“More Than Around the World”: Exploring the Travels of TC’s John and Margaret Norton

This blog post supplements the display in the Curiosity Cabinets on the third floor of the library, Backpack, Camelback, Outback, Wayback: Curious Accounts of Travel.

Teachers College and Travel: A Brief History

From the 1890s onward, Teachers College faculty members, administrators, and students have traveled around the world, both to learn about the educational systems of other countries and to establish educational initiatives abroad. This global outlook fostered an important exchange of ideas and connected educators in unprecedented ways. Institutes, centers, and programs instantiated by the College, such as the International Institute (1923-1938), saw faculty travel the globe as they studied the structure, organization, and implementation of educational systems in different countries. Faculty such as Paul Monroe, George S. Counts, William Heard Kilpatrick, William F. Russell, and Thomas Alexander furthered the study of education by visiting countries such as Bulgaria, China, Denmark, France, Germany, Iran, Iraq, the Philippines, the Soviet Union, and Sweden, among others. Their travels, studies, and support of scholars outside the United States allowed for serious examinations of international education as well as the implementation of projects in support of local educational initiatives. In the 1950s and 1960s, in his capacity as director of International Studies at Teachers College, Professor R. Freeman Butts oversaw and assisted in the creation and launch of the Teachers for East Africa (TEA) program, which recruited, selected, and educated American teachers for educational service and technical assistance to help increase the number of local qualified teachers in East Africa. Butts also oversaw the first Afghanistan Project, which focused on teacher education, and later included the development of a Faculty of Education for Kabul University, as well as the development and creation of curricula and textbooks for primary schools in the country.

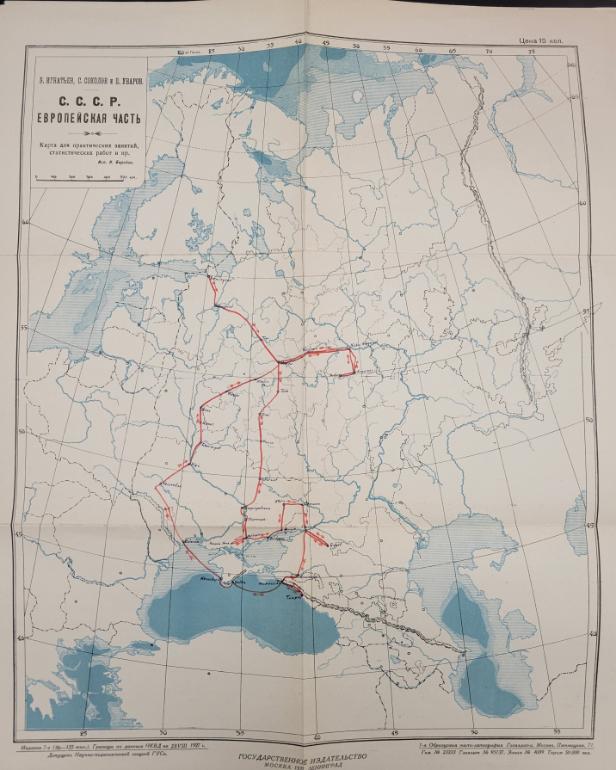

A map detailing Professor George S. Counts's trip through Russia. Printed in 1927, but with Counts' markings in red ink added later. William F. Rusell Papers, Series 1, Box 6, Folder: George Counts.

Individually, administrators and faculty embarked on journeys that took them far beyond the college’s walls. President of Teachers College from 1898 to 1927, James Earl Russell, undertook his doctoral research in pedagogy and psychology in Leipzig and Jena in the early 1890s. Arthur Wesley Dow, Professor of Art Education at Teachers College from 1904 to 1922, traveled to Kyoto, Japan in 1903 to learn traditional woodblock techniques and to lecture about the adoption of such techniques in Western art educational practice. Paul Monroe, Professor of Education and Director of the International Institute at Teachers College (1897-1935), embarked on several research trips, including visits to the Philippines, China, and Iraq. Mabel Carney, Professor of Rural Education, 1919-1941, traveled to Africa in 1926, in the hopes of learning about the educational systems on the continent. William F. Russell, President of Teachers College from 1927 to 1954, spent much of the 1930s and 1940s traveling around the American West and Europe, where he gave lectures, attended conferences, and networked with leaders in the field of education.

