Spinning a Yarn: Weaving the Story of Textile Arts at Teachers College

This blog post is in support of Filaments of Learning on exhibit in the Offit Gallery, and the display in the curiosity cabinets, Textiles in Learning and Teaching.

To Stitch and Sew: Textile Arts at the New York College for the Training of Teachers

In the fall of 1889, the New York College for the Training of Teachers bustled with activity. It was the opening semester for the newly founded college, and its classrooms at 9 University Place brimmed with aspiring educators, ready to learn from professionals in their fields. Building upon the philosophies of the Kitchen Garden Association and the Industrial Education Association, the New York College for the Training of Teachers served as a professional school for teachers and aimed to reinforce vocational education and manual training as part of school curricula [1]. The College offered bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in pedagogy and students enrolled in the department of domestic economy (what we might recognize today as home economics or family and consumer sciences), set out to learn educational theory and practice and to solidify their practical skills in cooking or sewing [2]. The program’s instructors included Julia Hawks Oakley, professor of domestic economy; Emily Augusta Oakley, instructor of sewing; Julia Locke Bedford, Minette De MaCarty, and Annie Louise Jessup as special instructors in sewing; and Elizabeth Anna Buchanan, Caroline Hope Roberts, Charlotte Allen Sherwood, and Jennie Chatterton as special instructors in domestic economy [3].

The department of domestic economy’s sewing course was the first program to incorporate textile arts into the college’s curricula. The program, according to the 1889 Circular of Information, “aim[ed] to give a thorough training in plain hand-sewing, to cultivate precision, and through the medium of object lessons, to impart a knowledge of textile fabrics and their manufacture, and other articles used in sewing”[4]. The sewing program taught aspiring domestic economy educators methods for teaching sewing, embroidery, and weaving in kindergartens, grammar schools, and high schools [5]. The students also had access to the college’s model school, where they could observe the teaching techniques employed in manual and industrial arts classrooms. Under the supervision of sewing instructors and other professors in the department of domestic economy, students like Maude Cooper, Lydia Taber Robinson, and Hattie Alexander Russell learned about educational science, elementary and secondary pedagogy, and the instruction of textile arts [6]. While the only record of their enrollment in the department’s sewing course is in the pages of the 1889 Circular, an 1891 model sewing book from the college found in the Gottesman Libraries’ archives is indicative of Maude, Lydia, and Hattie’s work within the program [7]

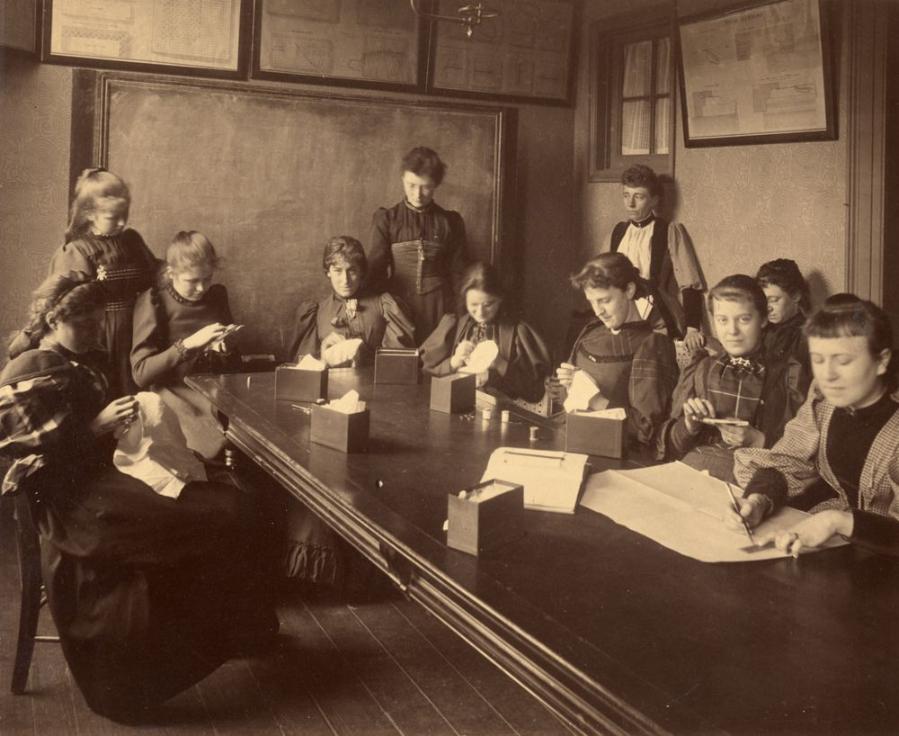

Sewing Class. At The Upper Left Sits Myra Kelly, Future Author Of Little Citizens; And Behind Her Stands Anne George, Daughter Of Henry George, Now Mrs. William DeMille. 9 University Place. Teachers College. (Date Not Known) TCANA: Historical Photographs of Teachers College.

The model sewing book documents the work completed by students in the model school’s primary course in sewing. This course was observed, and at times supervised and taught by, students with a concentration in domestic economy. The models in the sewing book demonstrate “the various kindergarten occupations of sewing, cutting, folding and weaving”[8]. The primary course was designed to help instructors prepare children ages 7 to 9 for more difficult needlework learned in the upper grades and to teach students the basic skills required for work in the textile or garment industries. The primary course outline included suggestions for teachers, urging they employ object lessons in how to use cotton and linen as well as how to use thimbles, how to thread and use sewing needles, how to make knots, and how to use scissors [9]. The sewing book includes models for cutting, sewing, embroidery, and other stitching techniques, with instructions for using and making patterns, how to choose fabric, and how to select thread. It contains original samples of students’ embroidery as well as sample stitches for use in garment construction. The model sewing book’s embroidery examples evidence the ways students employed color, shape, line, and texture with embroidery floss and needles. Floral and botanical embroideries are common features throughout the model sewing book, demonstrating steady hands and artistic sensibility, while indicating the students’ expected level of skill.

Embroidery example from the 1891 model sewing book (MG 120), featuring a blue floral or palmette design with gold border and embellishments. The design is embroidered on linen.

For the students in the domestic economy course at the New York College for the Training of Teachers, vocational skills, fine and domestic arts, and scientific approaches to teaching and learning were deeply intertwined. Within the sewing book, model embroideries and stitching patterns are mounted on the pages like pressed flower and fern specimens in herbaria. Instructions accompanying each model outline potential avenues for students to explore a broad range of subjects. Several of the sewing models and accompanying exercises instruct students to pencil sketch simple objects or letters onto muslin to practice different stitches. The model sewing book suggests students draw and then stitch a “star, a triangle, or circle, or fruit [such] as an apple, pear, etc., [such] as a single flower or leaf” [10]. These exercises allowed students to improve their manual dexterity and artistic skills through needlework, while also inviting discussions about academic subjects such as geometry or botany. In this way, the sewing course, designed by women working in vocational education, was an interdisciplinary, multi-modal approach to learning.

