Dear Family: Lt. Aileen Hogan's Correspondence from World War II (1942-1945)

Letters from the 2nd General Hospital during the European Theatre of Operations

Early in the Fall Term of 2025 Jennifer Ulrich, the Archivist and Special Collections Librarian at Columbia University Medical Center, reached out in regards to any copyright information or documentation Gottesman Libraries might have about a collection of 417 letters written by Lt. Aileen Hogan (1899-1981)—who later went on to attend Teachers College (1948)—during her time as a nurse with the Army Nursing Corp in the European Theatre of Operations in World War 2, and later transcribed by Ruth Lee.

Two weeks later, I was happy to report back that not only did we have the original correspondence intact, but our records—dating back to the tenure of David Ment as Head of Special Collections—indicated that Lee had expressed that her work could and should be used at will.

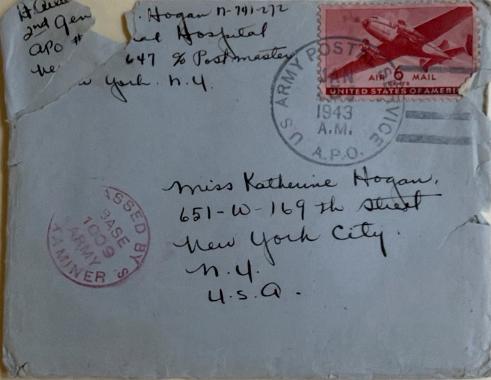

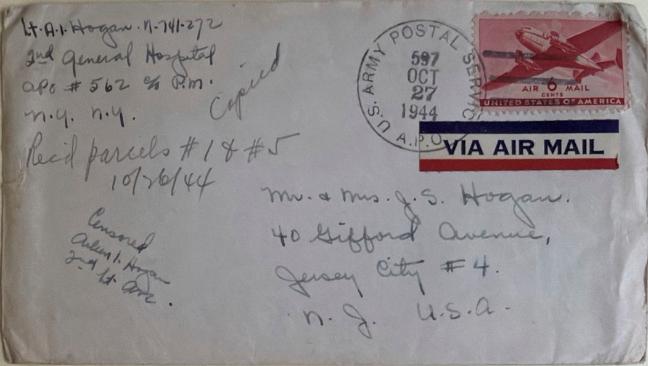

As often happens during the (re)discovery of a collection, we performed a light re-processing, including a modest amount of preservation work and a basic inventory. As I unwrapped bundles of letters, extracted correspondence from envelops and flattened each of the 417 letters, my curiosity piqued.