Students also participated in educational initiatives that involved international travel. Students from Professor Albert P. Cru’s 1931 French course traveled to Paris to learn directly about the culture and language (William F. Russell Papers, Box 5, “Cru, Albert P.”), while New College students, under the supervision of Thomas Alexander, planned and executed an educational trip to Berlin in 1933. Several field courses were also held in Latin America, Europe, and Asia throughout the 1930s under the direction of the International Institute (William F. Russell Papers, Box 9, “Foreign Field Courses”). Historical traces of this global outlook are present in the archives and Special Collections at Teachers College, and many of the narratives, documents, and memorabilia produced or acquired in the course of these travels are now in the curiosity cabinets as part of the display, Backpack, Camelback, Outback, Wayback: Curious Accounts of Travel.

Arrivals and Departures: the Curiosity Cabinets and the Archives

While collaborating with Senior Librarian, Jennifer Govan, to curate and prepare the newest display in the curiosity cabinets, several items immediately came to mind. Having updated an inventory of the archives in 2023 and having worked on finding aids for administrative and faculty papers, I turned to the correspondence, diaries, manuscripts, photographs, and other records of Teachers College’s well-traveled. Among these items were Paul Monroe and his wife Emma Monroe’s collection of travel photographs, itineraries, diaries, and cruise ship memorabilia; Mabel Carney’s African Letters; and the Nursing Education Archives’ reports concerning research trips to Japan and Russia. Also among these archival materials were V. Everit Macy’s postcard from Egypt; George S. Counts’s letters to William F. Russell concerning his travels in Russia; and Catherine “Fair” Scott Rose’s correspondence to Joan Hollobon, documenting Rose’s time as an administrator for Teacher Education in East Africa (TEEA). Additional curiosities included photographs taken by Professor John K. Norton and his wife, Margaret A. Norton during their 1937 globe-spanning journey; travel brochures from Europe; as well as cultural heritage objects, such as a Syrian medicine bowl from the Mary Adelaide Nutting Collection and Burmese prayer boards. These materials, and more, made their way into the curiosity cabinets. While the Special Collections stewards additional travel diaries from the Nortons and a handwritten account of William F. Russell’s 1946 trip to Europe, the condition of these items did not allow for them to be displayed.

Emma Monroe's Travel Diary. 1924. From the Paul Monroe Collection, Box 6, Memorabilia: Travel Journal, Diaries, Pictures, Bible. Item 14a.

Having perused many letters, diaries, and photographs from different archival collections, I was most intrigued and compelled by the travel accounts and travel-related items in John Kelley Norton’s Papers. John K. Norton was a Professor of Educational Administration at Teachers College from 1930 to 1958, and Chief of Party for the International Development Project in India from 1959 to 1962. Norton’s papers, while mostly covering his academic and administrative career at Teachers College, also include a series devoted to the diaries, correspondence, and academic work of his wife, Margaret May Alltucker Norton. Margaret Norton received her Ph.D. in education and economics from the University of California Berkeley in 1922. She taught courses on curriculum during the 1920s and early 1930s in the University of California system, and went on to author several articles and co-author two books with her husband. While John Norton is well-known for his work in educational administration and educational finance, the contributions of his wife, Margaret, are less known. John K. Norton’s collection reveals that Margaret Norton was more than a supportive wife of a renowned academic; she was a chronicler and a collector. She meticulously documented the history of her and her husband’s work, their travels, and the lives of their children. Her presence in John K. Norton’s archive is profound, and in many instances, cannot be separated from his. Nowhere in Norton’s collection is this presence more apparent than in the travel accounts from Series 10: Personal and Family Papers, 1901-1980 and Series 11: Margaret Alltucker Norton, 1921-1978.