This kind of approach continued and expanded when the college drafted a new charter, changed its name to Teachers College, and became affiliated with Columbia University at the close of 1892 [11]. This new iteration of the college required an invigoration of fresh ideas to keep pace with increasing enrollment and shifting educational philosophies. With the college’s updated charter came new course offerings as well as departmental transformations. The department of domestic economy became the department of domestic science and art, and within this department Mary Schenck Woolman began her tenure at Teachers College, infusing practical skills, educational science, and theories about child development into the domestic science and art curriculum [12].

Mary Schenck Woolman, the Power of the Sampler, and the School of Practical Arts

Mary Schenck Woolman began her work in the department of domestic art and science as a departmental assistant in 1892 [13]. She was quickly promoted, becoming an associate professor and director of domestic art in 1897, a full professor in 1903, and an advisor to students concentrating on the teaching of domestic art in 1907 [14]. During her twenty-year career at Teachers College, she taught over fifty courses, including courses on teaching sewing and needlework methods in elementary, secondary, and women’s trade schools; courses in household art and design; courses on historical, economic, and scientific aspects of textiles and clothing, as well as courses that infused discussions of textile arts with educational psychology, pedagogical theory, child development studies, and the history of education [15]. The structure, content, and methods of Woolman’s textile courses largely drew from her foundational 1892 book Sewing Course for Schools: With Models & Directions as to Stitches, Materials & Methods [16]. Grounded in Froebel’s Pedagogies of the Kindergarten, Woolman’s Sewing Course argues for an approach to sewing education that is rooted in student’s natural interests, asserting that “the child must not be sacrificed to the model, or … by the demand of the teacher for over-accurate work” [17]. Instead, she posits that children can learn problem-solving, develop fine motor skills, and enhance critical thinking through “self-activity” [18]. In this sense, sewing and textile arts are means to cultivate children’s aesthetic and moral sensibilities as well as their sense of community and social responsibility. Woolman saw textile arts as serving “strong sociological, economical and ethical” functions, impelling educators and school administrators to incorporate textiles into the teaching of other subjects [19]. “The way things are made” she writes, “is often of intense interest to the children, and the teacher can easily make their history and manufacture part of geography, history, mathematics, etc.” [20]. Textiles, and their subsequent material, cultural, historical, and economic valences were then important aspects of a holistic education. Textile arts, such as sewing and weaving, were not just vehicles for learning valuable trade skills, they were modes of artistic expression, and avenues for understanding the connection between material culture and academic disciplines.

Example of model 13, small drawstring bag, from Woolman’s Sewing Course. The bag is plaid, with alternating black, tan, and red stripes over a cream fabric.

Mary Woolman’s Sewing Course established the pedagogical basis for how textile arts were taught at Teachers College during her tenure. At least ten courses, including, “Domestic Art 1-2: Handwork — Sewing for the Grammar Grades” list the book as a required text [21]. Woolman and her colleagues’ classes infused mathematics into the study of textile consumption and trade; surveyed scientific approaches for identifying fibers, dyes, and cleaning solutions; considered the artistic principles of textile design; explored historic and current craft practices; and debated the ethics surrounding shopping and dress [22]. These strands of inquiry and practice were woven into the work undertaken by students and other instructors within the department. Students researched problems in the field, such as how to implement textile arts programs into schools and suggesting how a textile-based curricula could support social and intellectual development. In her master’s thesis, Uses of Textiles in Public Instruction in the South, 1910 graduate Stella Palmer, for example, addressed the lack of a comprehensive textile arts program in Alabama and explored how textile courses could address young girls’ social needs [23].

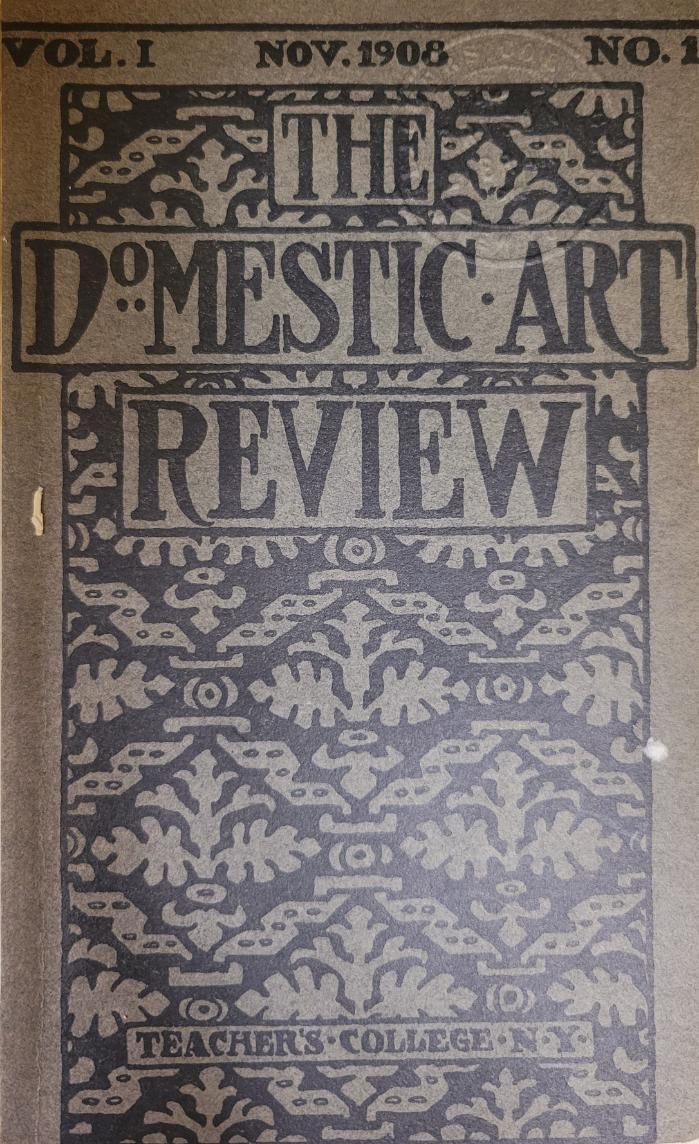

Under the direction of Mary Schenck Woolman, Anna M. Cooley, and other instructors such as Elizabeth Sage, undergraduate and graduate students founded a journal devoted to the domestic arts. The inaugural issue of The Domestic Arts Review (later The Household Arts Review) was published in November 1908 by members of the Domestic Arts League, a Teachers College student organization dedicated to the study and practice of domestic arts. The Review aimed to connect educators and students, provide guidance for practitioners, and record the department’s scholarly output [24]. Student and alumnae articles and editorials on the topic of textiles from each issue are rich and varied. “Oriental Rugs,” by Helen B. Brooks supplies a historical and technical overview of Turkish and Persian rug-making while also contextualizing the cultural importance of spinning, weaving, and dyeing practices as they related to decoration and ornament [25]. “The Wardrobe of A Girl at Teachers College” by Bessie White explores how a domestic art student could plan her wardrobe on a budget, noting the kind of fabrics and materials needed for constructing garments. White’s article lists fabric and trimming options for morning dresses, shirtwaists, skirts, and hats, offering insight into the complicated wardrobes of early 20th century women [26]. Her suggested outfits consist of corsets and undergarments, corset covers, petticoats, stockings, skirts or day dresses, shirtwaists, vests, jabots or neck ties, overcoats, gloves, hats, shoes, dressing gowns and various accessories. White’s editorial reveals that domestic art students had to be skilled in clothing construction as well as clothing economy.