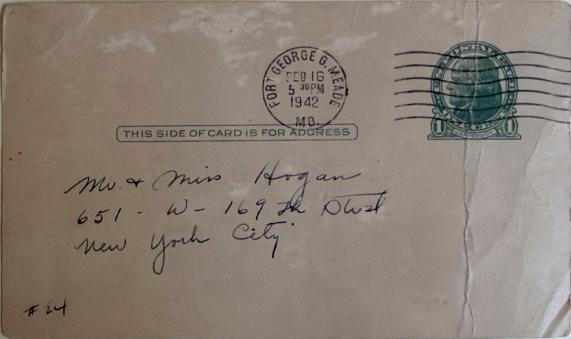

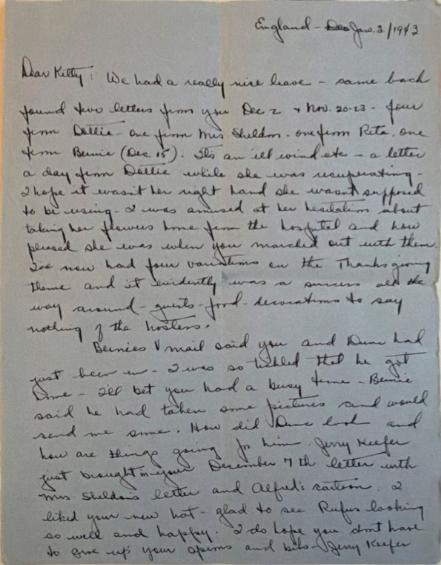

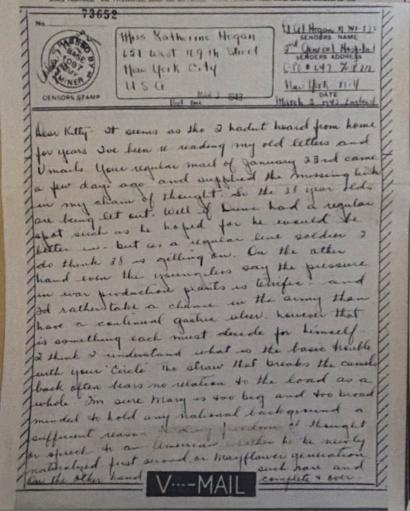

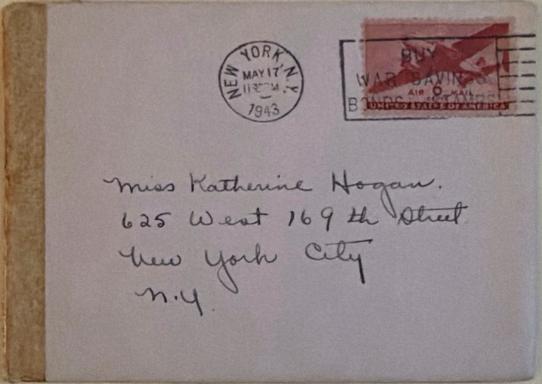

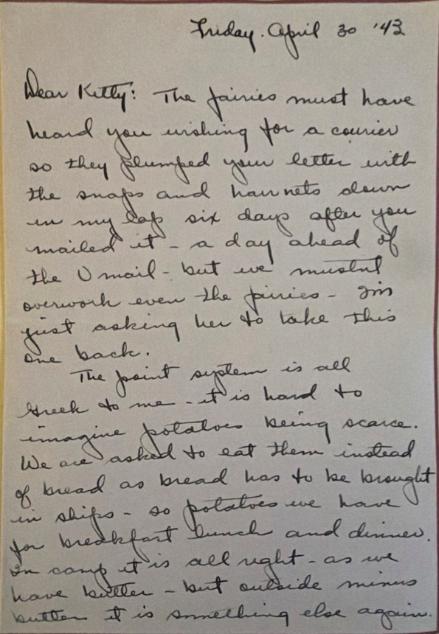

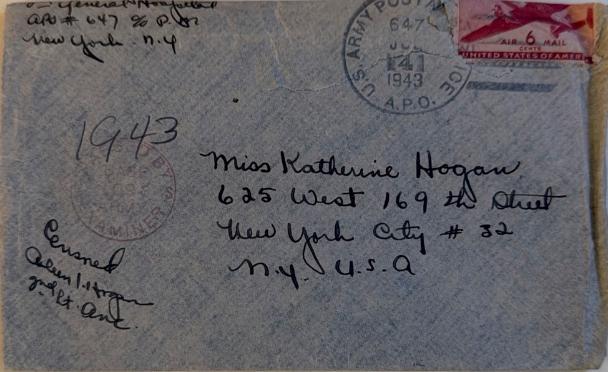

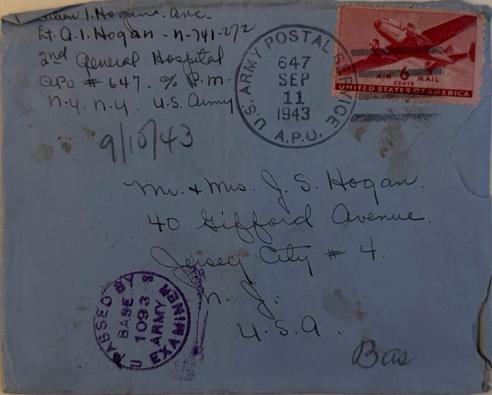

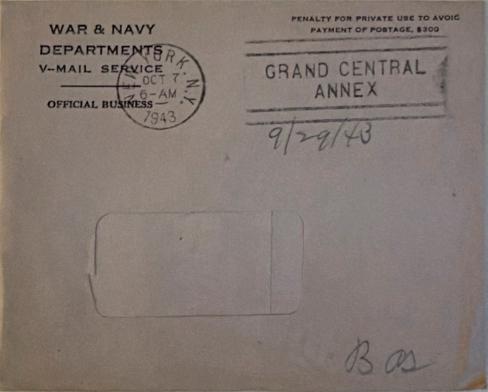

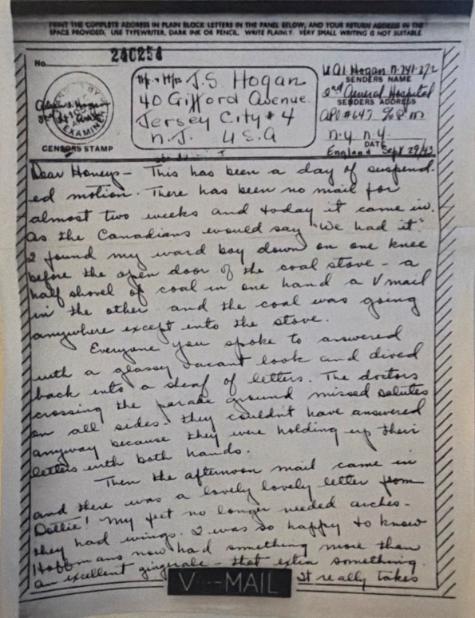

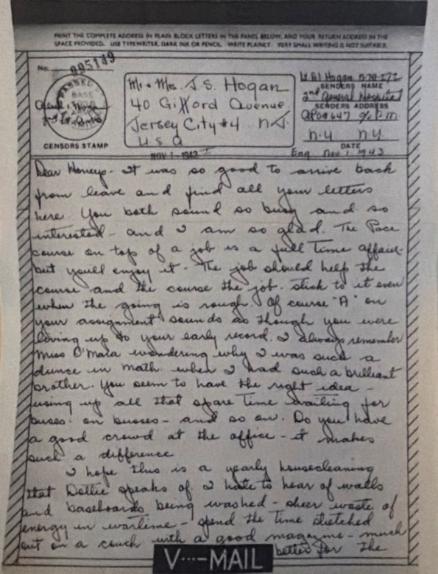

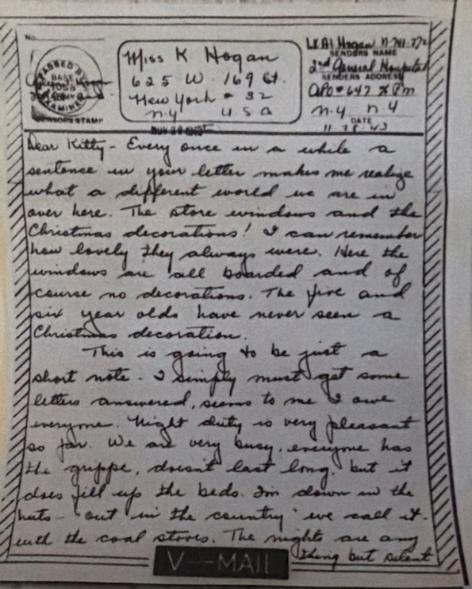

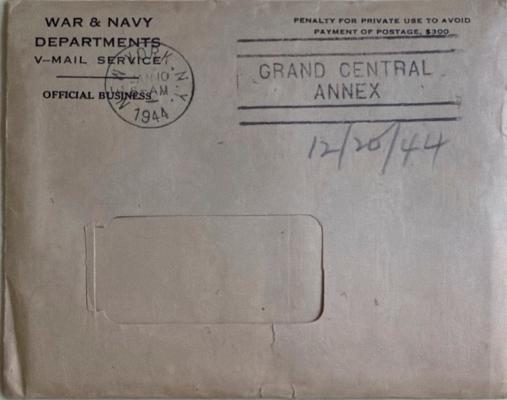

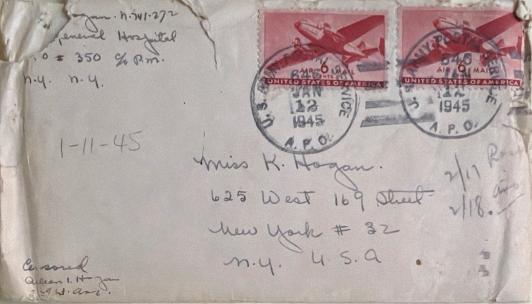

First to catch my attention were the envelopes. As ephemera, each was unique in some ways—whether by type (V-Mail or Airmail), postage (or lack thereof) and postmark, address, and condition. Though nearly all were either stamped with “Assessed by Examiner” or had “Censored” written in an exacting script with pencil.