More than Around the World: Reading the Nortons’ Travel Texts

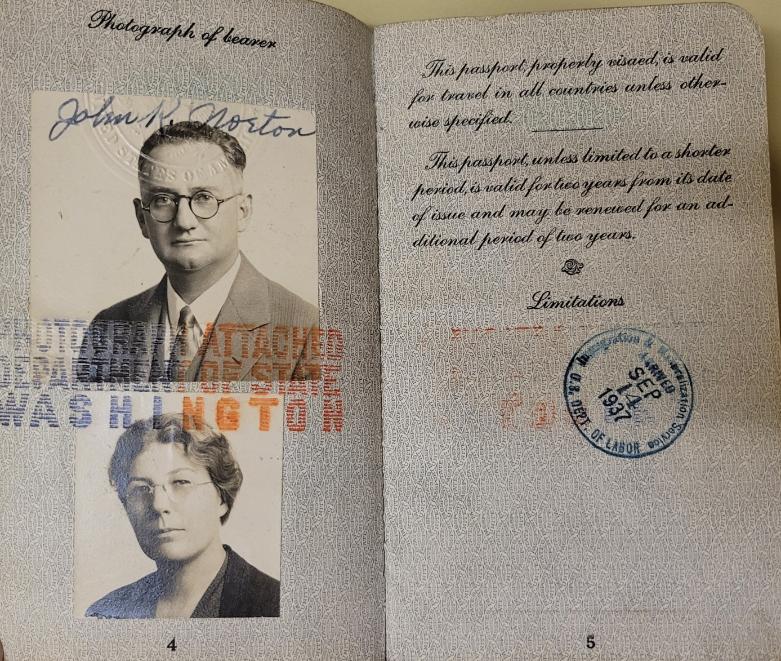

From December of 1936 to September of 1937, John and Margaret Norton undertook an international trip that encompassed Egypt, India, China, Indonesia, Japan, the Philippines, Russia, Ukraine, Georgia, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Germany. Partly traveling to gain an understanding of the educational systems and movements developing outside the United States, and partly traveling for leisure and cultural enrichment, the Nortons journeyed across 35,000 miles by steamship, train, and automobile. From their travels, they produced two accounts, accompanied by hundreds of photographs. The most polished account is one the couple co-authored: an unpublished manuscript detailing observations and insights gained on their travels. In More than Around the World: Excerpts from Letters Written Home and Notes Made on a 35,000 Mile Journey in 1936-’37 (John K. Norton Papers, Series 10, box 15, Folder 1 & Folder 2), John and Margaret Norton collaboratively wrote about their experiences. Primarily, the manuscript focuses on their time in India, China, and the U.S.S.R. The typed manuscript contains several engaging narratives and rich descriptions of the people they meet, the sites they see, and the things they learn. However, More than Around the World, when discussing educational systems, or providing political and economic commentary, reads like a digest or report and is anthropological in its tone.