Front cover of the inaugural issue of The Domestic Art Review. The cover design was inspired by textile samples in the collection of fine arts professor Arthur Wesley Dow.

Later articles in the Household Arts Review included an editorial by alumna Charlotte A. Waite titled, “Need for Legislation Regarding Textiles.” Waite’s article focuses on tariffs and regulations in the wool trade and explores how such legislation could either empower or alienate women in the textile industry by affecting their purchasing power [27]. The final textile-related article in the journal’s run was the work of student Jennie E. Kelly. Kelly’s “Sewing and Self-Expression” recalls Woolman’s Sewing Course, contending that sewing is not just an avenue for teaching practical skills, but that it is tool for “developing the character of [the] student” [28]. Sewing exercises, Kelly maintains, demonstrate students’ “care and skill” as well as “the desire to produce something worthwhile” [29]. For Kelly, a lace-making exercise could reveal students’ artistic sensibilities as well as their attitudes toward their work. How students approached a given exercise could demonstrate a sense of individuality or a desire to conform to a set standard [30]. Kelly’s article ultimately concludes with a discussion of the domestic art teacher, arguing that to foster students’ practical and mental abilities, teachers need to have strong character, deft practical skills, vivid imagination, and a charismatic yet commanding voice [31]. These student articles evidence the ways economics, educational methodologies, history, and cultural analysis were integrated into the domestic arts curriculum at Teachers College and demonstrate the interdisciplinary approach to textiles present in Woolman and her colleagues’ teaching.

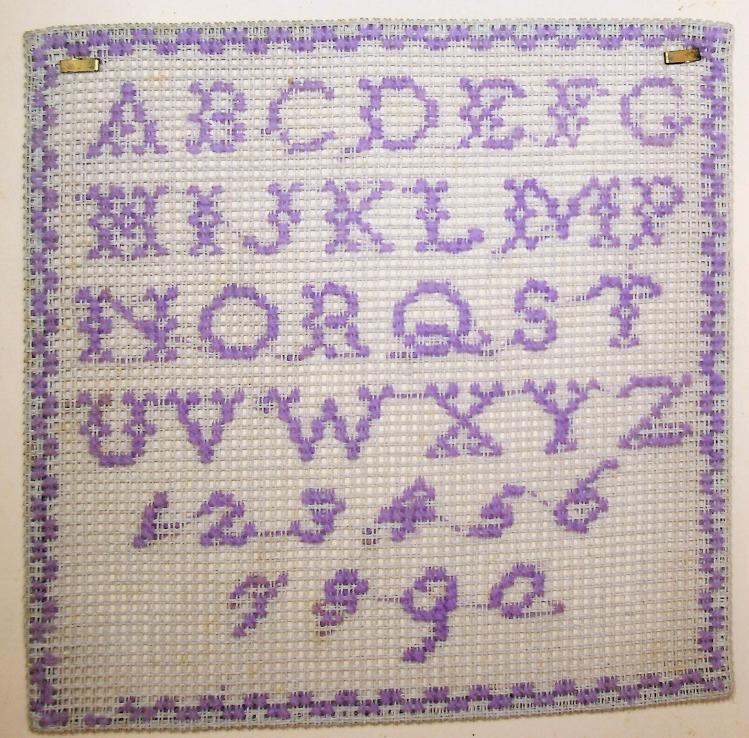

Woolman’s own articles in the Household Arts Review expound upon these ideas and demonstrate the importance of textile arts in women’s education. Her article in the February 1910 issue, “Sewing – A History of Education,” outlines the importance of sewing, knitting, and crochet in girls’ education and contextualizes needlework and other handicrafts within educational history. Woolman evaluates how textile arts historically afforded American and European girls with an educational outlet, as eighteenth century schools often excluded them from learning “the three R’s” [32]. Woolman equates samplers’ instructional value to the hornbook, framing them as important artifacts of women’s learning and craft [33]. Through needlework, Woolman contends, young girls learned “the alphabet, numerals, ethics, and other subjects” [34]. Her article ends by discussing the founding of domestic arts programs devoted to handwork and manual training, as well as the establishment of trade schools for impoverished and immigrant women by philanthropists like Emily Huntington and Grace Dodge [35]. Woolman argues that Teachers College was founded as a direct result of their philanthropic of work, affirming the importance of domestic art and textile arts within the institution and setting Teachers College apart as a leader in the field. Woolman’s colleagues, including Anna M. Cooley, Laura I. Baldt, and Florence Winchell all contributed articles to the Review which focused on textile arts and textile economics, and Professor Paul Monroe even wrote an article discussing the history of industrial education and manual arts, demonstrating the importance of textile arts in Teachers College’s legacy.

Example of a sampler from Woolman’s Sewing Course.

Under professor Mary Schenck Woolman’s direction, the domestic science and art program flourished and grew. As of November 1909, over 200 students were registered in the program [36]. The existence of disparate concentrations, such as textiles and needlework, foods and cookery, and hospital administration, alongside and the increasing student enrollment in the program necessitated change. By 1910, the college had constructed a new building to house the division while also unifying nursing, cooking, textile arts, household design, and chemistry courses under one department: the department of household arts and sciences [37]. The new building for household arts and sciences, Grace Dodge Hall, included laboratories and studios replete with a “student work room … furnished with work tables, sewing machines, and other needed equipment” that afforded students the opportunity to continue their practice outside of class hours [38]. The fifth floor held a textile laboratory that included a loom as well as equipment “for dyeing and apparatus for chemical and microscopical tests of textiles” [39]. In the studio spaces were examples from the Teachers College textile collection, which included textiles from the medieval and Renaissance fabrics as as well as examples of American and European lace-making and embroidery [40]. Dr. Denman W. Ross of Harvard and Professor Arthur Wesley Dow, head of the fine arts department at Teachers College, loaned pieces from their own private textile collections for student study. These combined collections included examples of Italian silk and lace; Spanish and French damasks and brocades; embroidery from China, Japan, and India; Turkish linen and embroidery; Tapa cloth from Hawaii; and palm-fiber rugs from the Congo [41]. The dedicated work spaces, laboratories, and historic textile samples available for student use all attest to the importance of textile arts in Teachers College’s history and highlight the pedagogical focus on multi-modal and interdisciplinary learning. Mary Woolman’s tenure saw textile courses combine mathematics and science with principles of artistic design and cultural history. By the time she resigned from Teachers College in 1912 to to head the home economics department at Simmons College, much had changed in the department.

Textile Exhibit in Grace Dodge Hall circa 1909, Historical Photographs of Teachers College.