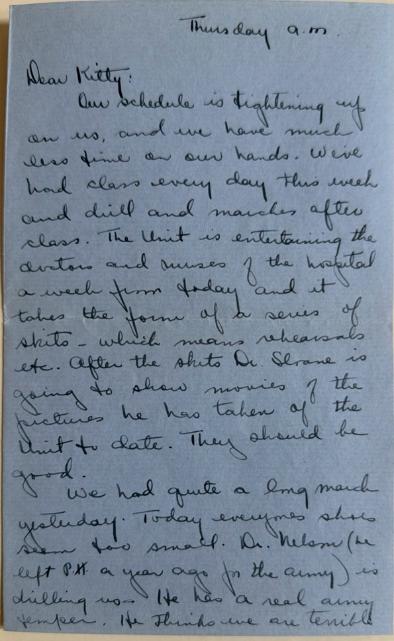

Each letter was almost unanimously addressed to “My Family”, “Dear Honey’s”, or her sister Katherine, though more often and affectionally referred to as “Kitty”. While the letters flattened, I began to read through Ruth Lee’s transcriptions and following Hogan’s journey from New York City to Ft. Meade, Maryland, eventually all the way to Marseille, France and back again.

At 41, Lt. Aileen Hogan was one of the older nurses in the 2nd General Hospital, at least by her own account, often remarking on general aches and pains and her involvement (or absence) in travel leave to London and beyond or the late-night antics comprised of numerous parties that took place under the blacked-out skies of England in 1942.

Her age, however, did not hinder her from participating in drills involving gas masks, field hikes, tent bivouacs, air raids, rationing, shortages, night shifts, or working in evacuation hospitals close to the front lines in Belgium. In fact, in a letter to Aileen’s brother, Major William Province makes a point to write “I think your sister is the finest medical nurse I have ever worked with…” in reference to her time a charge of the Communicable Disease Service in France.

Though censored, she writes with a sense of detail and clarity that precludes the need to read into subtext or between the lines. She is on equal footing describing medical procedures or details of administrative procedures as she is discussing the natural dichotomy between beauty and death, sublimity and terror, the mundane and the exceptional. Her correspondence reflects not only her own personal and professional relationship to the European Theatre of Operations during World War II, but also her reactions—while abroad—to domestic turmoil such as the coal miners’ and rubber strikes of 1943 as we well as the presidential election of 1944.

The letters provide researchers and readers a palimpsest of an individual’s singular experience over the fabric of one of the most impactful events of the 20th century. Framing Lt. Hogan’s letters within the context of the timeline of major moments in WWII, we come to understand that the letters offer a phenomenological foundation of the collective historic event. With this in mind, we sought to layer Hogan’s letters within the overarching timeline of the ETO in order to provide contextual borders, as well as a brief geographical plot of Hogan’s travels. Additionally, I have included portions of transcripts of the letters that seemed impactful to Lt. Aileen Hogan’s story as a nurse attached to the 2nd General Hospital of the Army Nursing Corp.

For additional information please see Columbia University Medical Center Special Collections, the World War 2 U.S. Medical Research Centre, or book a consultation at Gottesman Libraries Special Collections

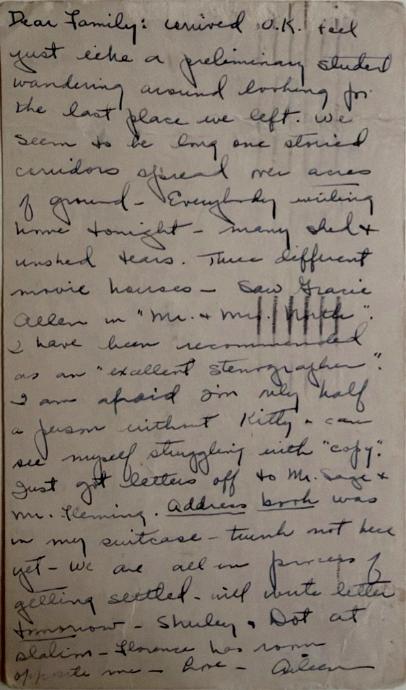

2/15/1942

Dear Family: Feel just like a preliminary student wandering around, looking for the last place we left. We (the hospital) seem to be long one-storied corridors spread over acres of ground. Everybody writing home tonight—many shed and unshed tears. Three different movies houses—saw Gracie Allen in “Mr. and Mrs. North”. I have been recommended as an “excellent stenographer” …Just got letters off to Mr. Sage and Mr. Fleming (Trustees of Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital). Address book was in my suitcase—trunk not here yet—we are all in the process of getting settled…

03/26/1942

Yesterday we fell in and marched...3 miles to the gas shelter, a house about the size of a room, built on the side of a hill. The nurses went first in full equipment, capes, caps, and gas masks. We were to file in in single file and leave by the emergency exit. We found the emergency exit was a wooden boxed-in tunnel about the size of a dumbwaiter and 14 feet long. We had to crawl through on all fours and come out the other side of the hill. The little ones made it easily. The medium ones like myself didn’t have much trouble, but I imagine it was something of an ordeal for the ones built on Amazonian lines. Then we lined up to watch the doctors come through. They had to wear their gas masks and push the door open at the end of the tunnel with their heads. The Colonel in charge of the post was the biggest, 6’2”, about 250? He made it with a smile but I think it was a tight squeeze…

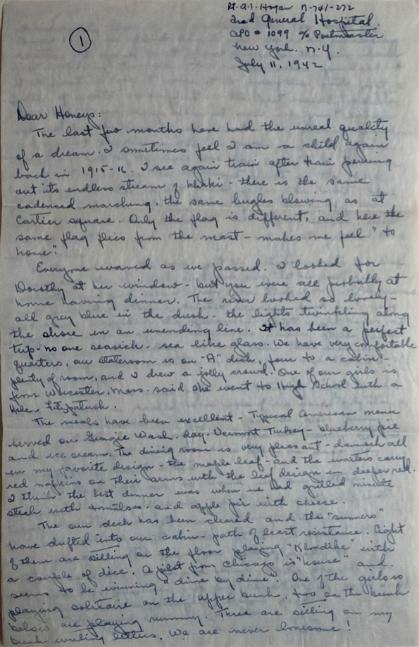

7/11/1942

(parenthetical's added by Ruth Lee during original transcription) This letter sets the tone regarding content for the rest of the correspondence in terms of what the censors will allow and will not