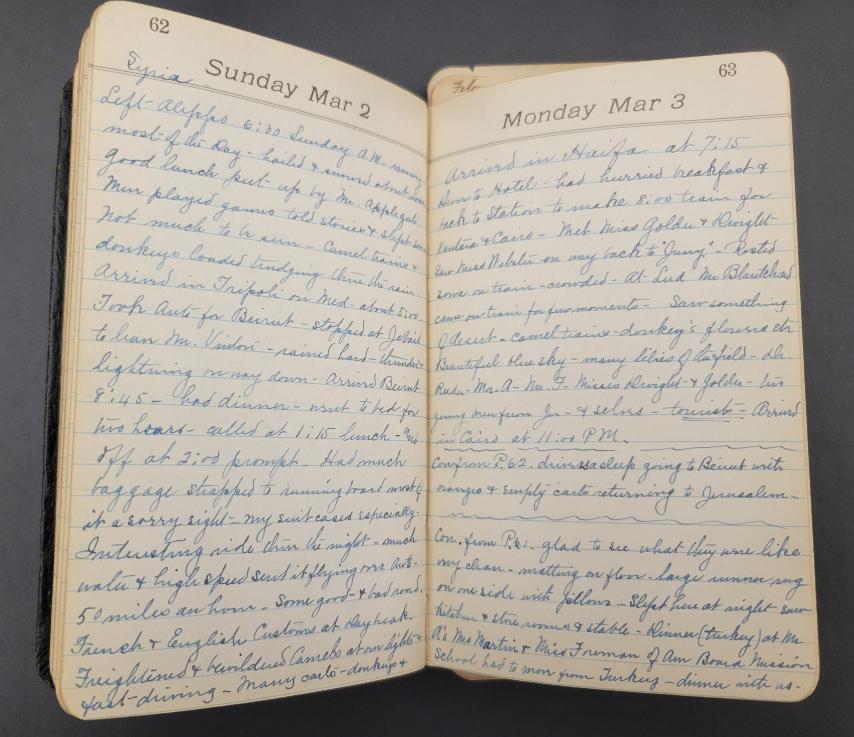

On the other hand, a second account of the same journey exists in John K. Norton’s archive that offers a more personal narrative of the couple’s travels. This account comes in the form of a travel diary written by Margaret A. Norton (Series 11, box 14). Margaret Norton’s diary serves as a parallel text, capturing moments of intercultural exchange, offering striking descriptions, and recording fleeting observations that are not present in the typed manuscript. Margaret Norton’s diary encompasses entries on every locale the couple visited, including sites excluded from More than Around the World. Her diary devotes over thirty pages to the Nortons’ time in Java, Bali, and Burma (now known as Indonesia and Myanmar), which do not feature in the co-authored manuscript. Her diary entries also offer more detailed descriptions of her and her husband’s time in Egypt, Japan, and the U.S.S.R. These descriptions focus more on typical travel activities, such as visits to temples, museums, and other important landmarks; whereas the typed manuscript focuses more on interviews with educational leaders, observations about infrastructure and government, as well as analysis of educational movements and projects. Her diary fills the gaps present in More than Around the World.

Passport of John and Margaret Norton. John Kelley Norton Papers, Box 15, folder: "Passports -- J.K.N. + M.A.N., 1937-59".

Most intriguing to me, in both accounts, were the Nortons’ descriptions of their travels in Egypt, India, Indonesia, and China. These accounts were compelling, in part, because they offered observations and critiques concerning the failures of Western influence, and the pitfalls of colonial rule (especially in Egypt and India). On the other hand, their descriptions of cultural heritage sites and the natural beauty of the countries visited were among the most striking.

John and Margaret Norton set sail for Europe at the close of 1936. While the Second World War was less than three years away, tensions were mounting around the globe, due in part to the effects of the Great Depression, the rise of authoritarian governments, and increasing unrest and anticolonial movements in British, Dutch, and French colonies. The steamship on which the Nortons sailed charged towards Europe, bypassing Spain due to the Spanish Civil War. However, the Nortons stopped briefly in Italy, where they witnessed “Mussolini’s hunger for more land,” and the intensity of his regime’s propaganda (Folder 1, p. 3). From Italy, they sailed on to Egypt, whose countryside was full of “palms, orange groves, water wheels, fields of sugar cane, rice and wheat” (M. A. Norton, 1937). But more interesting to the Nortons than Egypt’s countryside or its pyramids and tombs, were Egypt’s “people and their life” (Folder 1, p. 3). Their local guide, Solomon, took the Nortons to see his village, to observe infrastructural projects carried out by the British colonial government, to tour a local school, and to sample local cuisine (M. A. Norton, 1937). Both in More than Around the World, and in Margaret Norton’s diary, the same sentiments are expressed: the Egyptian people were welcoming, the food was delicious, and the ancient sites were fascinating. And while the Nortons commended the British government’s efforts to improve infrastructure and education in Egypt as admirable, Margaret Norton critiques colonial rule. While the British government had created a sugar mill and transformed patches of desert into arable land, “Nothing … had been done to alleviate the wretched conditions under which the natives lived” (M.A. Norton, 1937). Her statement highlights the ways such projects were designed to profit the empire, not improve the material conditions of the people living under such rule.

After two weeks in Egypt, John and Margaret Norton sailed South into the Red Sea, making their way to the Indian Ocean. Their next stop was India, where they spent a month of their travels. In India, they toured local schools and universities, visited temples, hiked the mountains in Darjeeling, and toured local towns. Both John and Margaret Norton describe India as a “land of contrasts” and “extremes” (Folder 1; M. A. Norton, 1937). For the Nortons, the combination of different geographies, religions, languages, and economic disparities seemed to create a land and people at odds. This was apparent in the schools they observed. In February of 1937, when they visited Banaras Hindu University, they met with a young assistant librarian named D. Subrahmanyam, who Margaret Norton described as “a brilliant young Hindu much in sympathy with the ‘Congress,’ the radical political group who want independence from Britain,” (M. A. Norton, 1937). The Nortons, in talking with Subrahmanyam, and other students and professors, came to learn that the bachelor’s degree involved “a curriculum developed for Britain rather than India” (Folder 1, p. 4, [PDF 8]). While students studied Shakespeare and English grammar, the Nortons, after speaking to students, teachers, and locals, thought a study of local histories, literature, and practical arts would benefit India’s future generations.