Design and Science in Textile Arts: The Pedagogy of Jane Fales

After Mary Schenck Woolman resigned from Teachers College, professor Jane Fales served as head of the textile arts concentration within the department of household arts. Fales graduated from Teachers College’s in 1907 and began teaching in the department 1909 [42]. She taught courses on dressmaking, textile analysis, dress and costume design, and costume history, with her publications similarly centering textile design and costume arts [43]. Alongside fine arts professors Arthur Wesley Dow and Ruth Wilmot, Fales also served as an advisor for students concentrating in costume design. Her tenure at Teachers College, her publications, her course descriptions, and a notebook belonging to one of her students, demonstrate the way Fales ushered in a new understanding of textile arts as an academic discipline.

Under Fales’s direction, the department of household arts and sciences began to more clearly distinguish between textile arts and textile sciences. This distinction is apparent in the course catalogs, where textile courses were no longer listed under the general heading of “household arts,” but under the course headings of “clothing” and “textiles” [44]. Clothing courses focused on the artistic aspects of sewing, embroidery, and dress design whereas textile courses focused on the economic, historical, chemical, and molecular analysis of textiles [45]. Through these course title distinctions, Fales aimed for aspiring textile artists and household arts educators to gain a more holistic understanding of textiles. She hoped such distinctions would allow for a more rigorous study of the artistry in textile arts, not only in students’ grasp of design principles, but in their understanding of textiles as material culture, textiles’ aesthetic value, and textiles’ economic, social, and historical importance [46]. Fales felt that each aspect of textile arts and sciences should be “studied by themselves … in separate sequence” with “one common purpose in mind, that of increased increased skill in proper expression” [47]. For Fales, the ideal household arts program would gradually build up a students’ knowledge of textiles, hone their artistic and constructive techniques, and instill a strong appreciation for the “rules of design” [48]. She wanted students to graduate with more than expert sewing skills; she wanted to ingrain in them design expertise, an appreciation for textiles’ social and economic importance, and an acute grasp of the methods used to identify quality fibers for use in weaving, embroidery, or sewing.

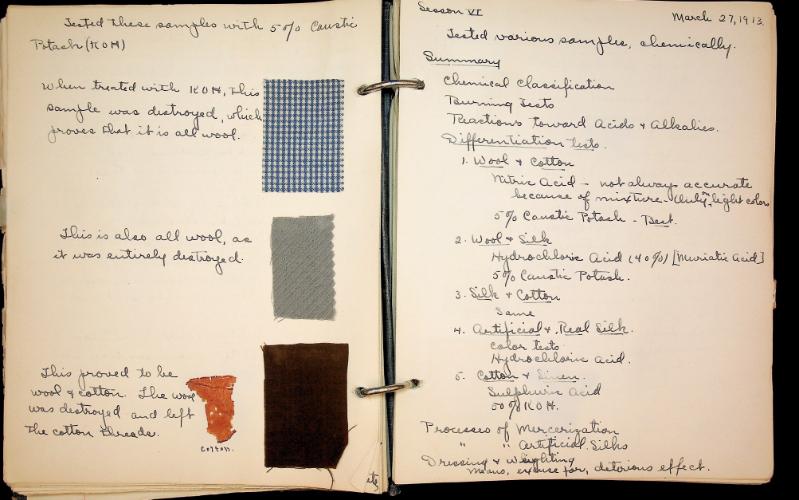

An extant example of Fales’s pedagogical approach can be seen in the notebook of one of her students, Dorothea Donnan, which is held in the library’s archives [49]. Donnan, an alumna of the class of 1914, was enrolled in Fales’s course, Textiles 31, in the spring of 1913. Dorothea Donnan’s meticulous notes document how Jane Fales’s course built a strong foundational knowledge of textiles by covering a broad sampling of topics. The course traced the history of textile arts, concentrating on women’s role in the development of the craft and industry; it outlined various methods for textile design and manufacture, such as spinning, weaving, and dyeing techniques; it discussed the material, social, and economic importance of textiles; and it provided frameworks for grading textiles and analyzing the chemical and molecular components of cotton, linen, wool, and other fibers [50]. Donnan’s notebook contains detailed outlines for each lecture, experiment, and assigned readings, including Loom and Spindle, or, Life Among the Early Mill Girls and the Teachers College technical education bulletin, “The Determination of Cotton and Linen by Physical, Chemical and Microscopic Methods” [51]. Donnan recorded guest lectures given by Ellen Beers McGowan, professor of household chemistry, demonstrating Fales’s dedication to highlighting practitioner expertise. The notebook illustrates Fales’s interdisciplinary approach to textiles, documenting how she attempted to provide a foundation on which to build practical skills and knowledge for teachers and practitioners of textile arts.

RG 29: Dorothea Donnan Notebook, Textiles 31, Spring 1913. The above notebook pages outline chemical tests Donnan conducted in Fales’s class, wherein she treated fabric samples and studied their reactions to identify their base fibers.

While Dorothea Donnan’s notebook evidences Fales’s commitment to teaching the scientific, historical, and economic aspects of textiles, the course catalogs and Fales’s own writing make manifest her devotion to the study of textiles as a fine art. For Fales, dress and costume design were as much about pattern-making, draping, and sewing as they were about illustration, composition, and proportion [52]. While she was a professor in the department of household arts and sciences, her service as an advisor to fine arts students concentrating in costume design put her in conversation with fine arts professors like Arthur Wesley Dow and Ruth Wilmot. In their costume courses, Fales and Wilmot drew on Dow’s art education treatise, Composition: A Series of Exercises Selected from a New System of Art Education. Employing Dow’s philosophies, Fales and Wilmot furnished students with foundational examples of textile design and costume illustration, educating “the student in appreciation of good lines and spacing, dark and light, [and] color” while also providing students with opportunities for self-expression in illustrating and constructing their own garments [53]. Fales’ collaboration with Wilmot displays the overlap between household arts and fine arts courses at Teachers College and considers how textile arts could sit within the fine arts discipline.

Jane Fales resigned from the household arts and science department 1921 to head the department of costume economics at Margaret Morrison Carnegie College [54]. Her tenure at the college set a precedent for the future of textile arts and sciences at the college. In the coming decades, the department of household arts would concentrate more on textile science and clothing economics while the fine arts department would become home to courses in costume design, textile design and weaving, substantiating Fales’s belief that textile arts were an art in their own right. The next women to take up Fales’s work included student of Arthur Wesley Dow and Ruth Wilmot, Belle Northrup, and Fales’s fellow clothing and textiles instructors, Laura Irene Baldt and Lillian Locke.