Dear Honeys: The last two months have had the unreal quality of a dream. I sometimes feel I am a child again, back in 1915-16. I see again train after train pouring out its endless stream of khaki. There is the same cadenced marching, the same bugles blowing as at Cartier Square (Ottawa). Only the flag is different and here the same flag flies from our mast (Canadian). Everyone waved as we passed (New York harbor). I looked for Dorothy at her window, but you were all probably at home having dinner. The river (Hudson) looked so lovely, all gray blue in the dusk, the lights twinkling along the shore in a never-ending line…the meals have been excellent, typical American menu served on Georgie Washington Day (?4th of July), Vermont turkey, blueberry pie and ice cream. The dining room is very pleasant, damask all in my favorite design, the maple leaf, and the waiters carry red napkins on their arms with the maple leaf in deeper red. I think the best dinner was when we had grilled steaks and apple pie with cheese. The sun deck has been cleared and the “summers” have drifted into our cabin, path of least resistance. Eight of them are sitting on the floor playing “Klondike” with a couple of dice. A pilot from Chicago is “house” and seems to be winning “dime by dime”. One of the girls is playing solitaire on the upper bunk, two on the bunk below are playing rummy. Three are sitting on my bunk writing letters. We are never lonesome! It has really been a marvelous trip. Too bad the Censor keeps us dumb about all the most interesting events. We spend most of our time on the sundeck watching the ocean. No matter where you look it is different. I love it when it is navy blue with just a froth of white to keep it in the best naval tradition. There have been days when it has been running in great raisin colored swells, each swell lined with shining aquamarine and joined together with a feathery white plume. Two of us sat by the rail one day and tried to make the third of us see the amethyst glints in the dark green swells that swept away from the boat. She just couldn’t see them. Finally we took off our glasses and we couldn’t see them either!...I think we are to in our letters unsealed the day before we land. It is quite different trying to write and yet say nothing. By the end of the way we’ll be past masters at it. At present it does not come easy. The gang are getting ready to go for a stroll on the deck. You should see us, slacks, topcoats, tin hats and life preservers. We are something to see. I add sunglasses and a handful of lemon drops…

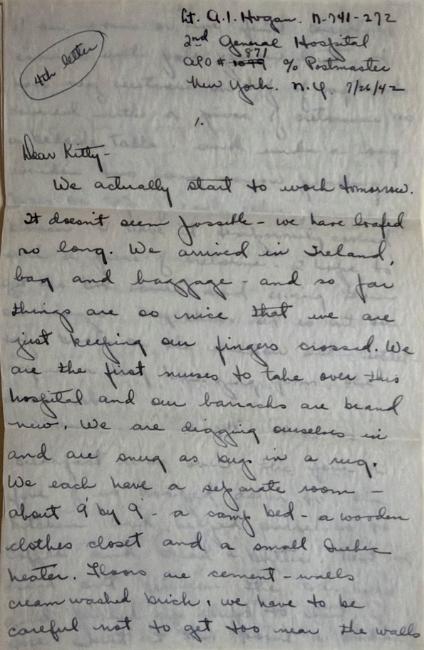

7/26/1942[1]

…the last good nights had faded on the midnight air when the air raid alarm sounded. You should have seen us getting dressed in the dark and parading out complete with blanket, helmet and flashlight. It was one of those clear moonlit nights—navy blue sky—every star in place—clear and cold. As the air raid wasn’t in our immediate vicinity we stayed outside but did not go into the shelter. We could see nothing, but way up we could hear the interrupted Brrrr-Brrr-Brrrr of the German planes and the steady whirr of our own planes. The motors are different. You can’t mistake them. We were in no danger but it was our first alarm…

9/5/1942

…It is really marvelous what they can do with practically nothing but a few saws, a pen knife and a little sand paper. We have several artists and they have painted murals on the great squares of paper that form the wall panels and they are teaching any of the boys that show any inclination. Some are making clay figures, footstools, coat hangers, swinging picture frames. Leather work and basketry are the latest. Getting material is the difficulty. Anything not war material is hard to find…Our lates project is dolls for Christmas for evacuee children. Tomorrow we are trying to a pattern for the dulls and “butter muslin”. We don’t even know what it is. The boys are going to make and stuff the dolls and we are going to dress them. They are making wooden wheelbarrows and pull carts, doll houses and doll furniture. All our colored toothbrush handles have been asked for and the boys make rings from them…

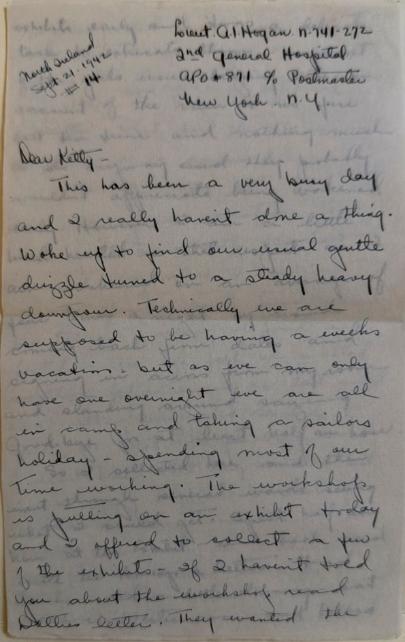

9/21/1942

…The Workshop is putting on an exhibit and I have been running all over the quarters and the Hospital trying to part the owners from the exhibits. The Chaplain is a carpenter by hobby and Major Sheldon can do considerable work with string and small hand looms. We found much talent, several very fine artists, commercial sketchers, men who can whittle and men who really know carpentry. The Major spends all his time finding supplies. You just can’t even get a piece of string. The Chaplain spends his time and most of his money getting tools for the carpentry shop. The men have produced some really lovely things, inlaid trays, and scenic wood pictures, jewel cases, hope chests, tables, desks, book ends. They have made all models of airplanes. Some are so good that the officers are using them for demonstration purposes in their classroom work. One boy made a red signet ring (toothbrush handle), put a small picture of his girl friend on the signet and sealed it with a translucent piece of toothbrush handle. They have used shillings to make really good looking silver rings. They have made inlaid chess boards and whittled the men out of blocks of wood. The water colors are lovely…The boys love to teach each other and the whole thing is quite a success. The exhibit is to advertise and spread the idea and maybe get a little official help regarding material, etc…

1/3/1943

“Ellen Dodge took me out to dinner one night with two very young officers from the famous Polish Black Tank Bn[2]…when the Poles found out that I had never been out in a London Blackout, they decided immediately that we would tour London on foot. They are very picturesque, black boots, black berets, black leather trench coats, and they are very interesting. They have the reputation of being the fiercest fighters in Europe. One was in Athens when it fell, one in Paris.”

