sightseeing visits to old churches and their historically interesting places enlivened what would have been a dreary monotony. Yet with it all the men made it worthwhile.—the amicability, patience, appreciation, humour and cheeriness even in dark, cold, rainy, muddy weather made up for all the energy expended.

By November 1st I for one, was glad enough to have a chance to move in to a house for the winter.

My turn for night duty came around and [NAME-Illegible] kindly put me on as supervisor so the winter has passed quickly and pleasantly.

There have been time when the work has been exceedingly light and other times when it has been very heavy, but with it all—the time has flown till now our first year is up and I wonder “what comes next”. Of course none of us expected to remain even as long as this and many even now are longing to return. For myself, I am quite willing to do what is asked of me—Remain or return as it is thought best. It doesn’t matter as I have no plans, so there you are. The only comfort I can see in the work is, in a very small way we are helping someone make history.

Things are running very smoothly in spite of the many changes in our staff all the time. One loses all sense of the value of any individual over here. No one matters. There is a vacancy to be filled and the most convenient person is chosen rather the one fitted for it.

The appropriateness of the saying of one of the orderlies is markable—he said “ I came over here to do Laboratory work, so far I have done only Lavatory work.” (he’s a college graduate with a sense of humor so is not entirely misfit as he might otherwise be.)

I spent a very delightful two weeks leave in Nice and the change from the cold, snowy, northern France to tropical vegetation and warm sunshine was a shock. But best of all were the beds. I had forgotten how soft a bed could be—

Traveling is rather difficult at present and at times trying, such as when a fat Frenchwoman chose to take my hat (a new one) form my couchette and then sat on it. However things are really much better than most people are lead to believe so there is no use in criticizing even the fat Frenchwomen as it was an accident.

The country is very lovely here now—our gardens are full of flowers and the wild-flowers grow in abundance in numerous varieties. Evey kind of a hat flower you have ever seen in New York is duplicated in the woods and fields here. So one always has the feeling that one is gathering artificial rather than real flowers.

Every morning the birds are singing their most brilliant songs and nature looks so calm and placid it is difficult to believe such awful things as we could have happened within such a few miles of us. We had a small portion of the American Army brough to use the other night. Six patients, to be exact, one was an Englishman, one Irishman, one German, one Italian, and to New Zealanders. I thought what too good a joke to keep so I am handing it over to you.

I know the world has moved along very fast with you as well as with us. We have the Journal which tells us the big things and papers, clippings and letters bring in other news. Edna [ILLEGIBLE] has been most kind to me, writing me monthly and sending the Sunday Times.

I know Mrs. Hall has written you about the [ILLEGIBLE] and has told you all the official things I know you are interested in. Please remember me to Miss Stewart, Miss Goodrich, and Miss Crandace. I will try not to wait quite so long before writing again but you can see for yourself, I’ve done nothing to write you about. I have only succeeded in helping Miss Hall carry on.