Textile Economies and Textiles in the Arts

Belle Northrup’s Approach to Costume Design

Throughout the 1920s, the department of household arts and sciences and the department of fine arts continued working to define the boundaries of textile arts and sciences. In the realm of fine arts, instructor Belle Northrup, endeavored to collapse the distinction between textiles as objects of craft and textiles as an art form, infusing fine arts and design principles into costume and clothing arts. Northrup graduated with a B.S. in fine arts in 1917 and began her teaching career as a departmental assistant that same year, supporting Ruth Wilmot’s costume arts courses and teaching a few courses of her own [55]. She served as an instructor in fine arts until 1931, when she earned her master’s degree, and from 1932 to 1945, Northrup was an assistant professor in costume design, stage design, and art education [56]. Her costume illustration and design courses drew from Jane Fales’s philosophy of textile art as fine art, combining Fales’s approach with Arthur Wesley Dow’s principles of art as a mode self-expression. Northrup’s 1927 article, “Teaching Costume Design for Independent Thinking and Creating” exemplifies her attempts to shift conceptions of textiles as functional and decorative objects to an understanding of textiles as emotionally resonant pieces of creative expression. She writes of costume design as a combination of art and craft, but emphasizes the “essential, creative elements in their relation to personality,” noting that costume design, illustration, and construction rely on a “capacity for development and vision” that draws from “the joys of color and form” [57]. In combining practical skill, psychology, and the principles of good design, costume artists could conceptualize wearable art. For Northrup, like Fales, knowledge in clothing construction and drawing alone weren’t enough to successfully design or create a garment; a deep appreciation for color and proportion were necessary to achieve the abstract and expressive elements of dress.

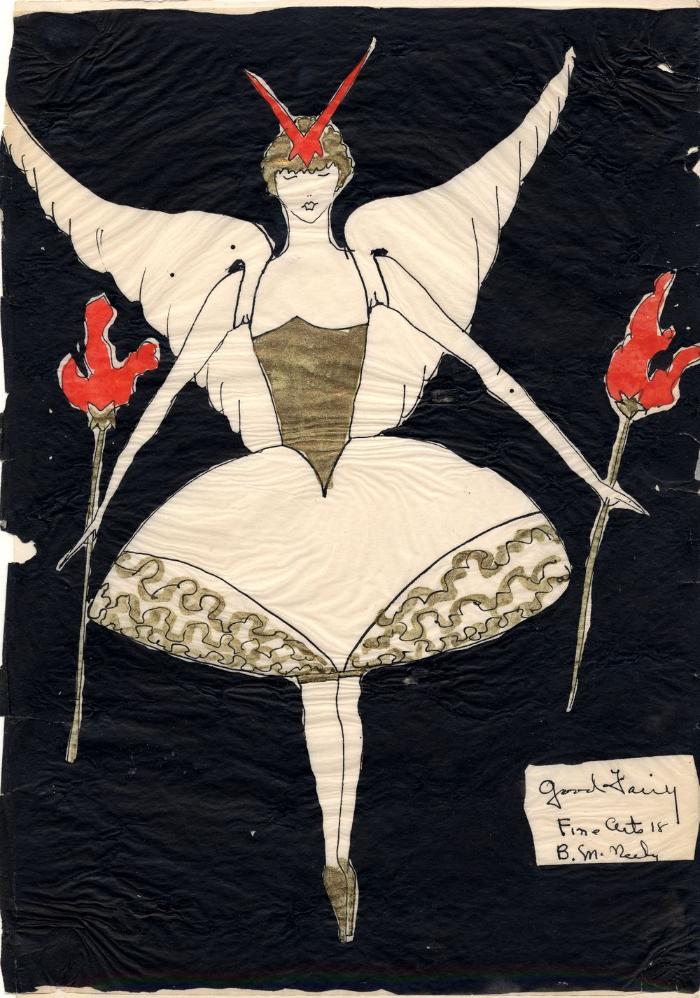

The drawings of one of Northrup’s students, Mary Elizabeth “Bessie” McNeeley illustrate the kind of work undertaken in her costume design, costume illustration, and stage design courses. Bessie McNeeley, class of 1923, was enrolled in Northrup’s course, Fine Arts 18 — Art for School Plays and Festivals, which explored “color harmonies and designs for stage settings and costumes” [58]. McNeeley’s work displays Northrup’s commitment to teaching the visual effects of line and color in dress and suggests how students in costume courses infused an individual sense of style and artistry into their work. McNeeley’s drawings feature designs that are at times delicate, at others playful and bold in their composition. Each drawing considers the position of the figure, the drape of the clothing, and the way color plays with shape. McNeeley’s work had practical application as well. The designs from Fine Arts 18 were used to create costumes for the annual Teachers College Festival, an event consisting of student-produced plays, concerts, dance performances, and faculty lectures [59].

“Good Fairy,” Art Group 1: McNeeley Costume Drawings. McNeeley’s illustration depicts a woman with white, feathered wings, dressed in a gold bodice, and white tutu-like skirt with gold trim. She wears gold shoes and holds fiery, long-stemmed torches in each hand. Her arms frame the shape of her tutu. She also wears a red v-shaped headpiece that sits on top of her golden hair.

Northrup continued to teach costume arts throughout the 1920s, 30s, and 40s, as well as courses in art appreciation, fine arts design, and arts and craft. Her courses, such as Fine Arts 222 — Advanced Costume Design, taught students the ins and outs of color theory, familiarized them with dyeing techniques, educated them on textile patterns and materials for use in clothing, and built for them a foundation in the principles of design [60]. Her course, Fine Arts 221 – Problems in Teaching Costume Art, explored art structure, psychology, and pedagogical methods for teaching costume design [61], and her art appreciation course, Fine Arts 119a – Art in daily living, encouraged students to see the beauty in everyday decorative objects and to use real world examples as inspiration for creating striking designs [62].

Clothing Economies and Textiles as an Industry: the Rise of Home Economics at Teachers College

Parallel to Belle Northrup’s work in the department of fine arts, Laura Baldt, Mary Evans, and Lillian Locke focused on the practical skills and disciplinary knowledge needed to understand textiles and clothing within the context of household arts. With Laura Baldt heading the clothing and textile concentration at the start of 1922, courses became increasingly oriented toward textiles’ practical, chemical, and economic aspects. Laura Baldt’s courses covered dress construction, clothing selection, and pedagogical approaches to teaching textile arts and sciences. Throughout the 1920s, she lectured on the role of textiles in household furnishing and clothing, led demonstrations on the technical skills required for dressmaking and tailoring, and instructed students in the teaching of clothing and textiles in high schools and colleges [63]. Her fellow instructors, Lillian Locke and Mary Evans also offered courses on dress design and construction, dress appreciation, clothing consumption and economics, historical and current methods in clothing and textile manufacture, clothing and textiles for the family, and clothing reclamation, while Ellen Beers McGowan led courses on textile chemistry and analysis [64].

Dodge Hall. Class in Designing. Summer Session. Teachers College. (1920)

Evans and Locke’s course offerings especially demonstrate a more methodical and scientific approach to textiles. Throughout the 1920s and 30s, students enrolled in the department learned techniques for constructing and repairing clothing, methods for identifying fabric and fibers, and ways to become conscious clothing consumers. To familiarize students with the labor and materials integral to the textile and clothing industries, Lillian Locke’s field studies courses saw students visit textile mills and garment factories [65]. Students enrolled in Mary Evans’ course, “Cultural backgrounds of textiles and clothing,” explored the historical foundations of modern dress, examined current problems in the textile industry, and discussed the social and economic aspects of clothing [66]. The focus of Evans and Locke’s courses indicate a larger shift in the field and in the industry, suggesting that that by the time the pair headed the department in 1931, textiles held more importance as part of consumer industry than as a home craft or artistic practice.