3/3/1943

“They [English nurses from the “tropics”] had never seen a frostbite patient and were quite interested. We have them. I suppose they take off their gloves for a minute to fix or change an oxygen mask or something and it only takes a minute to freeze at that altitude….

3/14/1943

“Florence is in the next ward, an officer’s surgical, which is a different matter. There, one works. She has been taking care of a badly shot-up young pilot. It has been a heart-breaking job. I couldn’t have stood it one day. He screams out loud all the time. His nerves have gone…” (the patient died from his wounds on 3/23/1943)

04/30/1943

“We can’t imagine there even being a rumor of strikes. These boys that come pouring in smashed beyond repair, the wards full of blind boys, the huts of young fliers with amputated hands, they are American boys making $50 a month. What can strikers be thinking of? Some of these must be their boys too! It’s all beyond me. “

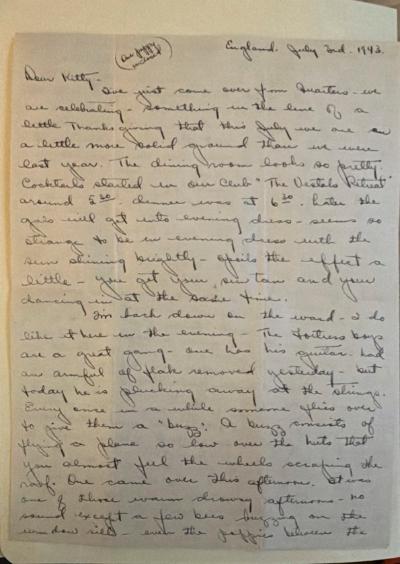

07/03/1943

“There is so much tragedy mixed with happiness here. A month ago Sammi Wing died. The same day Lulie Hampton was married to John Shaffer. Two days ago John’s plane was last seen going down over Germany with five fighters on his tail. He was a reconnaissance pilot. They fly small fast planes, go by themselves and depend on speed to get away. He wouldn’t stand a chance if it came to bailing out. Death doesn’t even make a ripple here. A phone call “John’s plane has not returned,” and life goes on as before.”

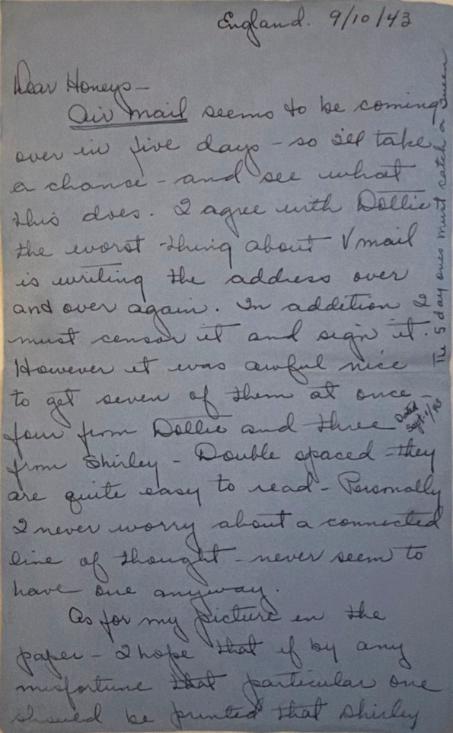

09/10/1943

“Something tells me England will be glad to settle down with her own families once again. There are so many homeless one wonders how they are ever going to get together again, families that have had to send the children away four years ago. Four years means so much in a child’s life. Fathers and sons gone for four years and no sign of any end to the war yet. People learn to count their happiness in hours, not years. Down by the Nissen hut wards the asters and French marigolds make a lovely splash of color. My little fat Fortress tail gunner told me he planted them. “I put these all around the barns at home. My cows like them.” Then he squatted down and looked up at me laughing and said, “Gee, Miss Hogan, I’d sure like to brin in just one more load of hay.” But his plane has not returned. The boys remarked when they heard, “…and he probably lent his parachute to the waist gunner!” There is so much comedy and tragedy mixed up in the day…

9/29/1943

…Of course, here they have collected all the paper, even asked for “love letters” to tide over the paper shortage. Everyone has given up everything in the clothing, furniture and dishware line to people who have been “bombed out” so that living is down to essentials, but everyone still has tea at 11 and 3:30 p.m.!...

11/1/1943

“We went visiting an English home where the piece de resistance was to be new potatoes boiled in their jackets fresh from the garden. It was a butterless day so we rather wondered. The table was set like a long buffet across a window overlooking the garden. The potatoes were served steaming hot in deep blue plates and on each plate was a pint-sized pitcher of well-thinned mayonnaise poured over them. I’ve never tasted anything so good. We ate everything in sight…You asked where we get the Scotch. We have a bar connected with our quarters. It is called the Vestal’s Retreat, opens at 7 p.m. The first dozen can have Scotch, after that it’s beer or cokes….”

11/21/1943

“…I sometimes wonder what it will be like after the war, at home, somewhere around ’47. So many seem to think they are going back to exactly the same world they left behind. I don’t see how it can be the same, ‘specially if we do our share of helping and rebuilding here. Suppose it might be a good idea to win the war first. Some of the boys who are returning home are aghast at the optimism there. Maybe it’s better that way, just as long as all realize that the worst and hardest pull is still ahead. There is much collecting from our Christmas boxes for the children in orphanages and ‘specially in the hospitals. There are so many children growing up in the hospitals since the blitzing. Boxes have been put up around the hospital and everyone is putting in one week’s ration of candy and cookies and anything they can spare from their Christmas boxes. Money, of course, is of no use because you cannot buy cookies or cake. Many of the boys save up their rations regularly and take them across the street to the Children’s Orthopedic Hospital…Time out for the news. There isn’t any. It’s just fight, fight, fight, Berlin, Russia, Beruit, Australia…”

11/28/1943

“Every once in a while a sentence in your letter makes me realize what a different world we are in over here. The store windows and the Christmas decorations! I can remember how lovely they always were. Here the windows are boarded and, of course, no decorations. The five and six year olds have never seen a Christmas decoration!”