Very Sincerely Yours,

Alice L Lake

Alice Lake’s First Page

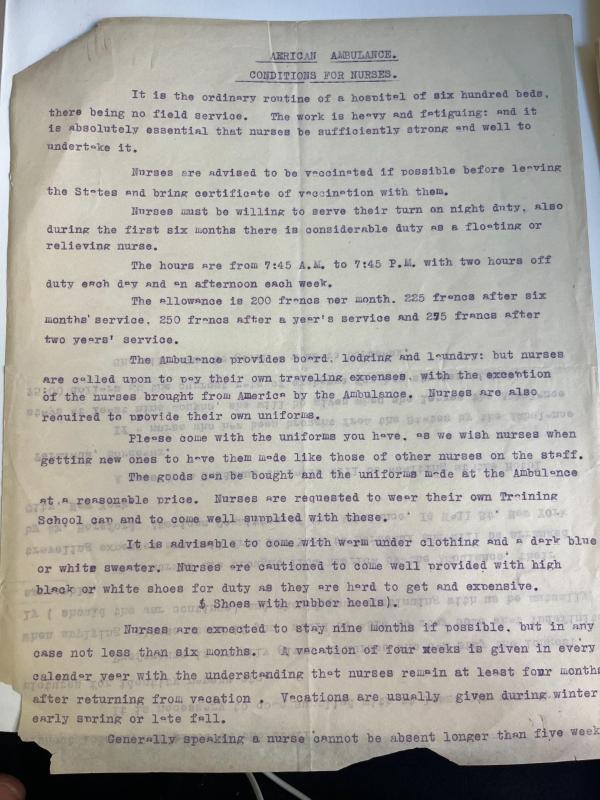

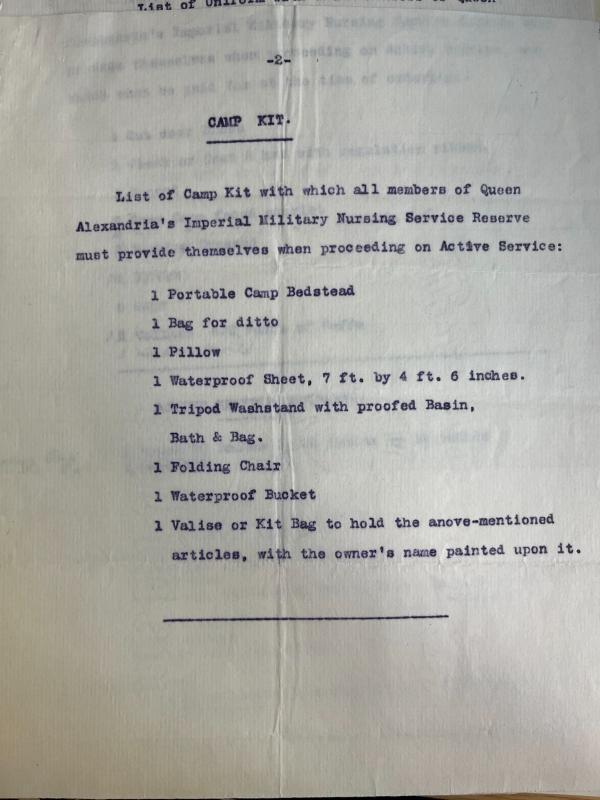

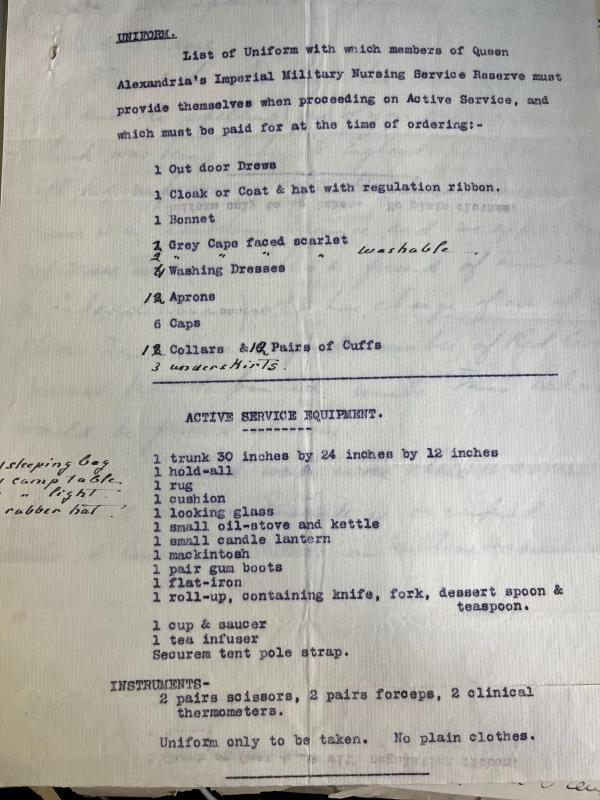

Below, I have included a small example of material from the folder:

Camp Kit

Uniforms

Gottesman Libraries and Teachers College Special Collections contains a very robust collection of material related to nursing, nutrition, and health sciences. Below is a brief list related to the general topic of nursing, and specifically about the role of nursing during wartime and emergencies:

Archives of the Department of Nursing

Finding themselves; the letters of an American Army chief nurse in a British hospital in France.

"Mademoiselle Miss" : letters from an American girl serving with the rank of lieutenant in a French army hospital at the front

Woman in the war : a bibliography

L'école sous les obus, pages vécues du martyre de Reims

Adventures of an army nurse in two wars

Report on the medico-military aspects of the European War from observations taken behind the allied armies in FranceThe life of Clara Barton : founder of the American Red cross

Role de la femme dans l'assistance aux blessés et malades militaires