A photograph taken in India by John or Margaret Norton. Photograph. circa 1937. John K. Norton Papers. India. Box 24.

While their observations of British educational practices in the Indian school system were critical, they felt an affinity for the Indian people. They enjoyed visiting Ushagram, where they were “entertained [by] witty folk dances” performed by local students (M. A. Norton, 1937), and they enjoyed visiting cultural heritage sites, such as the Taj Mahal. One of the “high points” of their travels in India was their time in Darjeeling and West Bengal. In both Margaret Norton’s diary and in the manuscript More than Around the World, John and Margaret Norton describe their ascent up Tiger Hill. In Margaret Norton’s February 24th diary entry, she writes of their first attempt:

“The moon lighted our way up the steep climb to the top. Bundled up in many clothes, we arrived panting and scraped the frost off the seat in the little tower and settled down to watch the sunrise. Everything was most auspicious for a grand view of the snow peaks — until heavy clouds arose from the valley below … clouds, turned into fire opals by the rising sun and the pass into Tibet.” (M. A. Norton, 1937).

Her diary entry highlights the physical exertion, the cold temperatures, and the reward of the climb, despite the fact that the clouds obscured their view of the surrounding hills and valleys. Her images are striking: turning the landscape into a rich and jeweled spectacle. The account from the co-authored manuscript, however, focuses more on the landscape’s scale:

“Three mornings straight the Nortons rose at 4 A.M. and ascended 1,500 feet to the top of Tiger Hill, a little eminence of a mere 8,500 feet. Here they hoped to rise above the mists and clouds and view the Himalayan Range at sunrise in all its white majesty.

On the third morning, the gods of weather were kind. From our eirie [sic] perch, we surveyed the towering peaks of the highest mountains in the world. Kanchenjunga to the north in Sikkim with its height of more than 28,000 feet, dominated the unforgettable panorama. To the west, stretched the jagged peaks of Bhutan and Tibet, twenty and twenty-five thousand feet in height. Far to the west, we could clearly see the triangular gash which constitutes the principal pass into Tibet, more than 17,000 feet above sea level. Then the clouds began to break in the northeast in distant Nepal. One of the sister peaks of Everest came into view, and then Mt. Everest itself, more than a hundred miles away, but so clear that with the aid of our binoculars we could plainly make out some of the markings on its tempest-swept slopes.” (Folder 1, p. 27 [31 in PDF]).

Both descriptions are romantic and picturesque, but in More than Around the World the Nortons are diminished by the landscape. The switch in perspective, from third person to first person plural, suggests that they are trying to assert a sense of agency over the landscape. They can control what they see through man made binoculars, but they cannot control the sheer presence of the mountains they attempt to climb.

A photograph taken in India by John or Margaret Norton. Photograph. circa 1937. John K. Norton Papers. India. Box 24.

From India, the Nortons sailed to Burma (now Myanmar), Malaysia as well as modern-day Indonesia. These destinations are not recorded in the pages of More than Around the World, but Margaret Norton’s diary addresses this portion of the couple’s trip. This part of the Nortons’ trip focused on school visits, museum outings, temple visits, and tours of factories. In Johor, they “had lunch at a waterfall in the jungle” and later visited a rubber plant and pineapple cannery (M. A. Norton, 1937). In Indonesia, local guides from Java and Bali were able to interpret for the Nortons and direct their tour. Through the knowledge of their guides, the Nortons were able to visit several street markets and sightsee culturally important locales. They visited “the old walled city, saw the Sultan’s Palace, the Water Castle, Batik Works, Brass foundry – Arts + Crafts exhibit and attended a Shadow play” (M. A. Norton, 1937). They also were able to visit the Prambanan Temples. In Bali, their guide took them to see traditional Balinese dancers, and led them to Pura Goa Lawah, as well as temples in Denpasar. Margaret Norton’s diary describes a night visit to one such temple: “Never have [we] seen anything more picturesque than this lovely beach in the moonlight, fringed with coconut palms, scores of children playing by the water’s edge – and women bearing offerings to the temple” [M. A. Norton, 1937). Their guide’s expertise allowed the Nortons to gain deeper insight into the lives of Javanese and Balinese people living under Dutch colonial rule, and allowed them to experience the culture more authentically than they would have with a non-local guide. But their stay in Indonesia was relatively short, and they went on to the Philippines and China, where they stayed for six weeks.