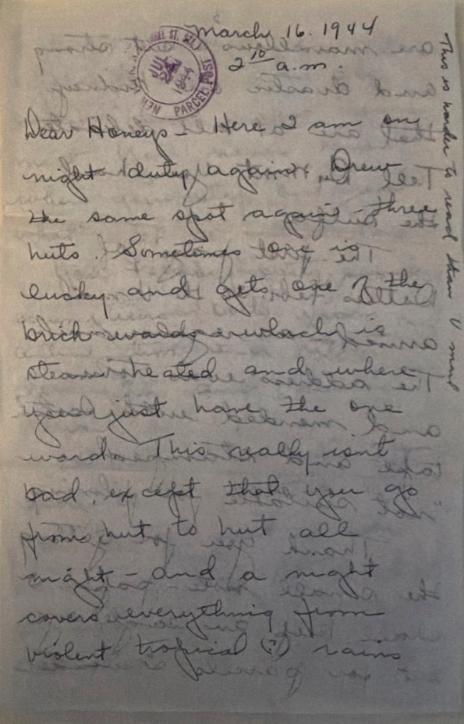

3/16/1944

…We carried away a jug of martinis from the bar and invited the corridor to a cocktail party. One of the girls had a package of potato chips and we set up a packing case desk with the blue paper napkins Kitty sent. …The olives were the piece de resistance as everyone always takes his martini with the remark, “-if we only had an olive.”…Tomorrow we are going over to the orphanage and take along a few things we’ve made. These are the children who were picked up as infants after the early London raids. No one has ever claimed them, probably all killed. When you think of all the plans their parents probably had for them.

7/30/1944

Did I ever complain about not being busy! We rolled up the beach. It was like the ‘shoot-the-shoots’ at Aylmer only instead of bathing suits, we were in full equipment. When we got into the landing boats we opened our harness belts and draped a “Mae West” around our necks, a needless precaution as the Royal Navy says they consider the English port more dangerous than this side on account of the flying bombs. As far as we were concerned, the trip was a pleasure jaunt except for the baggage. When we finally got altogether up the road and sat down for a breathing spell, one of the girls took off her helmet, fluffed up her curls, put a six-bowed purple velvet hair ribbon on top, got out her lipstick and went to work and we knew everything was under control. Since then we have been dumped bag and baggage in several fields where we proceeded to set up our tents and open K rations and picnic. The K rations are our pride and joy. A box the size of a cigar box comes in breakfast, dinner, and supper sets. The supper consists of biscuits, canned meat, cheese, boullion powder, a Nescafé (envelope), 1 teaspoon, 4 cigarettes, chocolate bar, chewing gum and toilet paper…We all think the toilet paper should be in the breakfast package! Our last move was to our permanent site and we went gaily off, decked out in pinks and baby breath (on our helmets) all packed in trucks like contented sardines. We arrived at the most beautiful spot, an apple orchard up on a hill. I couldn’t wait to unload so I climbed out over the side with much puffing and hanging on only to find a news cameraman grinding away. It will probably be shown in Seattle. Anyway, I was second over the side. Tents u, baggage rolled down, clothesline went up (we had to bring our wet laundry in our raincoat). Then we were issued 5-in-1 K rations and were so hungry and so tired that we sat down under the apples trees and open cans and gorged down everything cold. Then we sat back with a sigh of perfect peace. At this moment along comes our Chief with a list and, to my utter astonishment, I find myself in a team going to the Evacuation Hospital “Be ready in an hour,” so we threw all the wrong things into our hand bags folded up our beds and sped away! Here we are! I have never worked so hard in my life. I can’t call it nursing. The boys pour in, get emergency treatment, penicillin and sulfa and are shot out again. It is beyond words and the boys are such grand patients! By the end of the day we fill up our helmets with hot water, have a sponge bath, then wash our “little things” consisting of socks and undies in the same water and make ourselves a nice, hot cup of Nescafé (not in the same water! This is the most comfortable spot of the day and roll into our blankets. The night skies are beautiful, like the fireworks at the World’s Fair. We are not in any particular danger unless you count our own shells! Hospitals are sprouting up all over and soon the load will be lighter. In the meantime, everyone is doing a grand job, even the German prisoners who act as stretcher bearers all over the hospital, stand chow line with the boys and cheer their side in dogfights. I won’t be able to write individually so will you send this along. We have Mass every day for peace of mind of those at home as well as for the boys and peace in general, so do not have me praying unnecessarily!

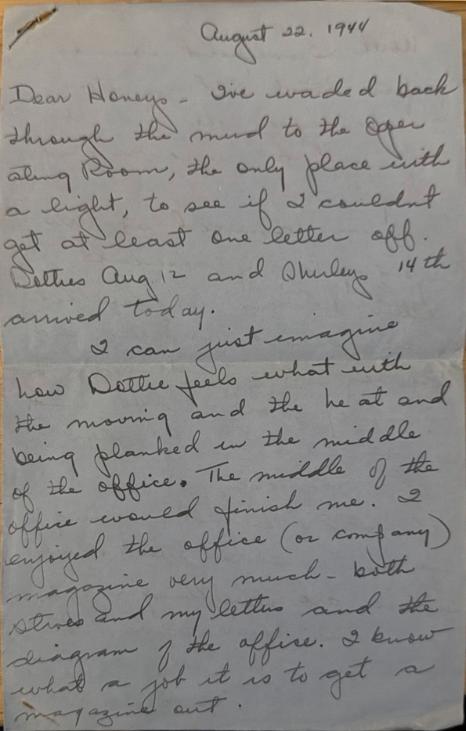

8/22/1944

I’ve waded back through the mud to the Operating Room, the only place left with a light, to see if I couldn’t get at least one letter off…I was amused at your referring to my “cheerful” letters. Heavens! Why shouldn’t I be. I have to arms and two legs, two good eyes, a family to go home to and a home in a country that is not a desolate waste, devastated beyond anything anyone can imagine. Our blockbusters are something I hope you never hear. I do not know how these people stand up against it. In the midst of it all you see two and three year old children. I have a young woman in the ward. The village was warned to take to the fields, but she couldn’t find one of the children and by the time she and her husband and five children got started so had our bombers. She saw her husband with the baby fall flat on the road, what has happened to the others she does not know. She was the only one advancing troops found. This is only one small incident. Compared to these people wea are as carefree as birds. We are now way back behind the lines in our own hospital. Working with the team at the forward Evac. Hospital was very exciting and satisfying but a heartrending job. No time for actual nursing, all emergency and first aid work, plasma, transfusions, penicillin. We hope that maybe we will get these boys back here and be able to give them all the extras they deserve…Every crossroad is crisscrossed with signs of different outfits…Food here is welcome. Our mess is good but we are always hungry for something different. There are no stores, no shops, no canteens, nothing!...There is nothing here. No fruits, no produce, no people except very small children, very old men and women, a few cows and millions of wasps and an awful odor. The war is going so rapidly that all may be changed tomorrow or next week.