By 1942, the department of household arts had undergone another transformation, becoming the department of home economics [67]. The new program offered courses in home and family life, nutrition, consumer science, and clothing. Under this new disciplinary construction, textile-based courses included Clothing 100: Fundamental Problems of Clothing Construction; Clothing 175: Field Studies in textiles and clothing; Clothing 200: Technics involved in home furnishing and clothing reclamation; Clothing 225: Economics of Clothing Consumption; Clothing 245: Dress design; Clothing 250: Clothing construction for advanced students; Clothing 255: Fitting and pattern study, and Textiles 220: Consumer problems in textiles. While Clothing 200 saw students study the clothing and furnishing construction, dyeing and reconditioning techniques, alteration methods, and the fundamentals of hand loom weaving, it also was through the lens of textile technologies that students understood sewing, textile production, and garment construction. When the department of home economics underwent another disciplinary re-imagining and renaming in 1955 as the department of home and family life, clothing courses still remained, but they were reconstituted to serve the department’s focus on family psychology, consumer sociology and psychology as it related to clothing, and the chemistry of textiles [68]. With a new focus on family and child psychology, the department no longer saw fit to include a clothing or textiles concentration, but continued to offer clothing-related courses until 1967, when the last cohort of undergraduate students received their degrees [69]. Although home economics, and later home and family life, focused more on practical skill, clothing science, consumer science, and family psychology, textile arts were not cast out of the college’s curricula. It was in the department of fine arts that textile arts found a new home and a new understanding.

Textiles Arts and Arts in Craft: Textiles and Art Education

While costume design was offered in the fine arts department in some capacity since 1913, other fine arts courses considering textile arts were not offered until 1938. Outside of costume art, the first fine arts courses to incorporate textiles included Fine Arts 119a – Art in Daily Living; Fine Arts 167-168 – Art Appreciation; Fine Arts 101T – Principles of art structure; and Fine Arts 231-232 – Creative Design [70]. Fine Arts 119a explored the design of everyday objects, giving students vocabulary for understanding decorative and functional objects as products of intentional design. In Fine Arts 167-168, students learned and discussed problems, application, and topics in art appreciation, including how art functioned in the home and in society by examining architecture, textiles, dress, and decorative design [71]. In Fine Arts 101T, students learned the “underlying principles of design studied through the experiences of designing textiles, tiles, plates, pottery shapes, lamps, posters” [72]. In Fine Arts 231-232 students practiced design principles and techniques for use in art industries, including making designs for printed silks, cottons, cretonnes and wall papers [73]. These courses, taught by Belle Northrup and Sallie B. Tannahill, introduced fine arts undergraduates to fundamental principles of design and instilled an appreciation for handicrafts as art forms. By 1941, the department not only offered courses in textile design, it also offered textiles craft classes, initiating fine arts students into the tactile and expressive practices inherent in the medium.

Two Women Tapestry Weaving. Pearl Greenberg Collection.

These craft-related courses included Fine Arts 124 – Arts and Crafts, with a specific focus in textile arts in section 124c, and Fine Arts 188 – Weaving. Fine Arts 124c saw students practice and study “block printing, embroidery, appliqué, needlework, [and] simple weaving,” alongside methods and materials for use in teaching [74]. In Fine Arts 188, first taught by Belle Northrup, students attended interactive workshops that emphasized “design and experimentation” [75]. After studying and analyzing examples of textile patterns and their origins, students were encouraged to make small pieces on warp and thread looms, such as bags and scarves [76]. By 1946, a course dedicated to textile design was also offered in the department. Fine Arts 346 – Textile Design, taught design principles for textiles and techniques for printing, including block printing, silk-screen, batik, and tie-dyeing [77]. Throughout the 1940s, Elise Ruffini taught textile craft, design, and weaving courses, with other instructors, such as Lili Blumenau, Ella Odorfer, and Signe Ortiz taking charge of these courses by the end of the decade and into the 1950s. Various courses in costume art, textile design, and weaving continued to be taught in the fine arts department throughout the 1950s and early 1960s. By 1967, costume arts courses were no longer listed in the catalog, perhaps coinciding with Teachers College’s transition from an undergraduate and graduate school of education and vocational skills to a graduate school for education, psychology, and the health professions. Similarly, weaving courses disappeared from the catalog around this time, but textile design courses continued to include lessons on spinning, hand-weaving, and crochet [78].