Photograph of Margaret Norton at the Prambanan Temple Complex. Photograph. circa 1937. John K. Norton Papers. Java, Bali, Burma. Box 24

Balinese Dancers. Photograph. circa 1937. John K. Norton Papers. Java, Bali, Burma. Box 24

They first stopped in Hong Kong, captivated by the beauty of Kowloon. Their manuscript dubs it the “Riviera of the Orient” (Folder 1, p. 7 [38 in PDF]). Margaret Norton’s diary accounts for their first night in the neighborhood, noting that at once all the lights “came out, like so many diamonds set in ebony” (M. A. Norton, 1937). From Hong Kong, the Nortons traveled to Guangdong, where they met with Teachers College alumni, Yam Tong Hoh and Ye Shen. Yam Tong Hoh was the principal of the True Light Middle School and offered the Nortons a tour of the campus and an overview of the school’s curriculum. Ye Shen invited the Nortons to an elaborate dinner party. The food in Guangdong was among the Nortons’ favorite, and they note that the province “deserves its world-wide reputation for delicious food” (Folder 1, p. 1 [52 in PDF]). They go on to describe the dinner and its courses over the next three pages, testifying as to the quality and flavor of each dish, especially the fried prawns. The Nortons then head further inland by train, to explore other parts of China.

They headed to Shandong province, where they ascended Mount Tai. The couple hired sedan chairs and bearers, as the climb, according to their guidebook, was incredibly steep. As they walked or were carried up the mountain, they reflected on the travelers who made the same trek before them, remarking: “This path up the mountain has been trodden by the feet of countless pilgrims” [(Folder 1, p. 2 [74 in PDF]). The Nortons count themselves among a community of travelers who came to pay their respects to the sacred mountain. When they ascended to the temple of Bixia Yuanjun, however, the Nortons became a distracting spectacle to devout temple-goers. They transform into objects of curiosity and thus write of the experience as if disembodied: “The camera of the man came in for much open-mouthed and wide-eyed inspection, while the fully grown feet and particularly the sizable legs of the woman, along with the heels on her shoes, became the objects of both visual and tactical inspection” (Folder 1, pgs. 5-6 [77-78 in PDF]). In this scene, the Nortons fall into old tropes of travel writing: as foreigners, they become subject to the penetrating gaze of the Other while also becoming Other. Their presence and their bodies are sites of cultural clash while their possessions offer the possibility of intercultural exchange.

Photograph of Margaret Norton in a sedan with sedan bearers. Writing on the back of the photograph notes, "Four 'bearers' carried mother to the top of the scared mountain, Tai Shan, but three other 'bearers' wanted to be in the picture too." Circa 1937. John K. Norton Papers. China. Box 24