09/05/1944

…To live in peace, to be with congenial people, to have joy in one’s work, to have one’s most loved ones near, I would hesitate to ask for more. Life is so cheap in war. The wite [SIC] crosses are packed so close in the field after field. When I think I probably have 15 or 20 more years in which to live, they somehow seem quite precious and I’m suddenly anxious not to waste any of it in looking back or making too many plans for the future. The war news is good. Maybe it is near the end. I hate the word “liberated”. Blasted off the face of the earth would be nearer the truth. The men are all out picking up the native brand of French. They have taken to answering us in French on the ward, but their accent is so American that it is not hard to understand. All day I hear German spoken and translate from my little book, so Heaven only knows what language I’ll speak on arriving home…

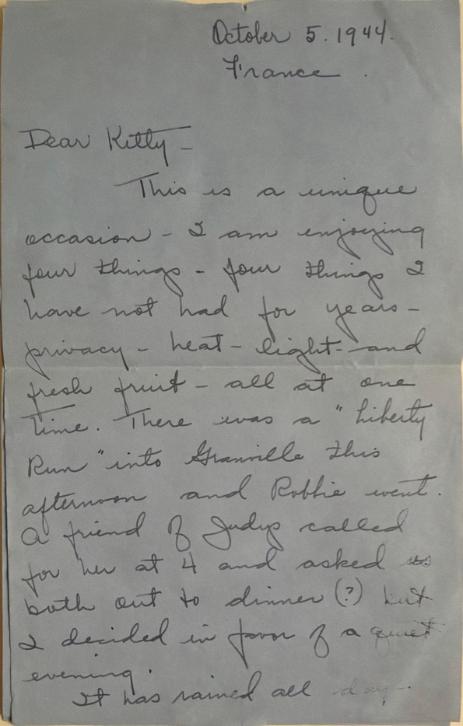

10/05/1944

…We are having a lull in work. We have cleared out several blocks and are waiting for hospital trains, our or P.W.s, no one knows. I, personally, feel that if they are P.W.s it means our casualties are slight. Anyway, a sick man is a man to be nursed back to health, regardless of race, creed, color or nationality, though harboring such sentiments makes people such as Skippy feel that I am collaborationist. Human kindness and charity is strangely missing in so many places. If we cannot show the Nazi that we have a better way of life and that we are better people because of it, I can’t see why we fight. Sometimes I wish you were with me so much that it hurts. Other times I am glad you are far away from it all.

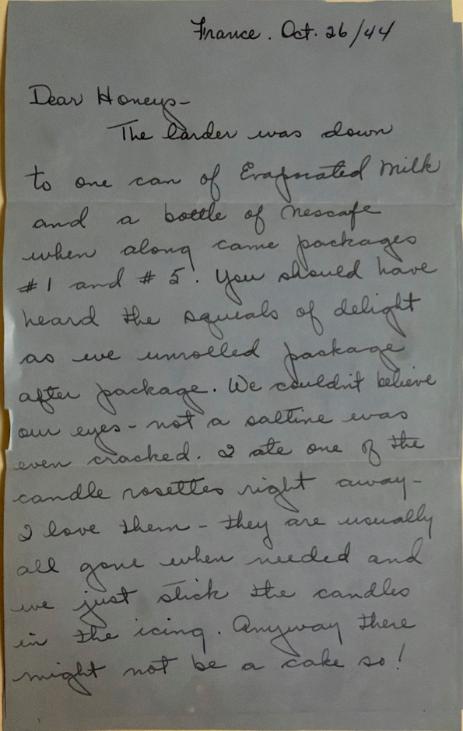

10/26/1944

…We are using peat blocks for fuel. They burn up too fast. Getting fuel is evidently going to be quite a problem. The Coal has to be hauled in from the beach in bags and I guess the loading and unloading reduces it to the consistency of fine sand. There is probably bootlegging of coal as well as gasoline. Too bad the bootleggers couldn’t be put up in the front lines with the infantry boys for a day or so. Let them see what a lack of supplies could mean. The news of the naval with the Japs is good. The boys back from the lines are not optimistic regarding a quick finish, but we can always hope. We have an outfit fresh from the States in the field across the way. We’ve quite a time. “Mined to the hedges” is a joke to them. They cross fields, leap over hedges. It took a tragedy to bring them to their senses. A little French boy in the field next to theirs found a shell and was carrying one home across the field when he stepped on a mine. The other outfit brought him into the hospital and believe me they keep to the roads and demined fields now!

12/31/1944

…To me the most tragic boys are the ones who crack up under the nervous tension. They are often the bravest of the brave. They have gone in Africa and Sicily, they have fought across France and one day their nervous system will take no more. There is no way to recognize a too taut nervous system. This soldier collapses and too often goes home marked “neuroses” to a family who think he is a shirker and not able to stay up on his own two feet when in reality he is as sick or sicker than the man with a physical wound or the nurse who goes home with chronically acute sinuses…