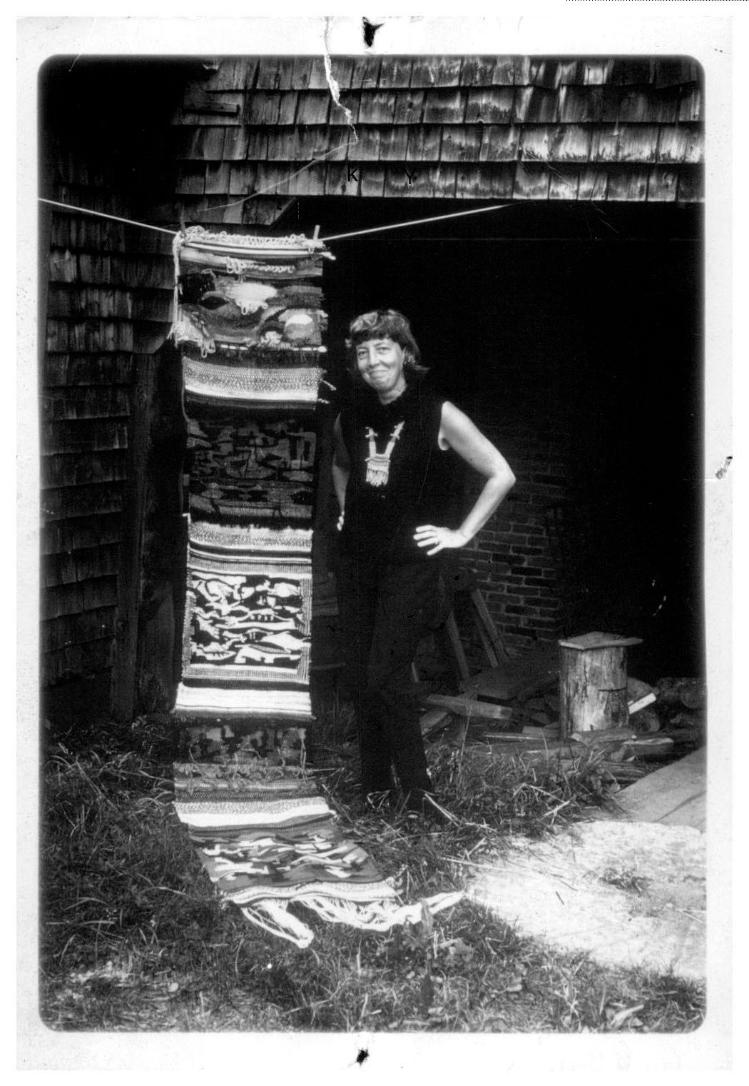

.While weaving courses were not offered in art and education department after 1967, student work still addressed the importance of weaving in the art education curriculum. Pearl Greenberg’s dissertation, Tapestry Weaving in the Art Education Curriculum (1971), suggests ways to incorporate tapestry weaving as an integral part of art education. She contextualizes weaving as a historical practice, highlighting the material components of weaving and outlining important terms and techniques for educators and students. She proposes tapestry weaving as a way for students to develop creative techniques and design principles, as for Greenberg, tapestry weaving could stimulate new and imaginative avenues for creative expression in students, offering unique visual and tactile ways to communicate ideas, emotions, and experiences [79]. She contends that art curriculum should follow student interests, allowing children to create their own working styles and rhythms and encouraging other art educators to let children play with materials in unexpected ways [80]. Similar to Mary Schenck Woolman, Greenberg discusses the ways such a curriculum could develop students’ fine motor skills, instill in them an interest in craft and historical practices, or encourage their curiosity about textiles in everyday life [81]. Greenberg strongly argues for a more serious approach to tapestry weaving in art education. She notes that weaving should not be taught in passing, or only when students appear ready; it should be introduced as part of a comprehensive art education program [82]. Pearl Greenberg went on to become an influential artist and educator, working as a fine arts instructor at Kean College for almost 30 years. She was also recognized as a distinguished fellow in the National Art Education Association and was one of the founders of the University Council for Art Education.

Pearl Greenberg with tapestry. Pearl Greenberg Collection.

After Greenberg graduated in 1970, the art and education department began offering other textile related courses, including T5260 Experiments in content; crafts, fibers taught by Caroline Von Kleek-Beard and TT4240: Fibers and Fabrics taught by Carol D. Westfall [83]. Von Kleek-Beard’s course focused on fiber construction using off-loom techniques, while Westfall’s course surveyed “techniques used in fabric embellishment and fiber manipulation,” including off-loom weaving and dyeing techniques [84]. A variation of these courses continued to be offered until the spring of 1989, when the last textile-based course was taught in the department, which by then called the arts in education [85]. Dissertations like Carmel Mary Murtagh’s and Paulette Renee Young’s show that there was a sustained interest in textiles as aristic, cultural, and historical practices even after the decline of textile arts within the Teachers College curriculum. Even today students, faculty, and staff demonstrate the ways the legacy of textiles at Teachers College continued to evolve.

Textile Arts at TC Today

Since 2023, the Gottesman Libraries has exibited textile-based artwork from staff and students, continuing to give space to the legacy of textile arts at Teachers College. In 2023, Lisa Daehlin, academic secretary in international and transcultural studies at Teachers College, exhibited her show “Crochet Mandalas and Stories of the Heart” in the Offit Gallery on the library’s third floor. Her crocheted mandalas played with geometric shape and line and used expressive color and imagery to connect people. In 2024, Carina Maye, doctoral student in the art and art education program at Teachers College exhibited her show in the Offit Gallery, “Let Me Think About It.” Maye’s exhibit featured five abstract mixed-media tapestries that touched on “individual identity, symbolism, and reflective learning with familial artifacts.” This upcoming spring, Jennifer Ruth Hoyden, doctoral student in the art and art education program, will exhibit her rug hooking practice in the Gottesman Libraries’ Offit Gallery. Hoyden’s work, “How long does it take to hook a rug?” was also featured in the Macy Gallery’s September Primer (2025). In a real-time demonstration of artistic action, Hoyden used ribbons of wool to hook lines in her rug. Her rug hooking practice serves as a document of her time and labor and asks us to consider the materials and tools used to create the rug. While textile arts are not part of the curriculum at Teachers College, interest in textiles’ tactile, material, and expressive qualities remain. Women have carried on this legacy of arts and craft for nearly 140 year, demonstrating the value of ancient artistic practice and skilled labor across time.

Carina Maye’s tapestry reflecting on the theme of love. Digital Capture From the Digital Futures Institute.

Woven into the fabric of Teachers College’s history is the legacy of women’s contributions to education though textile arts. If we view this history as a woven tapestry, then in the archives and special collections, we can trace the weft threads of domestic art and fine art curricula as they cross the warp threads of progressive pedagogy, interdisciplinary learning, and humanitarian concerns. In the samplers embroidered by the students at the New York College for the Training of Teachers; in the sewing course designed by Teachers College’s Director of Domestic Arts, Mary Schenck Woolman; in historic course catalogs; in The Domestic Art Review published by the department of household arts and sciences; in the notebook of Dorothea W. Donnan, a student majoring in textiles and clothing; in costume drawings; in master’s theses and doctoral dissertations; in exhibitions, we can see the artistic output, intellectual curiosity, and material engagement of students and instructors past. By examining these archival traces, we can follow the threads and reveal one of the many ways women have shaped Teachers College, explore attitudes towards the fine arts and arts in craft over time, and trace changing ideas about the role of art in education.

References

[1] New York College for the Training of Teachers, Circular of Information (New York College for the Training of Teachers, 1889), 11; Lawrence A. Cremin, Mary E. Townsend, and David A. Shannon, A History of Teachers College, Columbia University (Columbia University Press, 1954) 17.

[2] Circular, 10; 25.

[3] Circular,4-7.

[4] Circular, 25.

[5] Circular, 25.

[6] Circular, 40 & 44.

[7] Sewing Book — Models with Instructions Used by The College for the Training of Teachers New York (1891), Manuscript Group (MG) 120, Home Economics Samplers, Gottesman Libraries Special Collections and Archives, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, N.Y. The sewing book was gifted to the library by the late Professor Anna M. Cooley, instructor in the department of Household Arts.

[8] MG 120, “Primary Course,” 1.

[9] Ibid.

[10] MG 120, “Model #1.”

[11] Teachers College, Columbia University, Teachers College Circular Of Information 1893-94*(Teachers College, 1893) 7.

[12] Cooley, Anna M.,“Biographical Material on Mary Schenck Woolman,” Record Group 28: Anna M. Cooley Papers, 1940, 5. Gottesman Libraries , Teachers College, Columbia University.

[13] Cooley, “Biographical Material on Mary Schenck Woolman,” 4; Teachers College, Columbia University, Teachers College Circular Of Information 1893-94 (Teachers College, 1893) 6.

[14] See Anna M. Cooley’s “Biographical Material on Mary Schenck Woolman” (5) and the following circulars/ announcements for a list of Woolman’s titles: Circular of Information, 1894-1895; Circular of Information, 1897-1899; Teachers College Announcement, 1898-1899; Teachers College Announcement, 1902-1903; Teachers College Announcement, 1903-1904; Teachers College Announcement, 1905-1906; Teachers College Announcement, 1907-1908; Teachers College Announcement, 1910-1911; and Teachers College Announcement, 1911-1912.

[15] See the above TC circulars and announcements for a full list of Woolman’s courses. See also Anna M. Cooley’s “Biographical Material on Mary Schenck Woolman” for a discussion of Woolman’s approach to domestic art and pedagogical theory (5; 15).