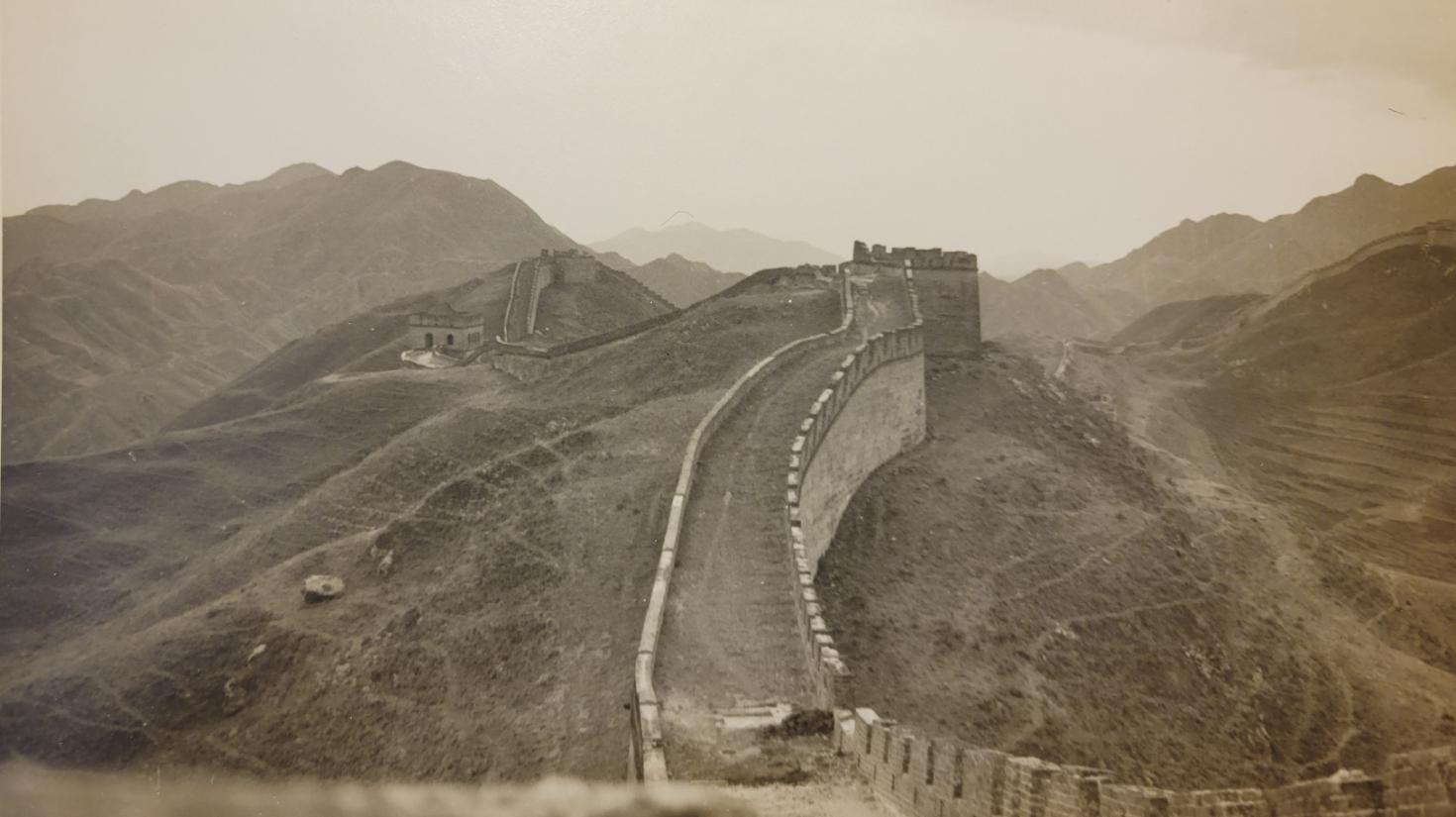

While their climb of Mount Tai was memorable, the Nortons were the most affected by their tour of the Great Wall of China. The experience, as the Nortons describe it, was almost spiritual. They connect to a past that is not theirs, but feel profoundly wrapped up in its beauty and its history. While it is often difficult to tell which of the Nortons authored More than Around the World, the section on the Great Wall is clearly Margaret Norton’s writing, as she refers to John Norton in third person and herself in first person. Her account of her experience in visiting the Great Wall of China is romantic, transcendent, and contemplative:

“I gazed for miles, first in one direction, and then in another – toward the vast Gobi Desert, toward Tibet, toward Manchuria and out to Mongolia … Before me are five brown ridges of great hills, bare except for occasional huge rocks, protruding like grey bones and faint traces of new grass, giving a green tinge to the landscape. Back of these five ridges rise high mountains . The Great Wall dips down into the valleys, climbs over the backs of the five hills and is lost to view as it rises 4,000 feet and tops the distant mount range. Sine the Wall follows the circuitous route of the contours of this rugged country, and due to the fact that there are many subsidiary walls, loops, and protecting arms that surround the Wall proper in mountain passes, its length is stretched to a tremendous distance – 2500 miles, according to my guide book.