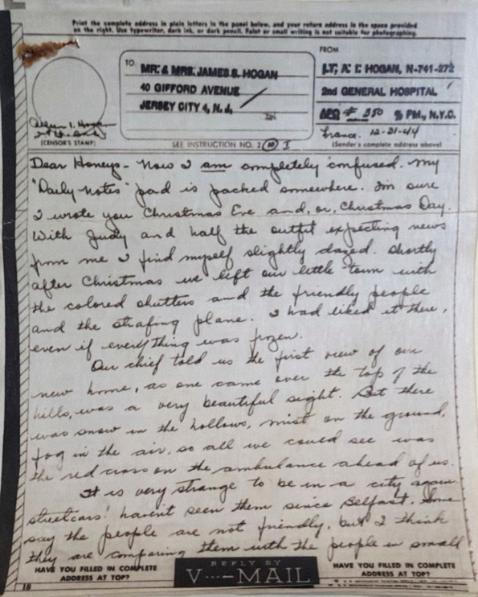

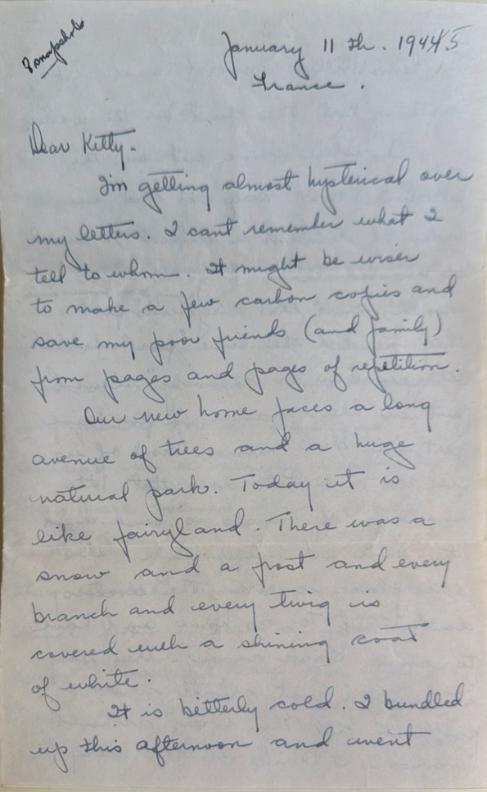

01/11/1945

Personally, I think the country should be on a total war basis. Maybe Congress is doing this now that elections are over. Two things are fairly the job of the home front: 1. To see that the Army has the equipment with which to fight and what a lot of ground that covers. Our P.W.s told us that the ground we are paying for so dearly for now was evacuated by them way back in September, but that they came back and reinforced it when they found we had not the gas to go further. 2. To see that the wounded man returning gets care and understanding and equipment to become self-supporting again. I have seen England working on a total war basis. Take a family such as Mae’s. From your letters there is a mother, capable and well, a sister who has skillful willing hands, Mae herself is young and healthy. In England, the grandmother, if under 65, would be at war work. Also the grandfather, if under 70. Both girls over 18 would bin the Forces. Mae would be given a month before and six weeks after her baby was born. She would then return to war work. The family would be allowed to arrange their shifts at work so that someone was always at home with the baby. It’s marvelous how babies thrive on a little wholesome neglect. I have seen young English pilots, paralyzed from the waist down, sitting in wheelchairs looking after six babies while their mothers were at war work..We are up against a young, tough, beautifully disciplined army. Behind it is a home front where even the six-year-olds carry hand grenades and know where to place them. Their young women are fighting in tanks side by side with their men. Believe me, a woman defending her home, has no vestige of mercy or kindness in her heart for the enemy.

2/-/1945

I have never been so tired in my life. I think it is because we have lost so many patients and so needlessly. We have had a steady stream of boys coming in who have had methyl alcohol in their cognac. They only live a few hours and those who do survive are blind. We put up such a fight to save them but so far it has been almost futile. Some of the boys have been over as long as we have, have fought through all the campaigns, have been sent to this city for rest, have a glass of cognac with their dinner and it is fini!

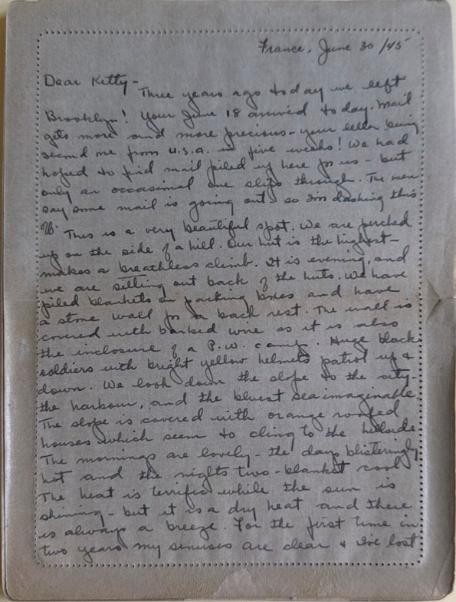

6/30/1945

“Kitty, I hope my changing does not make you restless or leave you feeling that I do not want to go home. More than anything in the world I want be a civilian in a world where all my friends are civilians too. I am sick to death of war and fighting and ruins and armies. But the war is not over and I have not the courage to go home and have to say goodbye again and have to start all over.

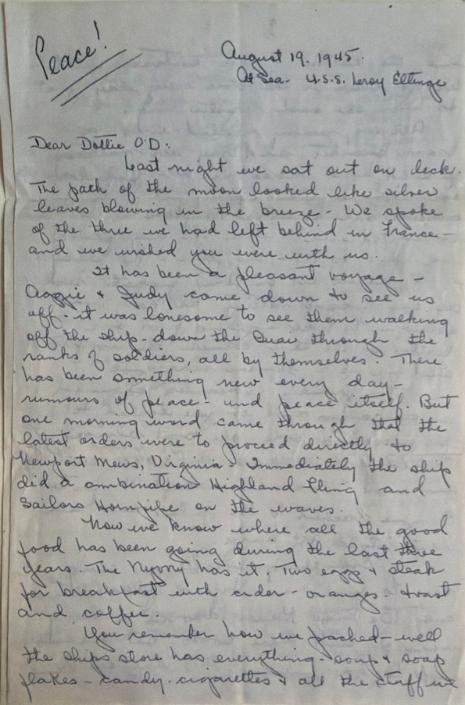

8/19/1945

The change of plans has been so sudden that quite a few have not been able to make the adjustment and are worrying over the future. Some are quite disappointed not to be coming in to N.Y.C. as they have never seen the Statue of Liberty. I’ve told them it is usually too foggy to see anyway. Apart from those few gripes, everyone is happy. Our future is anyone’s guess. 48 hours at the port, then to reception center nearest home. 48 hours there and then off on a 30-day “overseas” leave, then back to the reception center to learn our fate.

[1] The transcript of the same letter includes a note provided upon review by Ms. Hogan sometime after the war. “Upon arrival to Liverpool, a group was hurriedly assembled to go to Ireland where a hepatitis epidemic was occurring. Unfortunately, the disease was unknown to the medical men at the time. The true cause was not uncovered until a year later. The soldiers were from the unit that was to invade part of North Africa….They went from 200 to 90 pounds in a few weeks. The cause was laid to “mass hysteria” and most were invalided back to the U.S., some were given psychiatric discharges…”

[2] For more information regarding the Polish 1st Armored Division please see Polish at Heart.