[16] The college commissioned Woolman to write A Sewing Course, which was subsequently revised and republished a number of times: in 1900: A Sewing Course: With Models and Directions as to Stitches, Materials, and Methods; in 1905: A Sewing Course for Teachers : With Models and Directions as to Stitches, Materials and Methods; *and again in 1910: *A Sewing Course for Teachers, Comprising Directions for Making the Various Stitches and Instruction in Methods of Teaching. A Sewing Course was also used as a textbook for textile and clothing courses into the 1910s. See 1910-1915 Announcements for more.

[17] Woolman, Mary Schenck. A Sewing Course for Teachers : With Models and Directions as to Stitches, Materials and Methods (The University Bookstore, 1900) 7.

[18] Woolman, A Sewing Course, 7.

[19] Woolman, A Sewing Course, 1.

[20] Woolman, A Sewing Course, 1 & 7.

[21] Columbia University Teachers College Dean’s Report (Columbia University, 1907) 75.

[22] Woolman, Mary Schenck, “Textiles and the Curriculum,”The Household Arts Review, vol. IV, no. 1 (November 1911): 3.

[23] Palmer, Stella, *Uses of Textiles in Public Instruction in the South* (Teachers College, Columbia University, 1910) 1.

[24] Domestic Art Review, vol. 1, no. 1 (November 1908).

[25] Brooks, Helen B., “Oriental Rugs,” Domestic Art Review, vol. III, no. 3 (April 1909): 15-25.

[26] White, Bessie, “The Wardrobe of A Girl at Teachers College,” The Household Arts Review, vol II., no. 3, (April 1910): 47- 49.

[27] Waite, Charlotte A. “Need for Legislation Regarding Textiles” The Household Arts Review, vol. IV, no. 1, (November 1911): 27.

[28] Kelly, Jennie E. “Sewing and Self-Expression,” The Household Arts Review, vol. VI, no. 2 (March, 1914): 32.

[29] Kelly, “Sewing and Self-Expression,” 32.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid., 33 & 35.

[32] Woolman, Mary Schenck, “Sewing – A History of Education,” The Household Arts Review vol. II, no. 2 (February 1910): 9.

[33] Ibid, 10.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Andrews, Benjamin R. “School of Household Arts and Sciences,” The Domestic Art Review, vol. II, no. 1 (November 1909): 23.

[37] Ibid, 22.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid., 23.

[41] Ibid., 24.

[42] Teachers College Announcement 1911-1912 (Teachers College, Columbia University 1911), 15.

[43] See Teachers College Announcement 1911-1912, Teachers College School Of Education Announcement 1913-1914, and Teachers College School Of Education Announcement 1918-1919 for examples of Fales’s courses.

[44] See Teachers College Announcement 1911-1912, 103 for the first instance of the distinction between “clothing” courses and “textiles” courses.

[45] See Teachers College School Of Education School Of Practical Arts Announcement 1915-1916, 74 (187 in PDF).

[46] Fales, Jane, “Design as the Keynote in Courses in Textiles and Clothing,” Teachers College Record 16 (1915): 265-268, https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811501600305.

[47] Fales, “Design as the Keynote in Courses in Textiles and Clothing,” 266-267.

[48] Ibid., 267.

[49] Notebook kept by Dorothea Donnan for Textiles 31 Course (1913), RG 29.881215, Box 1 of 1, Record Group 29: Students, Dorothea Donnan Notebook, Gottesman Libraries Special Collections and Archives, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, New York.

[50] RG 29: Dorothea Donnan Notebook.

[51] Herzog, Alois & Ellen A. Beers, “The Determination of Cotton and Linen by Physical, Chemical and Microscopic Methods,” Teachers College, Columbia University Technical Education Bulletin, no. 7 (no date). A copy of the bulletin is bound into Donna’s notebook (RG 29).

[52] Fales, Jane, and Ruth Wilmot, “A Course in Costume Design,” Teachers College Record 17 (1916): 263 https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811601700314.

[53] Fales & Wilmot, “A Course in Costume Design,” 265. See also Teachers College School Of Education Announcement 1917-1918, 67 (p. 199 in PDF).

[54] Correspondence between James Earl Russell and Jane Fales (1919-1922), RG 6. 790727, Box 13, Folder 217, “Fales, Jane,” James Earl Russell Papers, Series 4: Correspondence with the Faculty, Gottesman Libraries Special Collections and Archives, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, New York.

[55] Teachers College School Of Education Announcement 1917-1918, 67 (p. 199 in PDF).

[56] Belle Northrup Faculty File (1958), RG 17. 861006, Box 33, Folder, “Belle Northrup,” Record Group 17: Office of Public Relations: Faculty Files, Gottesman Libraries Special Collections and Archives, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, New York.

[57] Northrup, Belle, “Teaching Costume Design for Independent Thinking and Creating,” Teachers College Record, vol. 28, no. 7 (1927): 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146812702800704.

[58]Teachers College School Of Education Announcement 1922-1923 (Teachers College, 1922), 49 (232 in PDF).

[59] Ibid.

[60] Announcement Of Teachers College School Of Education School Of Practical Arts 1929-1930, 159 [194 in PDF].

[61] Announcement of Teachers College, Columbia University. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University (1938), 184.

[62] Ibid., 62.

[63] See the following Teachers College Announcements for a fuller list of Baldt’s courses: 1922-1923, 1923-1924, 1924-1925, 1925-1926, 1926-1927, 1927-1928, 1928-1928, 1929-1930, and 1930-1931.

[64] See the course catalogs from 1922-1955 for a full list of Evans, Locke, and McGowan’s courses.

[65] See Announcement Of Teachers College School Of Education School Of Practical Arts 1931-1932, 219 in PDF and Announcement Of Teachers College School Of Education School Of Practical Arts 1932-1933, 237 in PDF.

[66] See Announcement of Teachers College School of Education, School of Practical Arts 1938-1939, 195.

[67] Announcement of Teachers College School of Education, School of Practical Arts 1941-1942.

[68] Announcement Of Teachers College Winter And Spring Sessions 1954-1955.

[69] Autumn And Spring Terms Teachers College 1966-1967.

[70] See Announcement of Teachers College School of Education, School of Practical Arts 1938-1939, 181-184.

[71] Ibid., 182.

[72] Ibid., 182.

[73] Ibid., 183.

[74] Announcement of Teachers College School of Education, School of Practical Arts 1941-1942, 167-168.

[75] Ibid., 168.

[76] Announcement Of Teachers College 1945-1946, 113 (148 in PDF).

[77] Announcement Of Teachers College 1945-1946.

[78] Teachers College Autumn And Spring Terms 1972-1973, 150, (172 in PDF).

[79] Greenberg, Pearl, Tapestry Weaving in the Art Education Curriculum (Teachers College, Columbia University, 1971) 133.

[80] Ibid., 137.

[81] Ibid., 138.

[82] Ibid., 158. For more on Pearl Greenberg’s writing and work connected to textiles and weaving, see the Pearl Greenberg Collection.

[83] See Teachers College Autumn And Spring Terms 1975-1976, 149 and Teachers College Autumn And Spring Terms 1976-1977, 147.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Teachers College Autumn Spring And Summer Terms 1989-1990.