To the left, in the valley below me, I see the many tunnelled [sic] railway as it winds its way out of Manchuria. Further up on the hill side is a great flock of wild goats, pure white except for their black heads with striped faces and black legs and tails. To the right, far in the distance, stretching out for miles is the Gobi Desert, brown and dry with only an occasional tree. Out towards Manchuria goes a great caravan of heavily laden camels – strong young ones, each carrying 800 pounds, tired old ones carrying only 500. Picturesque, swarthy-faced donkey drivers with heavy brown home-spun blankets, folded and flung over one shoulder, dressed in old blue cotton jackets and coarse blue cotton pantaloons tucked into well-worn shoes, that should have been much more substantial considering the jagged rocky road, prodded and urged on their large, tough, sure-footed donkeys on whose pack saddles were strapped great boxes of oil and gasoline in transit to distant Mongolia. The vastness and the wildness of the landscape, the romance of the Great Wall and the mystery of where it leads as it disappears over the distant range, the hardihood and adventurous spirit of the drivers of the picturesque camel and donkey trains, stir my vagabond spirit, I want to travel with them and trace out the Great Wall for a hundred miles or more.

Instead, I did what I was scheduled to do. I walked back to the railroad station in time to catch the train that was waiting to take back to Nankow Pass.” (Folder 1, p. 3-4) [91-92 in PDF]

Margaret Norton’s description reveals a desire for further travel and for adventure, one not burdened by meticulously planned and designed tours. Her recollection almost gives way to fantasy, but in the end, she remembers her role as a tourist, bound to the timetable and per-planned routes.

Photograph of the Great Wall of China, circa 1937. John K. Norton Papers. China. Box 24.

After their time in China, the Nortons traveled to Japan, to Russia, and then towards Europe. Their journey in Russia is well-documented in More than Around the World, while Margaret Norton’s diary records the stops in Japan, Scandinavia, and Germany. While these entries are interesting and insightful for what they reveal about the educational and economic systems in the country, the Nortons’ accounts of India and China are among their most stunning. When they returned to New York in the fall of 1937 – back to the Halls of Teachers College and the responsibilities of teaching and writing – they began working on lectures and articles inspired by their long journey. At the Graduate Club’s Coffee Hour on October 17th, 1937, John K. Norton gave an address at 6:30 PM in the Grace Dodge room, “Thirty Thousand Miles of Going Places and Seeing Things.” Margaret. Norton was also at the lecture (TC3 J52 – Teachers College Official Bulletin, vol. 1-5, 1936-1940). The couple later wrote an article about the educational systems in each country they visited for the American Association of University Women.

Photograph taken while in the U.S.S.R., circa 1937. John K. Norton Papers. U.S.S.R. Box 24.

The Nortons' travel accounts are just two of many in the archives and Special Collections. Their photographs, manuscripts, passports, and itineraries mark attitudes and perspectives of their time, as do other travel accounts. While the Nortons' writings about their global journey were not published, their insights, observations, and sentiments went on to inspire the educational work carried out at Teachers College. John K. Norton was involved in domestic and international projects concerning education for the rest of his career, and Margaret Norton worked to support those efforts. The legacy lives on, through the International and Comparative Education Department and the Jaffe Peace Corps Fellows Program.

References

Norton, J. K. and Norton, M. A. (1937). More than Around the World: Excerpts from Letters Written Home and Notes Made on a 35,000 Mile Journey in 1936-’37 [Unpublished manuscript]. John K. Norton Papers, (RG 28: 830222), Series 10: Personal and Family Papers, 1901-1980, Box 15, folder 1 and folder 2. Gottesman Libraries Special Collections and Archives, Teachers College, Columbia University, N.Y.

Norton, M. A. (1937) [Unpublished diary]. John K. Norton Papers, (RG 28: 830222), Series 11: Margaret Alltucker Norton, 1921-1978, Box 14.. Gottesman Libraries Special Collections and Archives, Teachers College, Columbia University, N.Y.